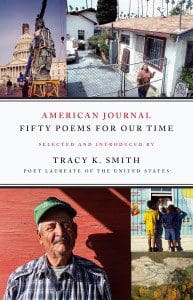

American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time (120 pages; Graywolf) delivers on its promise of introducing readers to some of our most important contemporary American poets, both well-known and emerging. Moreover, the writers featured in it are a reflection of the diversity of the United States, which is what one would hope for in a collection curated by the current U. S. poet laureate, Tracy K. Smith. In addition to featuring a racially diverse group of writers, there are poems by old and young, female and male, and straight and gay poets (although queerness is not a theme that is really explored in it, except in Terrance Hayes’ “At Pegasus”). Clearly, there is a wealth of perspective in this book, making one wonder whether a collection that attempts to appeal to such a broad audience might read as too general or watered down. This isn’t the case.

American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time (120 pages; Graywolf) delivers on its promise of introducing readers to some of our most important contemporary American poets, both well-known and emerging. Moreover, the writers featured in it are a reflection of the diversity of the United States, which is what one would hope for in a collection curated by the current U. S. poet laureate, Tracy K. Smith. In addition to featuring a racially diverse group of writers, there are poems by old and young, female and male, and straight and gay poets (although queerness is not a theme that is really explored in it, except in Terrance Hayes’ “At Pegasus”). Clearly, there is a wealth of perspective in this book, making one wonder whether a collection that attempts to appeal to such a broad audience might read as too general or watered down. This isn’t the case.

The poems in American Journal both celebrate and critique the American “way of life.” There are poignant portrayals of small-town and rural America (not to be confused with white America) in poems like Oliver de la Paz’s “In Defense of Small Towns” and Vievee Francis’ “Sugar and Brine: Ella’s Understanding,” as well as nods to urban America, such as in Major Jackson’s “Mighty Pawns,” a witty poem about a tough and brilliant kid from Philadelphia who “could beat/any man or woman in ten moves playing white.” There are also honest appraisals of our frequent complacency in the face of injustices meted out by our government in Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War” and in Layli Long Soldier’s “38,” which is something of an anti-poem that recounts in a nonlinear fashion the Abraham Lincoln-sanctioned execution of thirty-eight men from the Dakota tribe. Near the beginning of the poem, Long Soldier alerts readers:

You may like to know, I do not consider this to be a “creative piece.”

I do not regard this as a poem of great imagination or a work of fiction.

Also, historical events will not be dramatized for an “interesting” read.

Therefore, I feel most responsible to the orderly sentence; conveyor of thought.

That said, I will begin.

You may or may not have heard about the Dakota 38.

Other poems touch on other relevant social concerns: Tina Chang’s “Story of Girls” and Donika Kelly’s “Fourth Grade Autobiography” speak to our increasing societal awareness of the prevalence of sexual abuse—an awakening facilitated by the #Me Too movement. One of my favorite poems in the book, Eve L. Ewing’s “Requiem for Fifth Period and the Things That Went on Then,” is an intimate and recognizable portrayal of contemporary school life, but I can’t read it (especially its final lines) without thinking about recent school shootings. The poem characterizes several members of this school community, painting an especially vivid portrait of a student named Javonte Stevens:

Sing of Javonte’s new glasses,

their black frames and golden hinges that glint in the sun,

and his new haircut, with two notched arrows shorn above his temples.

Another of the strongest poems in the book, Danez Smith’s “From summer, somewhere,” is a must-read about the police killings of black boys that is written from the perspective(s) of the dead boys. It’s a compact poem packed with power. Here is a couplet from the poem: “history is what it is. it knows what it did./ bad dog. bad blood. bad day to be a boy.”

Elsewhere, universal themes such as familial strife, forgiveness, and death are addressed in poems, such as the highly memorable “Reverse Suicide” by Matt Rasmussen and “becoming a horse” by Ross Gay. In Gay’s poem, which manages to be both down to earth and spiritual—humbling, really—the speaker reflects:

But it was putting my heart to the horse’s that made me know

the sorrow of horses . . .

Feel the small song in my chest

swell and my coat glisten and twitch.

Diverse as they are, the poems in American Journal flow into one another, mirroring the melding of experiences that makes us who we are as a nation. This fusion is partly a result of the poems being grouped into thematic sections. Often, poems on opposite pages, such as Rasmussen’s “Reverse Suicide” and Charles Wright’s “Charlottesville Nocturne,” or Ada Limón’s “Downhearted” and Gay’s “becoming a horse,” address strikingly similar subject matter. It might also have been interesting to juxtapose poems that speak to each other in a different way—that also enact the tensions that are particular to a culture defined as much by similarity as by difference. For example, it might have created a pronounced tension to run Lia Purpura’s “Proximities,” which addresses police shootings, but from a perspective of privilege, next to Smith’s “From summer, somewhere.” As it is, they’re placed far from each other. While this may show the difference in the closeness to danger for each poem’s subject(s), this is a point that may be lost on readers.

Overall, American Journal serves as a strong overview of the poetry of our current moment. And in a time in which the only thing most of us seem to agree on is that we disagree—at a time when our nation is in what esteemed journalist Carl Bernstein has dubbed a “cold civil war”—it is refreshing to read a books that unifies our diverse perspectives.