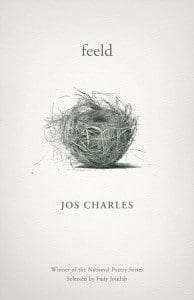

A few days ago, I woke up half-dreaming in the made-up language of Jos Charles’s feeld (64 pages; Milkweed Editions), which is to say I landed softly. feeld –– which is currently longlisted for the 2018 National Book Award in poetry –– challenges the reader to engage with a singular, complex voice (“Chaucerian English [translated] into the digital twenty-first century,” as Fady Joudah notes on the book’s jacket), but one that is also accessible and refined. Throughout the book, which contains sixty short poems, it is evident Charles is a poet who values breath and space. Both aurally and visually, the white space enhances the content, giving the reader time to grasp the meaning of each poem, as well as nearly every line and word. It is a meticulous work; there is nothing rushed or careless in it.

A few days ago, I woke up half-dreaming in the made-up language of Jos Charles’s feeld (64 pages; Milkweed Editions), which is to say I landed softly. feeld –– which is currently longlisted for the 2018 National Book Award in poetry –– challenges the reader to engage with a singular, complex voice (“Chaucerian English [translated] into the digital twenty-first century,” as Fady Joudah notes on the book’s jacket), but one that is also accessible and refined. Throughout the book, which contains sixty short poems, it is evident Charles is a poet who values breath and space. Both aurally and visually, the white space enhances the content, giving the reader time to grasp the meaning of each poem, as well as nearly every line and word. It is a meticulous work; there is nothing rushed or careless in it.

This is not to say one can fully comprehend every layer of feeld: appropriately, Charles leaves plenty of room for interpretation as her wordplay produces a great deal of double entendre. What happens between the words, how words are fused or disjoined, and the sounds they produce—in short phrases, such as “where it tends” in the poem titled “V” and “re member” in “XXXIX”—are as important as the words themselves. In addition, as Stephanie Burt notes in a blurb, Charles’s latest work displays a predilection toward puns. Much of this is accomplished through words—such as “sirfase,” “queery,” and “dicke,” as well as “copse,” “cropse,” and “corpse”—that contain echoes of other words.

Yet the puns in feeld are more tragic than comic. feeld is earnest in the best sense. Since, as the speaker explains in “VII,” there are so many layers to being transgender (and to feeld), when the poems employ directness –– such as in “LIV,” when the speaker laments, “u who unforl me/ how many/ holes would blede/ befor/ u believ/ imma grl” –– it is to devastating effect and causes the reader to pay close attention.

In fact, one of the great pleasures of reading feeld is when we happen across these instances of candor. This occurs again in the final line of the poem “XI,” in which the speaker states, “thomas sayes trama lit is so hotte rite nowe.” At that moment, it is as though Charles had been stretching a rubber band until it was capable of singing a little, but then allows it to snap, producing a powerful resonance.

It’s clear feeld is a book about identity and trauma, but is Charles’s work political? And if she intends to achieve any political aims through feeld, does the prettiness of her writing style soften the impact too much?

The truth, perhaps, is that Charles is an astute poet who has mastered the restraint apparent in well-crafted books of poetry that might otherwise be dubbed (and therefore dismissed) as overly personal or “political”—or, as the speaker puts it in the final line of the poem “XI,” “trendy.”

There are references to political concerns like “masckulin econoymes,” “votes,” and “balots” sprinkled throughout the text, but feeld seems more of an appeal to change at the individual rather than policy level.

While all writers are concerned with language, feeld queers language in such a way that it raises questions about whether what we perceive someone to be is as important as what we call them—and, therefore, how we define their existence. feeld asks us to consider whether existence is in fact defined by naming—that is, by language.