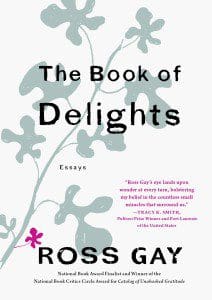

Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights (288 pages; Algonquin Books) is a collection of over 100 short essays. The project began as a type of writing exercise: Gay would write one essay about something delightful every day for a year. While the collection doesn’t contain an essay for every single day of that year, and some of the essays might be called more thought-provoking than purely delightful, the book couldn’t be more aptly named. The pieces read at times like prose poetry or journal entries, and they cover a variety of topics, such as a single flower growing out of the sidewalk or two people carrying a bag together. The Book of Delights brings together aspects of poetry, nonfiction, cultural criticism, and memoir, while keeping with the interests of Gay’s previous works. Gay spoke to ZYZZYVA about some of the overlapping themes that emerged in The Book of Delights, as well as his writing process:

Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights (288 pages; Algonquin Books) is a collection of over 100 short essays. The project began as a type of writing exercise: Gay would write one essay about something delightful every day for a year. While the collection doesn’t contain an essay for every single day of that year, and some of the essays might be called more thought-provoking than purely delightful, the book couldn’t be more aptly named. The pieces read at times like prose poetry or journal entries, and they cover a variety of topics, such as a single flower growing out of the sidewalk or two people carrying a bag together. The Book of Delights brings together aspects of poetry, nonfiction, cultural criticism, and memoir, while keeping with the interests of Gay’s previous works. Gay spoke to ZYZZYVA about some of the overlapping themes that emerged in The Book of Delights, as well as his writing process:

ZYZZYVA: Some essays in The Book of Delights feel incredibly personal, almost more like journal entries than essays. When you wrote these, what audience did you imagine you were writing to?

Ross Gay: That’s such a good question. I mean, there’s a handful of things in terms of audience that I’ve realized over the years. One is that I’m writing to myself. I’m my first audience, and I’m writing to figure these things out and deepen my relationship to these things, and I’m writing to delight and surprise and confuse myself, too, so that’s the first thing. And then, I’m writing very much to the people whose work and lives I feel intertwined with or inseparable from. My dear friends, like Patrick Rosal, Ruth Ellen Kocher, Curtis Bauer, and all these people who I’m in a kind of writing community with…and my neighbors, too! The Book of Delights especially is so rooted in where I live. I’m writing for my neighbors and for other people who are reading the books I’m reading, and for people who are interested in art criticism, because in some ways I think this book is criticism. And I’ve realized I’m also really writing to my brother.

Z: Could you talk a bit about what it’s like for you to move from poetry to prose—or perhaps between poetry and prose? How is your process different for each?

RG: Well, with these essays—because I did give myself the task of writing them every day for a year—I knew I’d write them quickly and daily, so I probably knew pretty early on they would not do the work the way a fifteen- or twenty- or fifty-page essay would.

Someone asked me, “Why’d you write essays instead of poems?” and I said, because I just couldn’t write a poem every day! There’s some relationship to unknowing that poems have to me. For this task of writing each day for a year about something, the poem as a form wouldn’t even occur to me, and I just can’t explain it more than that. It’s just something about it.

Z: I left a few of the essays in The Book of Delights feeling kind of un-delighted. For example, “Hole in the Head” is one that was almost completely absent of the delight and lightness many of the essays bring. I’m curious about how concepts like death and violence collide and overlap with delight in this collection.

RG: I think what’s interesting about The Book of Delights is there’s a pretty regular tension where the practice of attending to delight feels like a kind of labor. And the essay you mention tries to begin this one way [with delight], but the gravity of this ongoing brutality we live with takes the essay. So, I think that tension is what’s interesting to me about the book because it’s true to the way I experience life. Which is to say, I am witness to and beneficiary of profound kindness and tenderness and sweetness, and I am also living amid great sorrows, and that sorrow includes and means violence and brutality and the whole thing.

There’s that longish essay, “Joy is Such Human Madness,” where I do that little false etymology of “delight” meaning “of light” and “without light,” and that maybe joy is both at the same time. That’s a long and wandery way of saying that that’s how I think and understand the world and my own life.

Z: Is that the same tension that’s carried through your poetry as well, when you discuss joy and beauty alongside death and violence?

RG: I think so. I recently was looking at that first book [Against Which] and had occasion to look at some of the poems I really had forgotten about, and it was like, oh, this is something I’ve been thinking about hard for a long time, that things reside right next to each other or on top of each other. And in a certain kind of way, I’m interested in it, because I feel like that’s life. But I also feel like there’s a way that understanding brings us closer together, the understanding that the beautiful and the brutal exist. And one of the brutalities of [our way of life now] is that it makes us forget our dying. That’s one of our first commonnesses.

You and I, we’re both going to die. And there are all sorts of apparatuses we could use to avoid or deny that, but I suspect that if we were to just sit with that fact, I think there’s some kind of understanding or knowledge between us that would be allowed to happen.

Z: The Book of Delights seems like a midpoint between your poetry and your other nonfiction. Was writing this latest book of essays then an entirely different process from other essays you’ve written, like “Loitering Is Delightful” in The Paris Review?

RG: I think the essays in The Book of Delights have some of the spirit and the sound of some of my poems, for sure. It’s also the case that I drafted them all in 30 minutes. That loitering piece, though, it took a long time. And it took conversations with people and asking people to read a paragraph or certain parts that were really sticky for me and saying, “I have this wrong, don’t I? How do I get this right?”

There’s a moment in that loitering essay where I say something like, “laughter is kissing cousin to loitering,” and it was my friend Pat who said that laughter is like loitering. He was like, you can’t consume while you laugh because you’ll choke, and that’s where that line came from. Which is to say, I do not write these things on my own. And the ones [in The Book of Delights] that I just really love in a different kind of way are the ones I just couldn’t figure out on my own. And they probably took longer to write, and in that way they were probably more like my relationship to poems.

Z: I love that you’re expressing that you are helped by friends and fellow writers to craft these pieces, because so often writers—young writers, especially—are afraid to harness and wield other people’s language or ideas.

RG: There is this fabrication—it’s a lie—that we need to write these things entirely on our own, and it’s a violence against the truth of our lives, which is that we live in communities.

And that’s what I want to study: radical collaboration—which is constantly happening! It’s all the ways we have the capacity to [share with each other and] love each other, but there is such a profound interference to that capacity. That’s why we need to study the ways we do have those capacities, and that we do it despite these intense institutional and structural pressures that try to impede us from simply being together.