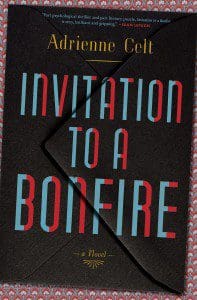

Adrienne Celt’s Invitation to a Bonfire (256 pages; Bloomsbury) is a novel delightfully unconcerned with passing literary trends. Celt has her eye trained on the past, on both the esteemed literary works that have influenced her and the massive social upheaval that was the Russian Revolution. Invitation to a Bonfire opens on the young Zoya Andropova, an orphan of the Revolution who makes her way to safety in the United States only to become the victim of petty cruelties at New Jersey’s prestigious Donne School. Zoya observes the strange customs and practices of American culture while finding solace in tending to the school’s greenhouse.

Adrienne Celt’s Invitation to a Bonfire (256 pages; Bloomsbury) is a novel delightfully unconcerned with passing literary trends. Celt has her eye trained on the past, on both the esteemed literary works that have influenced her and the massive social upheaval that was the Russian Revolution. Invitation to a Bonfire opens on the young Zoya Andropova, an orphan of the Revolution who makes her way to safety in the United States only to become the victim of petty cruelties at New Jersey’s prestigious Donne School. Zoya observes the strange customs and practices of American culture while finding solace in tending to the school’s greenhouse.

As the years pass, Zoya finds herself at the center of a bitter love triangle between a bestselling Russian writer and his wife, a couple who may or may not bear a passing resemblance to Vladimir Nabokov and his partner, Vera. This shift in the book’s storyline does not go unnoted, as Celt transitions from boarding school bildungsroman to the high suspense of a vintage Patricia Highsmith novel. Recently, Celt, whose story “Big Boss Bitch” appeared in Issue No. 107, talked to ZYZZYVA about her literary influences, including Nabokov, as well as her interest in Russian history and what it means to “be American.”

ZYZZYVA: So much of the style and milieu of this novel, from its period setting and incorporation of epistolary elements, put me in mind of classic works of fiction rather than any contemporary peers. Both the writing and life of Vladimir Nabokov register as a clear influence, and I was also reminded of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day. Perhaps you could talk about some of the novels that inspired Invitation to a Bonfire. Did you envision this novel in conversation with those works?

ADRIENNE CELT: Remains of the Day is one of my favorite books, and although I can’t say it was an intentional influence on Invitation, I’m gratified to be considered in conversation with it. And I can certainly see the resonance: both are steeped in yearning for a time gone by, and both offer narrators whose unreliability comes less from a desire to mislead, and more from a desire to cling to their fracturing past, the things they once knew to be true. So maybe it was there without me knowing. God knows a lot of books must have left that kind of subconscious impression.

In terms of novels I turned to specifically, you’re right that the spirit and tone of this book are first and foremost inspired by Nabokov, particularly Lolita, Pale Fire, and Pnin (and of course the title is a hat-tip to Invitation to a Beheading.) I also re-read Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, which is maybe more contemporary than your question suggests, but arguably just as haunted by romantic notions of the past. Mostly, with that book, I was interested in how much personal history a narrator could offer, especially early on, without causing the plot to drag—Tartt does an incredible job of folding Richard’s backstory into his motivations and his moral character, and I definitely had him on my mind.

Beyond that, maybe some Patricia Highsmith? Maybe some Jean Rhys? I read both those writers while working on my early drafts, and I borrow a sense of propulsion and atmosphere from both of them.

Z: The first part of the novel is largely concerned with Zoya’s journey to America following the violence of the Russian Revolution, which you capture in particular detail. What kind of research was involved in writing about that period of history?

AC: One of my college majors was Russian (the other was philosophy), which meant I had a basic understanding of the Russian Revolution already at my fingertips when I began—and I think it’s worth mentioning that some of that education took place in St. Petersburg, so I wasn’t drawing purely on American attitudes and culture. I hope that makes a difference. Of course I didn’t remember all the dates and specifics perfectly, so I went back and made an outline of the various smaller revolutions that finally led to the collapse of the aristocracy and the rise of the Soviet Union, which I cross-referenced with a calendar of my character’s birthdates and major life events. Honestly, a lot of my research for this book was purely checking dates, and making sure I wasn’t being too anachronistic—which is as true for events that took place in America as in Russia.

People who have never written historical novels, I think, might be surprised which pieces actually have to be deeply researched: it’s so often the little things. There were big patches I could sort of feel my way through by instinct, but when I wanted to figure out what kind of flooring would plausibly be in a Russian apartment, I checked with my college Russian professors, because a guess didn’t feel good enough. There are also, of course, historical novelists who get much more into period-specific detail than I do: I work from a place of character first, and fill in the details as necessary.

Z: As much as Zoya’s struggle is rooted in her experiences as an orphan of the Russian Revolution, a great deal of her story felt universal to me; she is the quintessential outsider, and I think anyone who has ever felt ostracized or different from others would relate to her experiences in boarding school. “Things can go ugly fast,” her confidante Hilda states. “People can be ugly,” and we see this at the Donne School. The first part of the book follows Zoya as she observes her fellow students in an attempt to her learn what it means to “be American.” What made you want to write about the concept of “being American” from the perspective of an outsider to the American experience?

AC: I wanted to write about “being American” from an outsider’s perspective because I think we often don’t understand that there is an “outside.” We think that the American point of view is all there is. (Not that provincialism is unique to our country, but we’ve always been a little extra about it.) When you have an outsider looking at something—a culture, a philosophy, a way of life—you’re forced to recognize that it’s not inevitable. America, as it exists, is not inevitable. That’s kind of a radical thought, but also totally natural and obvious.

Zoya is a wonderful avatar for exploring this, because she’s rarely been an insider in any system. So, while her alienation is sincere, her use of cultural norms becomes a kind of game, or experiment. After a while, she realizes that if an arbitrary system of rules is deciding what’s “morally good”—and different systems decide to attribute “good” to different things—then maybe “moral good” doesn’t have any inherent meaning. Maybe satisfaction can be a moral good. Maybe love can.

Z: Speaking of the parts of the novel, there is a distinct shift that occurs as we move into the second part, in which the novel takes on some suspense leanings, almost operating in the genre of Highsmith. Was there a conscious decision to change the tone and direction of the novel halfway through, or was that something that seemed to happen organically during the writing process?

AC: Ha! So my name-check of Patricia Highsmith has come back around.

The shift was organic. In the original drafts, the first section was shorter, because I wanted to get to the suspense more quickly. But I’m always fascinated by how people come to themselves—how identity is formed over time, through experience and decision-making—which means I’m always going to be invested in giving my characters fleshed-out lives.

I also think that the two parts need each other: the second half wouldn’t operate the same way without the slower burn of the novel’s first section. Learning who Zoya, Lev, and Vera are as people teaches you a lot about what they truly want, and what they might be willing to do to get it. Once you understand someone’s desires, you can see the stakes of their actions more clearly. Plus you attach to them with greater tenderness.

Z: You raise such a fascinating idea in this novel––both Zoya and Vera seem to argue that sometimes an artist needs to be saved from themselves; that perhaps custodians of an artist should prevent certain works from being let out into the world in order to preserve an artist’s legacy. As someone who often finds himself drawn to the messy, more personal films or novels that lead to artists receiving a critical drubbing, this is a thought I love pondering. Have you ever wished, even fleetingly, that an author’s readership could be the guardians of their body of work?

AC: Really, who is the guardian of an author’s legacy if not their readers? I’m not saying I agree with the lengths that Zoya and Vera go to, as an example for the average person—they definitely take “protecting someone from themselves” to new heights. But all books become, in a sense, the property of their readers once they’re published.

On the other hand, if you’re asking whether writers should allow their readers and critics to direct the course of their career, I would say no. I do believe in having sensitivity to the reader’s experience while you write, but not in trying to please everyone. It’s a losing battle, for one thing, and—as you point out—it can scare artists away from making their most personal, groundbreaking work.

In the end, it’s more important to bend towards instinct than popularity.