On page after page of Matthew McIntosh’s theMystery.doc (Grove Press), redactions black out key words, crucial questions, and even whole sections of text. I don’t know how far I had gotten through the 1,660-page novel before I stopped expecting the eventual, climactic unveiling of the hidden words, the code-break that would deliver me from all my head-scratching. Surely, it was hundreds of pages after the flip-book sequence that begins on Page 73 with a voice shouting, “>HEY” (flip page) “>DO YOU THINK YOUR SAVIORS COMING BACK” (flip page) “>WHATS HE LOST DOWN HERE”—before I stopped looking for whatever it was that had been lost in those black blocks and began to focus, instead, on the strange constellations of voices and images arranged around the voids.

On page after page of Matthew McIntosh’s theMystery.doc (Grove Press), redactions black out key words, crucial questions, and even whole sections of text. I don’t know how far I had gotten through the 1,660-page novel before I stopped expecting the eventual, climactic unveiling of the hidden words, the code-break that would deliver me from all my head-scratching. Surely, it was hundreds of pages after the flip-book sequence that begins on Page 73 with a voice shouting, “>HEY” (flip page) “>DO YOU THINK YOUR SAVIORS COMING BACK” (flip page) “>WHATS HE LOST DOWN HERE”—before I stopped looking for whatever it was that had been lost in those black blocks and began to focus, instead, on the strange constellations of voices and images arranged around the voids.

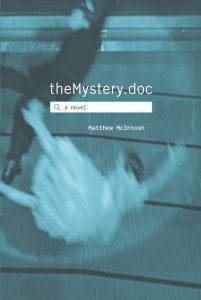

It can be difficult to recognize a work of real vision. At times McIntosh’s book is profoundly un-fun to read. Without warning the text breaks apart into a cacophony of (seemingly) non-sequitur plot shards, screenshots from classic films, and blips of (seemingly) random dialogue separated by long stretches of emptiness or indecipherable symbols. An uncharitable reader could easily fill up all the black and blank space in this book with dismissals. But the author’s formal trickery can’t be written off as merely evasive, pretentious, or coy. Setting aside the reader’s perfectly valid expectations of entertainment and pleasure, theMystery.doc is some sort of masterpiece—obscure or vulnerable by jagged turns, but in every moment energized by a self-assured sense of purpose: the novel knows, even if you are, for a long time, completely in the dark.

McIntosh employs a grand-scale version of the interlocking vignette structure that made his first book, Well, such an exciting and unique debut. Particular voices and narratives emerge, vanish, and recur over the span of several-hundred-page chapters. A photo sequence begun on page 325 returns on page 1,600. The story of a drowned couple is told and retold. The Twin Towers fall again and again. The novel accumulates meaning the way many mosaic-style works do: by the resonances (or dissonances) created between fragments, and—more mystically—by a kind of sustained déjà vu, which reminds us with echoes of familiar dialogue or repeated photos that no detail is irrelevant to the larger image being composed.

Surprisingly, the novel’s text-and-image format shares very little DNA with the glossy-paged projects of a writer like Mark Z. Danielewski. Instead, imagine W.G. Sebald doing his best T.S. Eliot impression—archival photos and plot-less autofiction thrown into a meticulous formal blender. (This comparison to Eliot is one other writers have noted, too, and which author Alan Moore mentions in his blurb for the novel.). Or, think of E.L. Doctorow’s post-modern, post-Christian opus, City of God—one of this novel’s closest literary relatives. Like City of God, theMystery.doc sets itself up as a kind of writers’ sketchbook, filled with iterative entries on physics, alter-egos, philosophy, film, and plans for the composition of the very book in your hands. And like Doctorow, McIntosh never strays far from metaphysical concerns; both authors set off in search of the divine.

“[The] composition of a mandala,” McIntosh writes, “is meant, as I see it, to encapsulate God by building his universe around him, piece by piece. At the very center, there is often an image / to find your way.” This, near as I can grasp, is the novel’s main project: to evoke fragments of the whole universe and set them swirling around some unifying core. These fragments include a brief history of the cosmos, finally zooming into Seattle circa 2003, as well as a fascinating piece of speculative pseudoscience predicting the discovery of a mysterious “{ } particle,” the quantum foundation of “memory… perception… consciousness”—of all human meaning and of the experience of time. Interspersed with such richly imagined concepts are a deluge of documents—transcripts of conversations with family and friends, pages from Cervantes and Joyce and Ovid and the Book of Job, internet search results for missing persons, photos and screenshots, emails, letters, and hospital records. (At least, we might believe these are all real documents—the sustained meta-fictional dimension of the book aggressively resists categories such as autobiography or nonfiction.) All of these elements, invented or recorded or distorted, become pieces of the book’s universe. Yet at the center of McIntosh’s mandala is no image at all. At the center of the mandala is —a sacred, unspeakable Mystery, perhaps. Or else: just empty space—“just loss,” as the writer puts it. What matters is whatever meaning he can carry into that space.

Amid such existential uncertainty, the writer’s uncompromising tenderness toward family (I hesitate to say his family) serves as a vital emotional anchor. Next to the narrator himself—whose name, like the author’s, is Matt—the narrator’s wife is the most sustained character in the book. In another novel, her portrayal might come across as overly affirming or too sweet. She never says an unkind word or betrays an ounce of resentment toward a husband with some pronounced man-boy tendencies. (When the two of them start spitballing ideas for Matt’s book, she’ll often say things like, “that’s so cool… that is so cool.”) Where in other circumstances we might need to see some flaws, Matt’s completely admiring portrayal of the person he loves is refreshingly uncomplicated in the midst of utter formal chaos. So when the author shows us a blurry photo of (presumably) the wife lying on their bed next to (presumably) him, peaceful and at ease, we can enjoy the simplicity of their care for one another as she says, “Remember when we went to the Japanese garden? …There was no one there… It was so nice.”

Two of the most compelling and thoroughly developed narratives in the novel address the loss of family: Matt’s niece, born prematurely, dies soon after coming home from the hospital; and his father, diagnosed with brain cancer, physically deteriorates and loses control of his language faculties as he nears death. McIntosh’s approach to these stories is not radically different from the ways he deals with his more esoteric topics. Most of what we find out comes by way of conversation transcripts and other recorded messages, and the documents themselves are broken up and scattered, in part, throughout the account of a “quantum surgeon” freezing time to dissect the “{ } particle.” Yet the family’s story completely transforms the meaning of those documents. No longer some kind of data dump, not just a representation of the “drawerful of jpegs, tifs, pdfs, mp3s, midis, wavs, miffs, mpgs, [and] movs” that will outlast us: the transcripts of a mother tending to her fading partner, or a young child telling her uncle a magical story to cope with the death of her little sister, are heartbreaking. Juxtaposed against so much high-concept invention and formal strangeness, there’s a clarity to this devastation. These voices dignify personal love and pain, and they suggest at least one source of meaning, even as the novel struggles against the impenetrable mystery, holy or empty, at the center of it all.

John Dixon Mirisola’s work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, and Flaunt. He holds an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of California, Riverside, and is currently working on a novel.