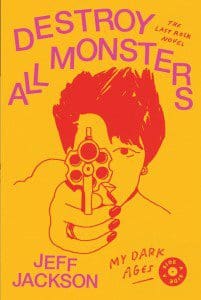

To the young, music can be a religion. Destroy All Monsters (357 pages; FSG), the latest novel from Charlotte-based author Jeff Jackson, trades in the kind of punk fervor that inspires teenagers to thrash in mosh pits, raid merch booths, and obsessively listen to the same album. The power of what a few kids and some amped instruments can do is clearly a subject near to Jackson’s heart; not only does he perform in the self-described “weirdo pop band” Julian Calendar, but he’s allowed the vinyl single format to influence the design of the novel itself: Destroy All Monsters features an A-Side—which constitutes the novel proper—and a reverse B-Side, an alternate follow-up to the main story that follows some of the same characters in radically different incarnations. The novel contends frankly with both the difficulties of maintaining youthful passion for loud, distorted noise as one grows older and how the resentments and obligations of adulthood begin to accrue.

To the young, music can be a religion. Destroy All Monsters (357 pages; FSG), the latest novel from Charlotte-based author Jeff Jackson, trades in the kind of punk fervor that inspires teenagers to thrash in mosh pits, raid merch booths, and obsessively listen to the same album. The power of what a few kids and some amped instruments can do is clearly a subject near to Jackson’s heart; not only does he perform in the self-described “weirdo pop band” Julian Calendar, but he’s allowed the vinyl single format to influence the design of the novel itself: Destroy All Monsters features an A-Side—which constitutes the novel proper—and a reverse B-Side, an alternate follow-up to the main story that follows some of the same characters in radically different incarnations. The novel contends frankly with both the difficulties of maintaining youthful passion for loud, distorted noise as one grows older and how the resentments and obligations of adulthood begin to accrue.

Destroy All Monsters centers on the music scene in a “conservative industrial city” called Arcadia. The prologue opens with a memorable performance by hometown heroes the Carmelite Rifles at a show attended by a motley assortment of locals:

The strip-mall goths, the mod metalheads, the blue-collar ravers, the bathtub-shitting punks, the jaded aesthetes who consider themselves beyond category. Everyone in line has imagined a night that could crack open and transform their dreary realities.

Also present at the show are two of the characters who will drive the rest of the novel: budding musician Florian and the forlorn but enigmatic Xenie. Not long after the Carmelite Rifles show, which ripples through the audience’s lives with the impact of an early Velvet Underground gig, a mysterious plague grips the entire country. All around the United States, club patrons are being transfixed by some unknown spell that causes them to gun down or otherwise attempt to murder the bands onstage:

The noise duo at the loft party in the Pacific Northwest. The garage rockers at the tavern in the New England suburbs. The jam band at the auditorium on the edge of the Midwestern prairie. The blue grass revivalists at the coffeehouse in the Deep South. There was never any fanfare. The killers simply walked into the clubs, took out their weapons, and started firing.

Although the killers’ motives remain largely ambiguous (most of them appear to be in a trance-like stupor as they go about their attack) the parallels to recent events are chilling. After terrorist attacks on music venues in Manchester and Paris in the last few years, it is all too easy to imagine the same violence occurring on this side of the Atlantic. The threat of danger feels heightened for the young people at the heart of Destroy All Monsters, to the point that the question of whether or not to perform a scheduled show becomes a matter of life and death for Arcadia’s local acts.

When tragedy ultimately does strike (“The band is heading for the [song] bridge when the first shot is fired”), Florian and Xenie are left to figure out how to privately mourn the loss of a close friend when seemingly everyone in town is doing so in a very public, outsized way. The spat of murders across the country also force Xenie to reckon with the fact that so much of the music playing at local venues and taking up space on her hard drive is, in a word, mediocre. “I used to have a huge music collection,” Xenie relates. “I was obsessed and even saved my concert stubs in a red cardboard box. Sometimes I’d open the box, and just touching the tickets was enough to give me a rush…These days I crave silence.”

Her statement is a lament for an age that has come to be defined by noise, much of it meaningless. Xenie and others in Arcadia’s music scene must grapple with the difficulty of conveying authentic expression in a world drowned out by sound. As Florian contemplates after the last show he’ll ever play: “It’s too easy to transform a moment of truth into a cheap performance.”

Destroy All Monsters understands the impetus to pick up a guitar and strum a power chord, perhaps out of the misguided notion that the result could lead to some change in the world. And the novel understands the disheartening fact that the country is full of numerous small towns like Arcadia, with its dive bars, shuttered factories, and hobo camps, each of them with their would-be punk rockers like Florian. Amid the story’s nationwide epidemic, Jackson’s characters display crucial growth: what ultimately comes to matter—more than selling out concert halls or recording a promising demo—is remaining true to the memory and last wishes of their friends after they’re gone. “Not everything has to be a performance,” Xenie concludes. “Some things should stay pure.”

Jackson, whose prose registers as punchy and acerbic, leading the reader through multiple act breaks and perspective changes with ease, is sincere in his depiction of provincial youth yearning for an escape. In the 21st century, rock ’n roll might not mean as much as it once did, but Jackson has written a fitting tribute to its lingering spirit.