A.M. Homes first made her mark on the literary scene with 1990’s The Safety of Objects, a dark and dynamic collection that established her as one of our foremost chroniclers of suburban dysfunction. Even more astonishing was the fact that Homes wrote most of the stories while still in graduate school. A movie adaptation followed in 2001, but its tacked-on ending—featuring the book’s assortment of characters all grinning warmly for the camera at a backyard barbecue—felt disingenuous. Homes’s stories are rarely the kind where troubles can be resolved with group therapy sessions or summer cookouts; her method is much closer to the couple who set their house ablaze at the start of her novel Music For Torching: sometimes in order to free yourself from the trappings of modern life, you have to burn it all down.

A.M. Homes first made her mark on the literary scene with 1990’s The Safety of Objects, a dark and dynamic collection that established her as one of our foremost chroniclers of suburban dysfunction. Even more astonishing was the fact that Homes wrote most of the stories while still in graduate school. A movie adaptation followed in 2001, but its tacked-on ending—featuring the book’s assortment of characters all grinning warmly for the camera at a backyard barbecue—felt disingenuous. Homes’s stories are rarely the kind where troubles can be resolved with group therapy sessions or summer cookouts; her method is much closer to the couple who set their house ablaze at the start of her novel Music For Torching: sometimes in order to free yourself from the trappings of modern life, you have to burn it all down.

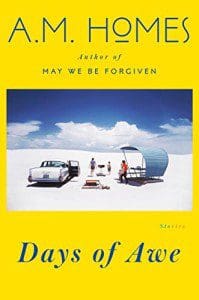

Despite recent accolades, including the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2013, Homes’s output has become less frequent as of late, and perhaps hasn’t achieved quite the same impact as her earlier work. Thus, the time seems right for her latest story collection, Days of Awe (304 pages; Viking), as it presents a chance for readers new and old to check in with this prominent voice in transgressive literature. The book gathers from a wide range of material, opening with “Brother on a Sunday,” which first appeared in the New Yorker in 2009, and includes “The National Cage Bird Show,” the only story original to this book. Coincidentally, those are two of the strongest pieces in the collection.

“Brother on a Sunday” is a case study in the elements Homes does so well, from the crisp minimalism of her prose to her off-kilter depiction of suburban ennui. The story concerns a successful plastic surgeon named Tom and his wife’s vacation to the Hamptons with their wealthy friends, the impending arrival of the protagonist’s uncouth older brother serving as an ominous storm gathering over the weekend. Homes mines this material for both dark comedy––Tom’s friends are constantly backing him into corners at parties, asking for his medical opinion of their unsightly rashes or moles––and an unexpectedly poignant commentary on aging. Tom’s musings on the recent death of a friend prove doubly effective due to Homes’ measured tone:

The men seem oblivious to the inevitability of aging, oblivious to the fact that they are no longer thirty, to the fact that they are not superheroes with special powers. He thinks of the night, a year ago, when they were all at a local restaurant and one of them went to grab something from the car. He ran across the road as though he glowed in the dark. But he didn’t. The driver of an oncoming car didn’t see him. He flew up and over it. And when someone came into the restaurant to call the police, Tom went out, not because he was thinking of his friend but because he was curious, always curious. Once outside, realizing what had happened, he ran to his friend and tried to help, but there was nothing to be done. The next day, driving by the spot, he saw one of his friend’s shoes—they had each bought a pair of the same kind the summer before—suspended from a tree.

“The National Cage Bird Show” hones in on the unexpected friendship that develops between a troubled 13-year-old girl in New York and a U.S. soldier deployed in the Middle East. The two of them converse exclusively through a chat room for parakeet lovers, the transcript of which comprises the entirety of the story. This form allows Homes to examine both the harrowing, Hurt Locker-esque experience of soldiers in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan (“I am the local EOD, explosive ordinance disposal specialist, basically the Maytag Man for bombs. I’m good with my fingers. I can thread a needle in the dark. Anything with a detonator, I’m your man”) as well as the particular sadness of being a teenage girl: “Is it weird to say I just wish things could be the way they were? I wish I didn’t know that a dad could fall out of love with his family. Part of me refuses to believe it—does that make me a romantic?”

The combination of the two proves oddly touching, and maintains a sense of innocence for the duration of the story, despite Homes’s longstanding penchant for the taboo. The backdrop of a bird lovers’ chat room provides the story with a humorous grounding, but also underscores how the Internet has increasingly become the main outlet of personal connection for those, likes Homes’ characters, who identify as outsiders.

“A Prize For Every Player,” another standout from Days of Awe, originally appeared in a book of photographs by acclaimed Bay Area artist Bill Owens. Homes may feel a kinship with Owens, as his work similarly traces the lives of everyday Americans, capturing the candid moments in their kitchens or yards. The surreal “Player” follows a nuclear family on their weekly shopping trip, only this family has turned such consumerist ventures into their own little game show, with the husband and wife scanning the aisles with dual shopping carts in search of the best deals.

The absurdity reaches almost Kafka-esque levels once the family stumbles upon an infant left abandoned in the store (“Can I get it?” the daughter asks. “Can I, can I? It can be for my birthday and Christmas and everything else, too”) and later when the husband is nominated as a presidential candidate by the crowd in the electronics department. Though the story is a decade old, his impassioned speech brings to mind the populist rhetoric that has become increasingly prevalent in Western politics:

The point is, I remember America. I remember when politicians had a vision, a dream for the people of this country, and didn’t run their campaign based on a tax rebate if elected—essentially attempting to buy the vote. Are we that gullible that we thought George Bush’s three-hundred-dollar rebate would cover it? Think of what that vote cost, think of your retirement account, your health insurance, your mortgage, and your cost of living versus your salary. How much did you lose, and how much did you make?

Not all of the stories in Days of Awe tap such a rich vein of social commentary. “Hello Everybody” and “She Got Away” trace the trials and tribulations of the same well-to-do Southern California family, territory well-trod by Bret Easton Ellis in the Eighties. (“What kind of doctor wants a pregnant woman to lose weight?” “A Beverly Hills doctor” is a representative exchange.) But the book still frequently finds Homes at her best. Her fiction ushers our American landscape into a literary funhouse, commenting with acerbic wit and deft characterization on the distorted reflection that appears. Days of Awe is a reminder that we are lucky to have her singular talent.