One of my first memories of Ada Limón involves a party in Brooklyn nearly 15 years ago. Ada was across the room, in a beautiful blue coat. A mutual friend introduced us, whispering as she did that “her poems are even lovelier than her coat is.” Within months, I knew this to be true.

One of my first memories of Ada Limón involves a party in Brooklyn nearly 15 years ago. Ada was across the room, in a beautiful blue coat. A mutual friend introduced us, whispering as she did that “her poems are even lovelier than her coat is.” Within months, I knew this to be true.

I am lucky to know Ada: We moved in similar circles in New York in our twenties, and left about the same time. I came home to California, and she moved to Kentucky, while still keeping her ties to Sonoma, her hometown, active with regular trips. (She has read at Flight of Poets, a series I host with Hollie Hardy in Sonoma.)

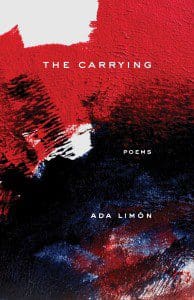

Over the decades, Limón’s work has honed a deft music against her gift for trapdoor syntax, where suddenly a verse drops us into a plush red heart or clambers out of itself to see the sky. Her poems have also gained tautness and emotional resonance, in particular in her haunting, fiery collection Bright Dead Things, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Limón’s fifth book, The Carrying (120 pages; Milkweed), offers a new chapter in an already beautiful and accomplished oeuvre.

As ever, Limón’s poems keep lighting up the rooms they enter. In response to her fifth book, Ada and I corresponded over the month of September about travel, tenderness, and new work.

ZYZZYVA: I’m catching you on a weekend when you are traveling: let me start with a question about travel and home. We in California are happy to claim you as a Californian, but you live in Kentucky now. As you travel a lot these days between homes or former homes— Kentucky, Sonoma, New York— does the travel affect your writing? Is there any place that feels “more” like home now?

Ada Limón: It’s fitting that I am answering this question on a plane. I spend a lot of time on a plane these days. I’m leaving California and heading back to Kentucky, trading one home for another, if you will. I don’t mind traveling. I get a lot of writing and reading done on planes and trains. Also, I’ll admit, I’m with my dog (who is under the seat and currently holding on to my feet) and my husband. This is my favorite way to travel—with my family. Sonoma still feels like home to me. I still have my small apartment on Moon Mountain (which miraculously survived the fire). My mom and stepdad still live in Sonoma. My father, stepmom, and big brother all live in California, too. It feels like I belong to that land, like I’m a native bird of the Valley of the Moon. But Kentucky feels like home to me, too. We have our house there and our two old cats, and I’ve written the majority of my last two books there. I’m a bit more isolated in Kentucky in some ways and I think that actually can help my writing. Sonoma brings out some nostalgic poems and Lexington brings out some more present “of the moment” poems. But they do both still feel like home to me.

Z: Yes, you have many homes, as it were. And: this is your fifth book! That’s a lot of poems, an oeuvre, even. To me you’ve been someone whose work I’ve admired since, say, Sharks in the Rivers— and before. How do you feel your writing has changed— both as you’ve written more and as your national stature has grown?

AL: Thanks for your kind words, Tess. To be honest, the “national stature” is pretty bizarre. The only way that I can think about it is to remember that it’s not about me, it’s about the work. I think, “Look what my poems have done!” as opposed to thinking the attention is on me. Of course, I came home to Poets & Writers –– with a picture of me on the cover –– just late last night, and Lucas proudly put it on the table. I had to bury it under other magazines so I could walk around the house freely. It’s not that I don’t appreciate that generous attention, it’s just that it makes me nervous somehow. Mainly, it means I travel more, give more readings, and so forth.

I wrote The Carrying largely thinking of it as poems for me, for my intimate friends and family. After the kind attention Bright Dead Things received, I wanted to write something that excavated my own personal demons and didn’t hold back, while still focusing on sound and image. Then, suddenly I realized the book was larger than me and I started to think of it as something that might be read beyond my inner circle. So, on some level I hope that any manner of attention –– good or bad –– hasn’t changed my work. But time has changed it. Space has changed it. Life has changed it too.

Z: I love what you say about staying utterly focused on the poems, less on the big distractions of poetry business. I think that’s wise. I’m thinking about the early magic of your work — the lovely trapdoors you make language take, such as lines in this current book like: “ Some days there is a violent sister inside me, and a red ladder/ that wants to go elsewhere.” Talk to me about magic and also where lines like that come from.

AL: I don’t know if I find lines or if I hear them moving around in me and catch them. That line came from the phrase “violent sister”; I had been thinking of those words and how they sounded together. The hard sounds of “violent’ paired with the hissing sounds of “sister” made my mouth feel alive. So that line began with sound and then formed into a meditation. The idea that we have someone inside of us that wants to get out, break the barn doors and go free. I suppose we all have her. Sometimes my lines begin with sounds before I even can make sense of the phrasing or syntax. I love when that happens because it makes the poem-making almost feel more like song-making.

Z: Yes, we do get caught in words. Or: they catch us. A word I noticed in your book, a number of times, was “tender”, or “tenderness.” As in “uncupping our ears to hear/ the song the tenderest animals made.” Or in the poem called “Against Belonging”: “I’ve named them / so no one is tempted to kill them (a way of offering/ reprieve, tenderness).” Talk to me about tenderness.

AL: It’s interesting you mention that, I keep thinking of that word and how it’s something I’ve been using a lot lately. I love that you notice those things. You and your good ear. I wrote The Carrying at a time when I was trying to be tender to myself and also to the world. At that time (which is also now), the world felt so brutal and so full of hate, I wanted to remember tenderness. To release a vulnerability or skinlessness that allowed me to be freer in my work. When I am suffering in any way (from illness, physical pain, or emotional baggage), I tend to move toward a hardness and a closed-offed-ness and a self preservation that often doesn’t even allow for breath. These poems were me trying to find that breath again, to be soft to the world again.

Z: Ada, I feel this conversation is helping me breathe better as well. I’ve been thinking a lot about carrying, too. Right now, in this terrible moment, I know that this sadness and anger is a weight I keep shouldering. Right after the election it felt so heavy. I don’t know how to carry this, I’d say. Didn’t know how to shift it actually through and in the body, so that I could get on with — well, anything. I am not less angry but I feel a bit more practiced in carrying some of its heft. I love that line in your poem about carrying grief.

How has it felt to you, in these past years, making space for the poems? I talked about fame or having a lot of books, but how has, say, the starkness of this moment shifted your writing? Or conversely, not shifted it?

AL: I think the election just sent us all reeling—even those of us who knew the underlying hate was there all along. In some ways that admission, the overt hate, the fully exposed racism and bigotry and lack of care of our environment was a great reveal. It exposed what was always there. It was almost a relief not to have to convince people that America was divided anymore. I don’t know if my work shifted, but I think that I see things more clearly in general. I am also better at setting boundaries for myself (still working on this), so that I am making sure I am taking care of myself. I think self-care is a radical act for every one, but especially for women and for women of color. I think, during this tumultuous time, I am learning mostly how to allow for gratitude and rage to live inside of me at the same time. I acknowledge that they both have a purpose, but I also know that I can’t live in rage all the time. No one can. It’s self-destruction. It’s fire. So this book and these new poems I was writing were a way of seeing both the fire and the good green life all at once, and letting those two things find a harmony—a harmony called survival.

Z: We need to strike that balance, certainly. I was thinking about it this weekend, when I was offline hiking here in California — just really away for the first time in a while. I was thinking about this odd balance of needing to stay vigilant and needing to renew; sometimes all in the same hour, the same day, the same body, the same poem. But here’s my nerdy confession: sometimes I read a lot of really classic stuff as my form of escape. I just finished the Emily Wilson translation of The Odyssey with Bennett, and on a whim, on this long hike, Taylor and I reread Midsummer Night’s Dream — partly because we were hiking through these enchanted groves up here.

Anyway — The Odyssey was great. Midsummer Night’s Dream was so much sillier than I remembered, and parts of it felt oddly wooden, though it does have this lovely little part about how all these things—our loves, our little fantasies, our dreams themselves—are snatched from us so quickly, before we recognize them. The mortal frailty of all our stories. The old lyric theme. “So quick bright things come to confusion” was the line that caught me. And, of course, I thought of Bright Dead Things—hearing an echo, a similar verbal glitter. It made me wonder: who are you reading? Who that’s alive, who that’s dead? What are your sources of inspiration and solace these days?

AL: I love that you read the classics. You know, I was a theater major and one of my favorite classes was the Shakespeare class. I am that total nerd who legitimately loves Shakespeare. I have a good friend, Corey Stoll, the actor, and he and his wife and I can spend a long time gushing about how excellent the musicality of Shakespeare’s lines are. I love reading the classics because you have that opportunity to say things like, “You know Virginia Woolf was really good,” but I also admit that I’m gushing a lot these days about contemporary writers, too. Maybe because there’s the diversity there that makes me feel seen. One of my confessions is that while I’m deep in writing a poetry a book, I can’t seem to read poems. I am such a mimic, it can be dangerous. So I tend to read novels. I love Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, Hannah Pittard’s Visible Empire.

Poetry-wise, I just devoured José Oliveras’s Citizen Illegal, Katie Ford’s If You Have to Go, DaMaris Hill’s A Bound Woman is a Dangerous Thing, Victoria Chang’s Barbie Chang, Terrance Hayes’s American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, and Erika Meitner’s Holy Moly Carry Me.

Z: Ah! So I wasn’t wrong, perhaps—quick bright things, bright dead things! And, yes, as I was reading the new translation of The Odyssey, I kept saying “This is so good!”—still half-surprised that it was, and also feeling deeply in awe, though, of course, lasting nearly 3,000 years has to speak for something. Still, those 3,000 years have been so radically imperfect in terms of who has gotten to speak and why, as you say.

I’m grateful to be a critic and poet and reader in this moment — many of those books you mention are favorites of mine, too. I feel there’s this beautiful generation we’ve gotten to be part of and a generation coming up who is knocking my socks off. I mean, the political world feels pretty hard right now, but the wide open future of poetry gives me hope every day.

Z: Can I ask again about influences—who was formative? Whose work do you find rattling around in your inner ear? Who do you love and maybe also argue with?

AL: To be honest, that’s my least favorite question in interviews. I don’t know why. I really push against it. I mean, it’s a great question and you are right to ask it, but part of me feels like it’s not for me to say. A reader might see some influences in my work and some that I might not even be aware of. I think my problem is that it feels limiting. I feel like I should just open up my arms and point to the sky and say “This!” But, of course, I’m sure my work was influenced. By my teachers, for one: Philip Levine, Marie Howe, Mark Doty, Sharon Olds, Galway Kinnell, and Colleen McElroy. And then the first poems and poets I loved: Elizabeth Bishop, Pablo Neruda, Lucille Clifton, Gwendolyn Brooks, Muriel Rukeyser. But I don’t have anything singular rattling around in my brain—it always changes. I think a lot about music, too. I think I’m as influenced by music and silence sometimes as I am by words. It’s funny, though: I love all these writers and artists, but I can’t compare to them or even be in the same context as them. They aren’t as much influences as benevolent guides I am so utterly grateful for.

Z: Ah, indeed: the big this. And you’re right — here I am hearing a kind of faint Shakespearean echo that may or may not be there, when maybe you never meant it. Poets are fish, swimming through the waters of language. Actually, did you know the human ear is evolved from the gill? That we are sifting air for sound the same way fish sift water for oxygen? I think the poet in anyone would love that. I love your gratitude too.

My final question, then, is about advice — for those people swimming this long, strange swim. Here you are at the fifth book. What’s your advice for those just starting out, and also for those who are doing the risky and hard work of continuing?

AL: Oh yes, the ear and the gill linked forever. I love that. I think I would tell people that in order to keep the work interesting, you have to keep writing poems that scare you. You have to keep pushing the limits and asking yourself the big questions. And it’s not just about the subject, but also about the making. I want to make things that matter. I want them to matter in terms of sound and matter in terms of emotional truth, but I want them to matter in a way that changes me. I write to be changed. I write to grow and become better at being in the world. Everyone is different, of course, but I start by making something that means something to me on a larger level. I steady my breath and jump all the way in. It’s the only way I know how to do this.

Tess Taylor is the author of The Forage House (Red Hen Press), a finalist for The Believer Poetry Award, and Work & Days (Red Hen Press), which was named one of the 10 best books of poetry of 2016 by the New York Times. Her third book, Rift Zone, is due out in 2020.