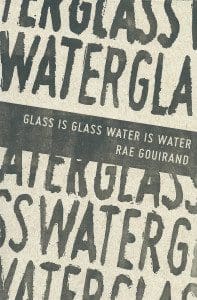

In Glass Is Glass Water Is Water, one of the first full-length books to be published by Spork Press, Rae Gouirand (whose poetry book Open Winter won the Bellday Prize) explores relationships, intimacy, the body, and the tension inherent in wanting to be understood without having to be explicit. Gouirands’ poems push against linear, heteronormative ways of reading and often challenge prescribed forms. Gouirand, whose poems were published in ZYZZYVA No. 102, recently spoke to us about how her work speaks to present-day concerns, such as the MeToo movement, and delved more deeply into her craft.

In Glass Is Glass Water Is Water, one of the first full-length books to be published by Spork Press, Rae Gouirand (whose poetry book Open Winter won the Bellday Prize) explores relationships, intimacy, the body, and the tension inherent in wanting to be understood without having to be explicit. Gouirands’ poems push against linear, heteronormative ways of reading and often challenge prescribed forms. Gouirand, whose poems were published in ZYZZYVA No. 102, recently spoke to us about how her work speaks to present-day concerns, such as the MeToo movement, and delved more deeply into her craft.

ZYZZYVA: One of the reasons I was drawn to Glass Is Glass Water Is Water was that I’d read your poem “Not Marrying” on the Academy of American Poets website, and I thought it contained one of the best illustrations of what consent should look like. The following lines in particular stood out to me:

push back hard when you object to my position.

Divorce me every moment you decide

who you are and where you shouldnext be. . . .

This and the insistence on will—“There is no moment/we could exchange our words. We will . . .” (as opposed to “I do”) and “wherever you find that bending becoming/your will and your innate way. I pray . . .”—were captivating. I’m curious about whether you think poetry can effect social change and has a place in conversations that are political, such as the dialogue surrounding the #MeToo movement?

Rae Gouirand: It’s interesting to me to hear about that poem being read through the lens of consent—it definitely teaches me something. In my mind that poem grapples with the limits and the terms of the compact that any two people can have, and kind of realizes those concerns out loud in the form of this address to the beloved. I wrote it slowly over the course of a year after the Obergefell v. Hodges [Supreme Court] decision was announced in 2015—that summer I was driving back and forth across the country on a 10,000-mile road trip with my partner, having lots of conversations with those I’m close to about the tremendous discomfort I feel around the way the queer movement has prioritized marriage equality.

The book overall chews pretty hard on what meanings, and specifically on what figurative assignments, do and don’t do. I’m coming at that as a queer person, and dealing with the ways meaning gets dislocated or transposed or lost in transit, and that poem was the last one I wrote for the book, and the poem that signaled to me that the book was done. In it I wanted to figure out what the question is that lives past marriage proposal, and how that question can be asked. In writing it I realized I was kind of praying something for the two of us, and also for all queer folks—that we always be willing to ask our questions, and that we always have questions worth asking.

The ways in which I think poetry can absolutely shift the paradigm are mostly invisible, slow, low to the ground, close to the bone, and having to do with keeping individuals here, with helping them stay. Yes, it helps us shift thinking, and it facilitates empathy and curiosity. Yes. Art helps me, and many others, stay here and keep pushing onward or pushing back—any creative impulse that is well-realized helps me remember how much power lies in my ability to make, and invent, and revise the way I interface with the world. Since 2016, many of my students have pointed to that power as mattering an almost unfathomable amount. Ultimately I think the job of the poet is to multiply the number of ways that sense is made, and can be made, and is recognized as sense in this world. I believe that matters; I believe in that labor as a necessary labor. That might be the only belief I have that I would call religious.

Z: Your work made me think of how John Grisham’s wife told him that men don’t write sex well. He attempted to, but his wife’s reaction (she laughed while reading it) convinced him to avoid doing so again. Do you think women, especially queer women, write sex and consent better than men? I ask this because I think the way you describe sex in your poems is very honest. I’m thinking of how you approach sex in “Ice,” which is a really smart declaration of one’s need for both self-love and love from another or others, and “Snoqualmie,” in which the speaker aptly assesses an unsatisfying intimate relationship and/or mediocre sex.

RG: I don’t know the first thing about John Grisham, and also I am distinctly uncomfortable classifying anything based on adversarial or binary gender, but I can say that many, many women writers, and many queer women writers, have written sex in the realest and most complete of ways, while living in and surviving a world that classifies them exclusively as either being too consumable/guilty/deserving of violation or not consumable enough/inadequate/deserving of violation and that forces them to try to pass undetected through their everyday lives, and that I find their full-throated work about sex and desire and agency more powerful as a result.

That writing counts extra to me, because the human and creative labor to get that piece of our reality written and into the record is complicated immensely. And it matters to me that I share that labor, that I write the body and the world in which it is most real and most readable. After my first book came out I made a decision. I specifically wanted to write a book for queer women, about queer women, about the ways that we constantly come up against ourselves.

Most of the poems in Glass explore crises of intimacy—what can and can’t occupy simultaneous sense between individuals, what does and doesn’t find its way through our bodies or our abilities to speak to (or with) one another. To whom, then, do we ultimately find ourselves speaking? The sex in the book is real to me, meaning it routes tensions that, to me, count for something that is not singular, and enables certain kinds of speaking that do not fit anywhere else. The speaker of these poems finds her way into speech through all of the relationships and relationship stories that show up along the way. She is born of friction. Sometimes she sees or speaks double. She is skeptical and (eventually) unblinking.

Z: In your work, there seems to be an emphasis on repetition (as suggested by the titles Glass Is Glass Water Is Water and “Everything Twice,” as well as by the assertion in “Stray” that “we know/to read things twice”). There is also the actual repetition of words in poems like “Blood & Stone,” which ends:

goes from one to many. Stones

always exist. Stones always exist.Stones always exist. Stones always exist. There is no way out of this.

Also, in the first poem in Glass Is Glass Water Is Water, you write:

. . . Every night I wake

at the point I try to speakbecause I am trying to speak.

And you conclude that poem with the couplet “Maybe there are no metaphors,/just what is true and what is true.”

Your use of repetition reminds me of a conversation between Danez Smith and Kaveh Akbar recently published in Granta and in which Akbar, speaking of the use of repetition in Sufism and in other contexts, declares, “Repetition takes us into this ecstasy—it elevates us into an incantatory, near-narcotic state where we become more permeable to language’s emotive and cosmic potential.”

Why do you employ repetition in your own work, and what do you hope to convey to the reader through it?

RG: I tend to think musically. Or I should say feel. My writing comes from a place that is much closer to some kind of pulse than my everyday speech, than my million-miles-an-hour teaching voice or the transactional slippage I use socially. When I am writing I am listening, sometimes straining to listen, and recording what I pick up through listening. I am recording how language changes functions through sustained, vertical listening. Writing for me has always felt like reading in that sense. I used to be an instrumentalist and before I learned how to talk in real time the landscape of musical practice—which has everything to do with geometry, pattern, deviation, and how any given instrument mediates those challenges—was very much where I “was.”

I love what both Danez and Kaveh say in their conversation about the way that element of musicality provides that opening. For me the magic comes from the way that the initial sense we assume we’re slinging around falls right out of any word we repeat. Words loosen and diffuse in repetition. They drop straight down, past their own etymological roots and sense memories, into a kind of molten place before assignable sense. I don’t know if that’s language’s potential being actualized or if that’s something else showing through that’s much bigger than language. The word stones will only hold for a minute before it turns inside out and takes you somewhere else. Stones multiply on you. Stones always exist. Say that line three or four times and you find yourself falling.

Also: I think I’m particularly interested in circularity, in doubling back, in the body of the poem, because echoes and loops feel like such accurate representations for the way I actually experience time. Some moments circle me two or three or four times before I can step out of them and into the next moment. So much of what is humanizing about poetry has to do with the ways that it gives body to these natural nonlinear forms and paths that we take experientially. Our lyrical tendency is often call and response, around refrains we come back to, because we are constantly circling and returning, making our way around the center. I feel like my whole life I’ve been keeping a little secret notebook in which I record evidence of the kinds of messes we get ourselves into when we hold onto the belief that we’re actually oriented forward in a (one) line. The poetic line is as charged as it is because it collapses, restarts, relocates, because it drops down beneath itself as though through a trapdoor, not because it takes us forward. Forward is only one of the directions. In the long term, I think most attention moves in a circle.

Z: A major theme in your work seems to be the tension between trying to be understood and not wanting to have to try—wishing another person could just get it or get the speaker in the poems. However, many of your poems are far from explicit or direct. You even call questions into question by depriving them of (speaking of repetition!) question marks. And you often use some punctuation in place of others we would normally expect. But I see this resistance against unambiguity mostly in the forms you have chosen for some of your poems, which don’t feel like they are meant to be read in a linear fashion. Certainly, there are poems that can most easily be read as two vertical units that make up one poem. Why did you choose this form for those poems?

RG: It’s rare that I use question marks in my poems, or even in my prose. I find myself able to tell where wondering is, where uncertainty is, even when the line or the sentence ends, in the presence of a period. I guess to me the question mark argues that questions stand separate from suggestions, announcements, but they’re often just as exposing, just as baring. Why punctuate differently?

There are seven poems in the collection that present simultaneous bodies left and right, like a verso and recto. In my mind the image is of two hands whose fingers are interwoven pulling against each other. Books have always made me think of hands. No, those poems can’t be read in a linear fashion—while I imagine their components being read (and considered) in proximity to one another, they’re also in conversation as a sequence spread out across the whole book. I see them as trying to sort through the stories, the pieces, that aren’t resolvable, that don’t “get” their own poems, their own space in the archive. Some of them are almost sifting performed in service of other poems in the book. I wanted to include some work in the book that couldn’t be read aloud without being utterly ruined.

Z: Related to form, I noticed how expansive some of your shorter poems can feel. “Ice,” and “Promise” seem to encompass whole philosophies but are fairly short. From a craft perspective, what do you think a short poem should do?

As you likely know, many opportunities available to poets—contests, fellowship applications, etc.—now have line limits, and some believe the long poem is dead or at least currently out of favor at a time when Instagram poetry, which tends toward extreme brevity, is on the rise. What do you think longer poems, such as “Not Marrying,” should do? What is the function of a long poem in a world attuned to brevity?

RG: Short poems isolate and pressurize. In doing so they make an argument about the elements that come together to forge any symbol, and about the relationships between those elements. Like still lives, they are inherently rhetorical and dependent on tension. Long poems find a pace and a pulse and ride it, so that we might come back to earth and back into our bodies for whatever interval they will have us. They are inherently restorative in their tests of tensile strength and flexibility, but (I would say) are ultimately in search of a way to leave the discernible world behind.

Read more of Rae Gouirand’s poetry by purchasing a copy of ZYZZYVA Issue No. 102.