You can’t accuse Joe Donnelly of taking it easy. In a decades-spanning career, the Los Angeles writer has profiled the “who’s who” of Hollywood—from America’s sweetheart Drew Barrymore to iconoclast filmmaker Werner Herzog—in the pages of publications like L.A. Weekly, where he served as deputy editor for a number of years. During that time, his short stories have earned him an O. Henry Prize (“Bonus Baby,” from ZYZZYVA No. 103) and have been adapted into short films. Donnelly also co-founded and co-edited Slake, a short-lived but highly acclaimed journal that gathered journalism, fiction, poetry, and art, all with a distinctly L.A. feel.

You can’t accuse Joe Donnelly of taking it easy. In a decades-spanning career, the Los Angeles writer has profiled the “who’s who” of Hollywood—from America’s sweetheart Drew Barrymore to iconoclast filmmaker Werner Herzog—in the pages of publications like L.A. Weekly, where he served as deputy editor for a number of years. During that time, his short stories have earned him an O. Henry Prize (“Bonus Baby,” from ZYZZYVA No. 103) and have been adapted into short films. Donnelly also co-founded and co-edited Slake, a short-lived but highly acclaimed journal that gathered journalism, fiction, poetry, and art, all with a distinctly L.A. feel.

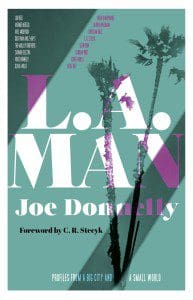

L.A. Man (284 pages; Rare Bird Books) represents a carefully curated selection of Donnelly’s journalism. The book includes profiles of actors as disparate as Carmen Electra and Christian Bale, as well as the madmen and outsiders that capture Donnelly’s imagination: the Z-Boys who skated rings around the empty pools of 1970s SoCal; ex-hippie turned international drug smuggler Eddie Padilla; eccentric comedian and dramatist Lauren Weedman, whose solo theatrical shows Donnelly likens to witnessing The Who perform for the first time; and many more.

Donnelly talked to ZYZZYVA about some of the famous names that appear in L.A. Man, life in the sphere of the filmmaking industry, and the enduring allure of Los Angeles.

ZYZZYVA: Throughout L.A. Man, you have a tendency to profile filmmakers, actors, musicians, and other artistic figures at moments when they’re either established icons (Lou Reed, Werner Herzog)—or alternately right when they’re at the precipice of fame. For instance, you met with Wes Anderson just before Rushmore put him on the map, and you note that even when you spoke to Christian Bale pre-Dark Knight he wasn’t quite a household name yet. When you meet someone at the start of their career, does that tend to make you feel more invested in their career trajectory and want to keep up with their artistic development?

JOE DONNELLY: Not really. I feel like I tend to go all in when I’m doing the pieces, or a lot of them anyway. There’s a desire to make them definitive even if they come at transitional points in the subjects’ lives, and I don’t tend to feel much invested in their trajectories afterward unless, of course, they are figures whose lives and art will continue to relate to my life in a tangible way. Those are few and far between. I don’t have many heroes in that way, though Lou Reed was certainly one of them. Of more interest to me than the super famous figures such as Herzog, Barrymore, Bale, or Penn, etc. are the continuing stories of artists such as Craig Stecyk and Sandow Birk, or Eddie Padilla, the subject of “The Pirate of Penance,” and the wolf OR7, whose life and story has more implication to me than whether or not Wes Anderson makes another good movie.

Z: You also return to profile Wes Anderson at perhaps the lowest point of his career to date, when his (relatively) big-budget The Life Aquatic tanked at the box office and The Darjeeling Limited met with a somewhat lukewarm critical reception. You mention, “One catches a whiff of schadenfreude for the wunderkind,” and the backlash for a director like Anderson often seems like it has less to do with their creative output, and more to do with the media’s love of a highly publicized fall from grace. Do you change your approach to interviewing when you’re meeting with a public figure who is in the midst of a vulnerable moment? It was then interesting to see the flipside when you met with Sean Penn during what might be called a vulnerable moment for yourself, facing an impending divorce.

JD: I noticed that a lot of these pieces were done during a personal rough patch. I tend to be highly productive during those times, not surprisingly, but it’s also a great time to relate to people, perhaps a more empathetic time. But regardless of what emotional state I or the subject may be in, or when the assignment is taking place, I try to get “real” real fast. Subjects relax when they can see you’re just a person trying to have a real conversation and see them as real people, too. I’m usually pretty relaxed in these situations, for whatever reason. Maybe because I started out early interviewing folks like Ray Charles and George Clinton and Jack Kemp for this little newspaper in Vail, Colorado, before I even knew writing would be a career. I got thrown into the deep end early.

Z: I love how frank you are throughout the collection when you’re not a fan of someone’s latest work, whether it’s discussing Rescue Dawn with Christian Bale or mentioning you didn’t care for the ending to Fantastic Mr. Fox. Do you think in a roundabout way it makes your subject trust or respect you more when you’re that frank with them? As you say in the book, “Every interview is a date and every date is an interview.”

JD: I do think it makes the subjects trust or respect you more, if done the right way. I wouldn’t lead with that. You have to build up some rapport and you have to know what you’re talking about, not be half-baked. But, I came of age when writers and those writing about them almost had relationships and they were sometimes confrontational. Lester Bangs and Lou Reed come to mind. In the end, though, we can all smell disingenuousness and nobody wants to be falsely flattered. I don’t mind flattering at all, so long as it’s honest. And, also, we’re talking about art and life. It’s not interesting without acknowledging the conflicts and warts and all.

Z: The book illustrates how no matter the venue—whether it’s skateboarding or filmmaking—the struggle for anyone with a passion is finding that balance between artistry and commercialization. I loved what professional surfer Chris Malloy said in your interview with him: “At first, it’s ‘Hey, I can pay my rent and get to do what I love.’ It goes from having enough money to pay rent and barbecue to having your face on billboards and MTV and people in the Midwest wearing the stuff you’re hawking, and you realize maybe you’ve gotten into more than you thought you were. After a while, about five years, it’s become apparent you’re a trained seal. It’s wear the trunks, wear the shirt, smile. Don’t say too much when you’re interviewed and everything will be fine.”

Is this a thread you noticed emerging in many of these pieces? I wonder if you related to that view of runaway success, as you mention in L.A. Man that you made a deliberate attempt to steer away from celebrity interviews around the mid-2000s, only to be drawn back to them again.

JD: Well, I can’t stand most pro-forma celebrity interviews and have little interest in celebrity or celebrities unless it’s indicative of a larger cultural phenomena –– if that person is an avatar for larger cultural trends, as it might be argued Carmen Electra was a precursor of sorts. But, I don’t think I’ve done many “celebrity” interviews in my career. Oh, yeah, I did do one. It was with Seth Rogen, one of those cattle calls. It was for a British newspaper, maybe the Times of London. It was one of those, “You’ve got twenty minutes with Seth in this hotel suite.” Very controlled. It sucked, but I needed the money.

I’ve probably done a hundred of these profiles, and more than half have been with subcultural icons along the lines of Craig Stecyk, or the Malloys. When it is a “celebrity” I’ve said no far more than I’ve said yes. I didn’t get into journalism to be a culture writer, but that certainly became a strong current in my career and, of course, being in Los Angeles had a lot to do with that.

The truth is, though, it’s getting harder and harder to do the sort of spontaneous things you find in this collection. Everything is so managed now and social media and digital has had a dampening effect. I have a pretty wild, long-form profile coming out in The Surfer’s Journal on this amazing guy, Danny Kwock, this punk-rock, street-kid surfer who transformed the surf industry and ended up in some ways a casualty of his own success. I spent hours and hours with him. We were both kind of shaken and in tears at the end of it. The opportunities for that type of connection and conversation in the pursuit of this type of storytelling seem few and far between now.

Z: One of my favorite parts of L.A. Man is when you describe doing research for your interview with Christian Bale, a process that involved you heading to Blockbuster Video to rent several of the movies he’d starred in, including the seemingly impossible to track down cult flick Equilibrium. (One video store clerk exclaims, “That movie is awwwwesommme!”) What do you enjoy most about your particular research process when you’re about to profile someone for the first time?

JD: Well, I’m a pretty curious person, so the discovery process in journalism is almost always fun, regardless of the subject. But in mining the filmography of an actor such as Christian Bale, someone who’s made interesting choices, you become more culturally literate by research and by osmosis. You start to see the connections and threads and cultural history at work in film, or art, or even just pop culture. The Z-Boys story, for instance, is full of cultural hieroglyphs and artifacts that have informed and shaped the current language. I like learning those languages and that cultural history. It’s anthropological in many ways.

Z: Toward the final section of L.A. Man, the reader encounters a series of pieces that feel like they come from a personal place, and many of them seem to speak to the legacy of California as a whole. “The Pirate of Penance” examines the life of Eddie Padilla, a former member of the hippie organization Brotherhood of Eternal Love who later staged a death-defying prison break that would be hard to believe if it took place in the middle of a summer blockbuster. Padilla seems prone to self-mythologizing, and as you spoke to him you disrupted his attempts to romanticize his violent past. You write, “I’m not a fan of hippies and their justifications for what often seems like plain irresponsibility or selfishness.”

JD: My first approach with Eddie Padilla was to make sure he wasn’t full of shit. I did a hell of a lot of reporting before we even met. I tracked down the priest who sheltered him and Richard Brewer when they escaped from Lurigancho [a prison in Peru]. I tracked down folks who worked at Lurigancho during that time to confirm his tales of brutality, in particular when troops opened fired on the place like it was a strategic site in a battlefield. I talked to the mother of his femme fatale ex, Dianne Pinnix. It was really a massive investigative project to verify his narrative, which, despite his grandiosity, checked out. Eddie is, in fact, a larger than life figure. His story is incredible and true. But he’s also a failed and flawed human and the parts of his story that needed to be confronted were his own conflation of the epic with the heroic. I tried to hold his feet to the fire and not get caught up in the myth and confront him when he was being self-mythologizing. Eddie learned a lot of lessons in humility along his truly epic journey. One of the most poignant moments in my reporting was when he broke down in tears and admitted that he wasn’t really the hero of his own story, that Richard Brewer was. I think Eddie became most heroic in these later stages of his life, after his own hard-fought recovery, when he became more in service to wounded, fallible humans like he is. I visited with the other survivor, and it didn’t appear to me that he had made his way back to the community of man in the way that Eddie has not only made his way back, but is trying to help.

As you referenced, this would seem to be great fodder for the movies, and the fact that this story hasn’t been snapped up by Hollywood (shameless plug—a man’s gotta eat!) is hard to understand, except that Hollywood gatekeepers, as opposed to the actual creatives, sometimes seem to have trouble differentiating between a topic or an idea and a real, compelling narrative. (See, I just shot myself in the foot, again.) In the end, despite his occasional flair for aggrandizement, Padilla is quite a story one that, as you noted, contains multitudes.

Z: In “Lone Wolf,” your quest is to try and catch a glimpse of OR7—the technical designation given to the seventh wolf collared in Oregon—as he made his way into California. OR7’s lonely journey into Northern California had the locals in Plumas County on edge, to say the least. Although this piece originally ran in 2013, I was struck by the similarities of Plumas County dwellers’ reaction and the tenor of the country in the months leading up to the 2016 election; it’s easy to detect that same xenophobia, redirected economic rage, and longing for simple solutions to complex problems. Was our current cultural divide on your mind as you selected this piece for L.A. Man?

JD: Absolutely. I was in a place of spiritual and civic malaise when I started pursuing that story. I couldn’t sustain Slake anymore, which had been an extremely defiant and optimistic undertaking. The politics of Paul Ryan and Scott Walker, these Ayn Randian fools, hucksters, and vampires, were on the rise nationally. The spirit of the Occupy Movement was waning. There weren’t a lot of places to look for spiritual sustenance.

Then came this amazing wolf into California, staking out a claim in the very place where the last of his kind had been killed off 90 years prior as the merciless wheels of Manifest Destiny kept rolling. This happened in the late winter of 2011, when the ideology, culture and economics of Manifest Destiny were so obviously bankrupt. We need to move into a new frame of mind, something that’s apparent to anyone who isn’t still subscribing to Chicago School economic theory. The old ways—not the old, old ways, the Manifest Destiny ways—are dead and dying. We just haven’t caught up to that culturally. But the transformation into something new and sustainable is painful.

On the one hand, the vampires are trying to squeeze every last drop of blood out of utilitarian, resource-exploitation capitalism. On the other hand, the “new economy,” the one that is bringing coffee shops, galleries, and eco-tourism to places like Joseph, Oregon, from whence OR7 came, are not sustaining communities. Communities like Joseph, Oregon, are sort of collateral damage in these huge shifts that we are undergoing. How we confront those shifts is, I believe, critical to our futures. Wolves coming back in general, and OR7 staking a claim in California in particular, carry all the narrative freight about us and our times you could possible ask for if you want to look at these issues. He’s an incredible gift in that way.

So, yes, I think the so-called “wolf wars” are more relevant than ever because we have a chance to do things differently now. The story of the reintroduction of wolves to the West is epic, dramatic, and redemptive. But it’s not over. What happens at this critical juncture, in these less magnanimous and more retrograde times, will tell a lot about who we are and where we are going. And, of course, it goes way beyond wolves. To cop from the great L.A. band Los Lobos, the question isn’t so much “How Will the Wolf Survive?” but how will we survive without the wolf?

Z: Over the course of this book, you capture so many different sides and times of Southern California—from the Z-Boys in their gritty Seventies era (“We surfed while America went down the tubes,” says Skip Engblom) to the more flashy, MTV vision of L.A. life. After all these years, does L.A. remain a place of great fascination for you?

JD: It does. Los Angeles is vast, unfathomable, difficult, and rewarding. I tend to think it’s the most important social experiment going on at this time in our country’s history. It’s bearing the burdens and privileges of modern life like no other city I know of, and I’ve lived in a lot of them. How it fares, I think, will say a lot about our destiny. I’m worried for it and us because Los Angeles’ advantage over culturally and economically stratified places like New York has long been how it has afforded space—socially, economically, intellectually, creatively—in which to stretch out. That space is getting more and more expensive, though, nipping at New York’s heels in terms of inaccessibility. I fret for that. But, like Werner Herzog, who calls L.A. “the city with the most substance,” I remain optimistic for Los Angeles and for the experiment it represents.

I don’t tend to feel much invested in their trajectories afterward unless, of course, they are figures whose lives and art will continue to relate to my life in a tangible way. Those are few and far between.