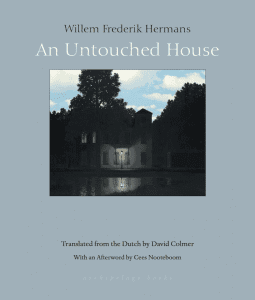

In An Untouched House (115 pages; Archipelago), Willem Frederik Hermans presents a lucid, exhilarating account of a Dutch partisan in the waning months of World War II. Hermans, a premier and prolific author in the Netherlands, penned the novella in 1951, but only now has it received an English translation courtesy of David Colmer.

In An Untouched House (115 pages; Archipelago), Willem Frederik Hermans presents a lucid, exhilarating account of a Dutch partisan in the waning months of World War II. Hermans, a premier and prolific author in the Netherlands, penned the novella in 1951, but only now has it received an English translation courtesy of David Colmer.

The story opens during the final moments of the World War II, with the theme of isolation permeating the narrative. Herman writes, “I didn’t look back. There was nobody in front of me…. I looked back at the others. No one was close enough to ask for water.” A sense of confusion abounds as our nameless narrator finds himself unable to communicate with his fellow soldiers: “Within our band of partisans, made up of Bulgarians, Czechs, Hungarians and Romanians, there wasn’t a single person I could understand.”

His battalion enters a spa town, where he comes across an abandoned luxurious house, replete with amenities, but bereft of human life. This is his escape from conflict, where he can “pretend like the war never existed.” He makes himself at home, takes a bath, and falls asleep, only to be awoken by Nazis ringing the doorbell in search of lodging. The interloper manages to convince them that he is the owner of the house with deft, casual dishonesty.

The next morning he wakes convinced of the lie he imparted on his German visitors: “I the son of the house woke up the next morning to general quiet thinking: I have always lived here. This is my home.”

There is an eerie vacuity to the descriptions of the narrator’s surroundings: “Then I would walk up and down, touching objects without investigating them. On medicine bottles and compacts, on handkerchiefs, and on the edge of the sheets were names I didn’t try to pronounce.”

Throughout the book, the protagonist refuses to allocate names to the other characters, and instead only gives them titles: the colonel, the Spaniard, the Germans. They are not individuals in his eyes; their identities are wrapped up entirely in their countries of origin or military ranking.

Although he is the protagonist, our narrator proves passive and the action of the plot is acted upon him. He makes few decisions. His choice to inhabit the house is the end result of aimless wandering rather than an active search. He soon discovers there is no escape. The architecture of the story reaches its apex as the whirlpool of action spins toward this previously unattended and innocuous building.

The narrator describes the increasingly disturbing events with a detached, passionless voice:

I could clearly see the dead woman. I sat down next to her on the bed and felt her face with my fingertips. It was now cold. I stuck my hand under her coat, under her skirt, and laid it on her thigh. Cold, a thing, water and proteins, something chemists have studied, nothing more.

The narrator possesses only the silhouette of morality, attached to nothing, a vagabond of land and virtue. In the end, his actions prove nearly as cruel as the Nazis themselves. The vastness of World War II becomes a microcosm within this singular building. The house thus feels like not a home, but a mere frame, lacking any moral edifice.

Although An Untouched House is brief, it is worth pacing oneself and absorbing its remarkable density. Hermans is the architect of a masterful story—concise but expansive in vision.