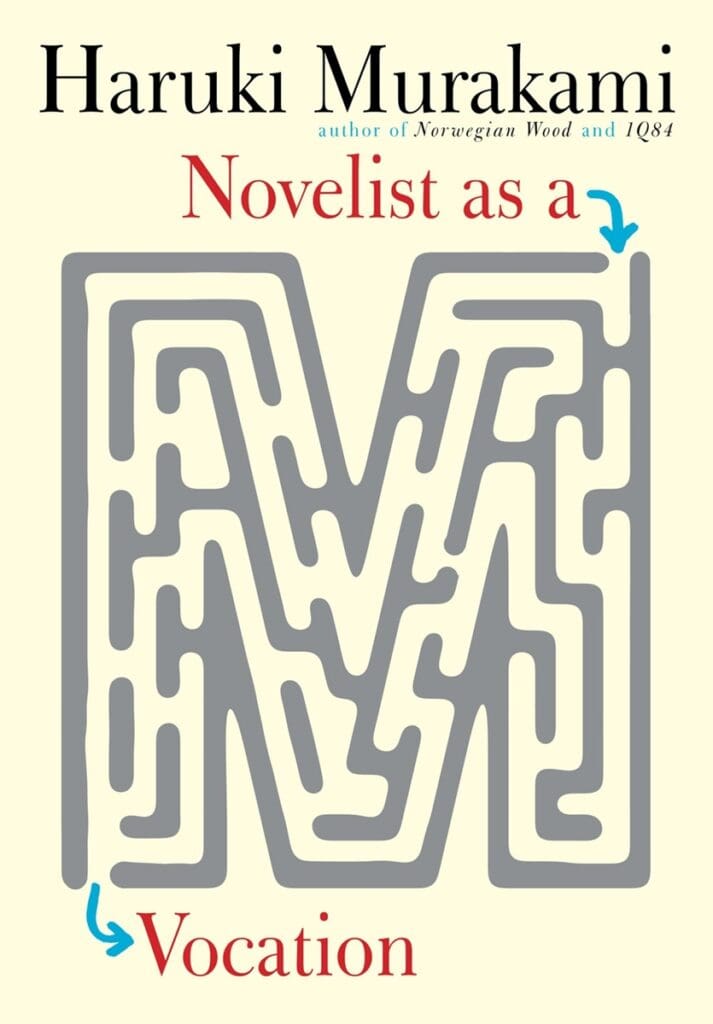

Novelist as a Vocation (224 pages; Knopf; translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen) is Japanese literary icon Haruki Murakami’s comprehensive look at his expansive and prolific career, a collection of thoughts on the process, substance, and form of novel writing, as well as the habits that make for a successful novelist. The autobiographical essays chart his path as an author over thirty-five years, spanning from his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, to more layered and formally complex works such as Killing Commendatore. As a whole, the pieces provide a glimpse into the mind and career of a man whose oeuvre offers a richly imaginative and singular perspective on life.

Intended not as a practical guide so much as a record of Murakami’s thoughts, these essays reveal aspects of the author’s character and creative process that are otherwise overshadowed by his distinctively fluid prose. In self-effacing fashion, he explains that for him writing novels is “nothing less than expressing yourself,” and that doing so as a profession is chasing a “sense of amazement.” These reflections are all the more refreshing in that they’re composed in an intimate style, as though he were addressing a small gathering or chatting with friends at the jazz café he once ran with his wife.

“I can’t help thinking that novelists share something in common with those who spend a year or more assembling miniature boats in bottles with long tweezers,” he writes of the “intricate … virtually endless” operation held “behind closed doors.” With endearing candor, he recalls his debt-ridden college days and his youthful attempts to break into literary society. He recounts the challenges faced by those with literary inclinations, from achieving a consistent output to the snail-like process of working without applause until a project is revised and completed.

The hard part, he maintains, is keeping up the work; many novelists simply give up, while the writers he refers to as his “colleagues” succeed because they have the right temperament—their lives are largely unglamorous. Drive and perseverance, often more than raw talent, are what have made these authors’ careers: “Those who end up writing a novel do so because they have to,” he says. “And then they continue.”

As a young man, what set Murakami apart from other writers, he says, was his ignorance of contemporary Japanese literature and his lack of writing experience. At a Yakult Swallows baseball game, however, he had an epiphany. As though snatched from thin air, he realized he was capable of producing a novel. His approach was unconventional: he wrote the opening of Hear the Wind Sing on an old Olivetti typewriter—in English. With his limited vocabulary and command of the language’s syntax, he translated the work into Japanese, in the process developing a style and creative rhythm that was direct and unassuming, a “new style of Japanese” that was uniquely his.

The literary world of modern Japan is a robust topic of discussion throughout this essay collection, as Murakami digresses on his distance from the establishment and media circus and their reliance on laurels such as the prestigious Akutagawa Prize. He does so humorously, often sardonically, sharing how he was once lured into a bookstore, only to feel embarrassed when seeing a stack of books titled The Reasons Haruki Murakami Failed to Win the Akutagawa Prize. Though he downplays the importance of prizes, instead valuing good readership, he allows that “Literary quality is inherently formless, so prizes, medals, and such provide that concreteness.”

Famous for his love of music, Murakami also tackles the subject of artistic originality through the sounds of the Beach Boys, Igor Stravinsky, Gustav Mahler, Franz Schubert, and Thelonious Monk, among others. He explains the difficulties faced by artists who are today considered “classic”—such as the Beatles and Bob Dylan—and what that has meant for fans who want their favorite musicians to fit into narrow categories.

In considering his own place as a writer, Murakami emphasizes the importance that Japanese culture places on harmony, describing the sociopolitical framework of his native country and how a lack of precedent for the kind of novels he wanted to write made it hard for him to go against the system when he started out. He reveals that the heat he took upon launching his career made him decide to live abroad, prompting him to write Norwegian Wood, a work that catapulted him to fame and allowed him to achieve financial security. He writes, “More than being artists, novelists should think of themselves as ‘free’—‘free’ meaning that we are able to do what we like, when we like, in a way we like without worrying about how the world sees us. This is far better than wearing the stiff and formal robes of the artists.” With this freedom came some discouraging experiences that challenged him when he was finding his way—everything from trying to craft novels in noisy cafés and thin-walled apartments, couples next door making him lose his focus. Today, he writes, he smiles when thinking of those days.

The “desire to write”—an unstoppable personal motivation—has allowed Murakami to overcome all matter of external interference with his writing process, and his words on maintaining stamina should serve as a salve to writers everywhere as they attempt to reach toward the boughs of professional recognition. Strength from physical activity is key to this stamina, he believes, and vital in order to summon focus and concentration. Whether on freezing mornings or hot afternoons, he makes running a part of his routine, as he explained in his delightful 2007 memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running.

Drawing insights from the lives of renowned authors such as Anthony Trollope and Franz Kafka, Murakami stresses the underappreciated significance of leading an ordinary life. From his perspective, the “idealized image of the unconventional” is unwarranted; internal chaos, to him, will always exist. What’s of true merit to him is a “quiet ability to focus, a staying power that doesn’t get discouraged, and a consciousness that is, up to a point, firm and systematic”—qualities he concludes are essential for a successful novelist.