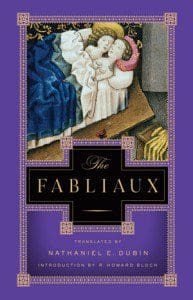

Nathaniel E. Dubin’s collection of Old French comic tales in translation, The Fabliaux, is as deceptive as one of the fabliaux themselves. Published by Liveright, an imprint of Norton, in a sumptuous and hefty hardback (almost 1,000 pages long, including Dubin’s bibliography and explanatory notes), the elegantly designed front cover has the title gold-stamped and centered on a prominent black cross; even the couple demurely posed in a bed above the cross (taken from a medieval manuscript) have gold embossing wreathing their heads, lending them both a saintly air.

Nathaniel E. Dubin’s collection of Old French comic tales in translation, The Fabliaux, is as deceptive as one of the fabliaux themselves. Published by Liveright, an imprint of Norton, in a sumptuous and hefty hardback (almost 1,000 pages long, including Dubin’s bibliography and explanatory notes), the elegantly designed front cover has the title gold-stamped and centered on a prominent black cross; even the couple demurely posed in a bed above the cross (taken from a medieval manuscript) have gold embossing wreathing their heads, lending them both a saintly air.

All this lends The Fabliaux, as a physical object, a sense of serious, even Biblical scholarliness. But this tone is upended quickly upon even a cursory examination of the contents. (I was reading The Fabliaux while riding to work on a crowded bus, when a middle-aged woman plunked down into the seat next to me. From the corner of my eye I saw her assess the meaty reading material in my hands. She might have assumed I was some sort of dutiful student; then she leaned closer and caught a glimpse of what I was reading. “Trial By Cunt,” proclaimed bold black italics at the top of the page. The woman recoiled as if I’d bitten her.)

Fabliaux, after all, are comic tales written in French between the 12th and 14th centuries. For English readers, the most famous English poet to work with the fabliau form is probably Chaucer, whose Canterbury Tales abound with both the courtly, such as the romance of “The Knight’s Tale,” and the comic, as in “The Miller’s Tale,” which capitalizes on both adulterous escapades and potty humor. (The tale ends when the young student sleeping with the carpenter’s wife farts in his rival’s face, causing the rival to burn his “ers” with a hot poker).

The fabliaux are important not only for their approach to humor, but for their focus on sex, class and wealth, and bodily functions like eating and defecating—all elements quite absent from more highbrow, courtly, or Church-sanctioned religious texts. (Though many of the fabliaux do end with a brief mention of some sort of moral to be gained, they’re often tongue-in-cheek.) This focus on realism (but only to an extent—the people depicted in these stories are still all quite stylized), as well as the fabliaux’ relative brevity, has led them to be declared the “ancestor of the short story,” as medieval scholar R. Howard Bloch writes in the book’s introduction. Despite this noble background, fabliaux, generally, have been neglected by the academic community; Liveright’s edition serves as the largest and most complete collection of fabliaux, in English or French, ever published “for the general reader.”

Most of the fabliaux translated here are funny and charming in their bawdy audaciousness. (Dubin takes care in his translations, retaining the driving rhythm and rhyme of the originals, which appear here next to their English versions.) Multiple tales use constipation, farting, or other intestinal travails as plot devices, and almost all of them involve adultery. A few are also disturbing, especially for a modern audience. In “Master Ham and Naggie, His Wife” (where the wife’s name immediately gives away her nature), Ham ends up fighting and then viciously beating his wife “because she didn’t give a damn/for making an attempt to please/her husband.” Instead of cooking him beans, like he’d wanted, she serves him “sorry greens” instead. The moral here is that if one’s wife will not be “brought in tow,” one should “beat her good/so every bone [is] black-and-blue.”

These fabliaux are obviously products of their time, so it might be surprising to read women frequently presented in these tales as active agents of their desires and as more than able to flout social strictures to fulfill them. (Surprise may turn to dismay when these portrayals are contrasted against the treatment of female characters in far more contemporary stories.) One woman, “the wife of an equerry / from around Chartres …was sleeping with a prelate/whom she adored, as he did her. / For no one’s sake would she defer/ doing with him as she saw fit.” Her dim-witted husband gets suspicious, so she tricks him into believing her midnight disappearances are because she’s going to church to pray for their unborn child. His fears assuaged, she’s free to carry on with her prelate. “A woman married to a dunce / so says Rutebeuf, gets what she wants,” the narrator concludes.

The gullible husband tricked by a clever, ridiculous scheme is a common trope here. In “The Peekaboo Priest,” a lecherous priest peeks through a keyhole to look in on a married couple eating dinner. He cries out in shock; when the husband inquires as to the problem, the priest scolds him for having sex in the kitchen. The husband protests that they’re only eating, to which the priest tells him to come have a look for himself. The men change places, and the priest immediately pulls the wife onto the table and “thrusts and butts” into her. The husband protests, but the busy priest exclaims that despite how it looks, he’s just sitting there, eating his dinner at the table. The husband is convinced.

The “bed trick” is another recurring trope. In “The Miller of Areleux,” a miller convinces a young, lovely virgin into staying at his house so he can “grind her wheat” the next evening. Revolted, the young woman confides in the miller’s wife, who has her sleep in her bed that night while she takes the guest bed. As the wife expected, the husband comes in from work and unwittingly makes love to her five times; then he invites his friend in, who goes another five times. In the morning, the wife is furious that the miller’s been holding back his enthusiasm for so long, and the miller is dismayed he let his friend sleep with his wife.

The Fabliaux also features tales hinging on riddles, tales denouncing the corruption of the priesthood, and, a personal favorite, tales employing obscure and highly euphemistic sexual metaphors (and lots of puns to boot). In “The Maiden Who Couldn’t Abide Lewd Language,” for example, a prudish maiden explains naively to her seducer that he’s grabbing “her meadow,” in the middle of which is “a spring, / which right now isn’t overflowing.” She goes on to explain that beneath her spring lies “a bugler…standing sentry. If man or beast sought to gain entry/and … drink from my clear spring / the sentry would start trumpeting.” In reply, Davy explains that his “pony” needs watering, and that his two “stable boys” can beat her sentry into silence; she eagerly assents.

Even if the fabliaux in this deluxe volume aren’t serious, they are certainly important as cultural and literary artifacts. But of more importance, The Fabliaux is a reminder that medieval texts can remain engaging, lively, and, above all, funny.