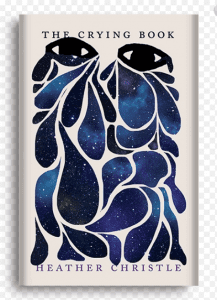

Over the course of The Crying Book (208 pages; Catapult Press), Heather Christle examines the phenomenon of crying from every possible angle: social, cultural, biological, and historical. She asks the tough questions, ones that science still can’t answer: Why do we cry? And what does it mean to cry? Christle’s inquiry is rigorously researched, but it is also deeply personal. While she was writing The Crying Book, she was doing a lot of crying herself, grappling with depression, mourning the passing of a dear friend, and preparing to become a mother.

Over the course of The Crying Book (208 pages; Catapult Press), Heather Christle examines the phenomenon of crying from every possible angle: social, cultural, biological, and historical. She asks the tough questions, ones that science still can’t answer: Why do we cry? And what does it mean to cry? Christle’s inquiry is rigorously researched, but it is also deeply personal. While she was writing The Crying Book, she was doing a lot of crying herself, grappling with depression, mourning the passing of a dear friend, and preparing to become a mother.

The scope of The Crying Book is surprisingly vast—we learn as much about crying as we do about grief, art, motherhood, and Christle’s life. As she conducts and shares her painstaking research, she is also intimately attuned to her pain; she weaves together her examination of crying with her personal experiences, studying tears while shedding them herself. The result is a book that is as informative as it is profoundly moving. ZYZZYVA spoke to Christle, whose poetry was published in Issue No. 114, about The Crying Book via email.

ZYZZYVA: Throughout The Crying Book, you play with the relationship between researcher and subject, and you’re constantly straddling the line between the two. On the one hand you’re conducting a meticulous, thoughtful study of crying; on the other, you are the often the one who is doing the crying. Can share a bit about your experience as both a researcher and subject while writing the book, and if there was any tension between those two roles?

HEATHER CHRISTLE: I think I felt that tension not as discomfort (which the metaphor of tension often expresses), but more literally as a physical sensation of being stretched in different directions. There would be moments when I was crying, or when I was with someone who was crying, and I would both be in that space and simultaneously recall some fact about crying that would make my awareness shift. It made me feel I was in several places at once, with a string of consciousness held taut between them. On the whole, I think it helped me maintain my humility, knowing that my reading would not release me from being a crier, from being described.

Z: In many ways, The Crying Book is as much about mental illness as it is about crying, and the book contains some of the most lucid (and accurate) descriptions of depression that I’ve read. You personify despair so that it becomes this parasitic but still authoritative presence, one with a clear agenda. “Despair,” you write, “wants me not to know the difference between itself and me.” Was it challenging to describe despair so precisely, or was it liberating to put it into words?

HC: I didn’t experience it as a challenge, but nor was it exactly liberating. I feel the same satisfaction about shaping an accurate description of despair that I do about shaping an accurate description of other events, I think. It would be nice to be liberated from despair, but for me it does not work that way. This is true of writing about anything personal. I mean, describing—for instance—the way an elderly man on an overnight flight last week kept waking me because he was overcome by the need to whistle the kind of tune that says “I am nonchalantly waiting for time to pass and generally happy to do so, though this very whistle suggests I require your recognition of this circumstance and therefore my good-natured patience has certain limits around it” feels pleasant, but it can’t make me any less tired. The describing makes something else happen. It generates a new sensation, but does not, for me, replace the one being described.

Z: You touch on the experience of crying in public, and the shame that can be attached to that. You talk about how some people might “hide behind a lie about allergies or a cold,” and about how people on airplanes devise special methods to conceal their crying (men hiding under blankets, women pretending to have something in their eye). In your research, what did you learn about the relationship between crying and shame, especially in regards to crying being seen as a (gendered) sign of weakness?

HC: First off, I feel like it’s important to note that virtually all the research I encountered around gender and crying treated sex and gender as binary and synonymous. I would love to read a study that took a more accurate view. (This seems totally doable! If there can be a “feminist, anti-colonial lab specializing in monitoring plastic pollution,” why not one specializing in tears?) So, with a recognition of the limits of the currently available information, I’d say that shame and crying can be very intertwined, that crying need not feel shameful, but if an audience—real or imagined—responds to a person’s tears with disgust or annoyance, shame can result. The quality of the response of that audience is often rooted in the identity of the crier, and whether they see the crier’s tears as appropriate, given all the expectations they might have for a person inhabiting their particular identities. Lastly, I’ll just say that there can be enormous gaps between the stories people tell about their beliefs about crying and gender (as a sign of strength, weakness, power, vulnerability, etc.) and how they actually respond when in physical proximity to tears (whether their own or others’).

Z: I’m fascinated by this image you posted on Twitter of a tool you used to edit The Crying Book, which envisions the book’s various strands as colored squares on a grid. I think this grid does a great job of demonstrating visually how complex but thematically unified the work is. Can you talk a little bit about this visualization, how it came to be, and perhaps clue us in to what a few of the strands are?

HC: It was so helpful to make this chart. I was struggling to maintain (or even create) a sense of the book as a whole, to apprehend its entirety. Any moment I examined felt like it had its own centrality, like it insisted on all the rest of the book being seen in relation to it in particular. I had to take action to make the book into something other than words, and to contain it within a single page. I knew if I did that, I could hold each moment in place and understand the entirety of their relations at once. And adjust them! Yellow represented science; green represented language and literature. I assigned shades of blue to different phases of my own life. Some passages contained only one color; others had several, and so the line of the book thickens and thins across the page. It would be hard for me to overstate how soothing this process was. I kept my colored pencils very sharp.

Z: In your Author’s Note, you talk about how conversations with friends helped shape the book, saying it would have been “impossible to write this book without their company.” What are the roles of collaboration and conversation in your creative process, both as a poet and an author?

HC: So much of The Crying Book is about the relationships between things, between ideas, places, people. Formally, that’s at the core of the book. I am endlessly curious about what happens when entities are in conversation, what unexpected angles they illuminate in each other. Early in my poet life, I witnessed Joshua Beckman and Matthew Rohrer composing collaborative poems one word at a time, in front of an audience. I was enthralled; I was inside the poem, watching it build. For a long time after, I made poems that way on my own, one word at a time, feeling where the language could go. I love to be inside friendship as well, to watch it grow and change, to watch how we shape and hold each other. Conversation, when it is real, when it moves beyond recitation, is one of the great joys of my life. At the most basic level I learn so much of what I should read from my friends, and The Crying Book is hugely influenced by that, but the gift of their company is so much more. Company! The ones with whom one eats bread! I love this etymology. I love the sense that nourishment comes not just from food, but from its sharing.

“I’m fascinated by this image you posted on Twitter of a tool you used to edit The Crying Book, which envisions the book’s various strands as colored squares on a grid.”

The link to this is dead but I’m so fascinated to see it. Any chance we could get the image here?