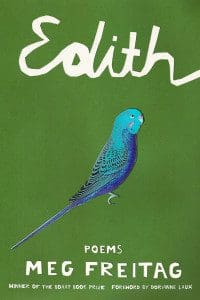

Meg Freitag’s Edith (83 pages; BOAAT Books), winner of the inaugural Book Prize from BOAAT Press, comprises a series of vivid, voice-y lyrics addressed to a pet parakeet—the titular Edith—who dies halfway through the book. It turns out speaking to a pet bird makes a certain kind of affectionate disclosure possible; the experience of reading these poems is often one of overhearing an earnest speaker struggling to explain herself to a tiny, mute beloved. But the speaker’s love for her pet is also inextricable from her tenderness toward the world, and her mourning for Edith is bound up in other losses, too, including the end of a relationship, a transcontinental move, and the deaths of friends and idols.

Meg Freitag’s Edith (83 pages; BOAAT Books), winner of the inaugural Book Prize from BOAAT Press, comprises a series of vivid, voice-y lyrics addressed to a pet parakeet—the titular Edith—who dies halfway through the book. It turns out speaking to a pet bird makes a certain kind of affectionate disclosure possible; the experience of reading these poems is often one of overhearing an earnest speaker struggling to explain herself to a tiny, mute beloved. But the speaker’s love for her pet is also inextricable from her tenderness toward the world, and her mourning for Edith is bound up in other losses, too, including the end of a relationship, a transcontinental move, and the deaths of friends and idols.

This intimate address is only part of what makes Freitag’s speaker so endearing. She’s also winningly imaginative, once comparing heartache to an elaborate pinball game, and standing beneath a glowing sky to being “inside / A plum … some needful giant / Was holding a flashlight to.” In a scene typical of Freitag’s dizzying dream sequences, the speaker is “walking around Costco / Without any skin on while a throng of people / Followed [her], clicking those little devices / Which are meant for training dogs / Every time [she] touched something.” The book is also carefully, almost novelistically structured; while we know from the get-go Edith is doomed, the events of her death reveal themselves with suspenseful, dilatory slowness.

Long before the book’s publication, my friends and I read and circulated all the poems of Freitag’s we could find online, gushing about their luminous nouns, their surprising swerves, and their unspooling epic similes, which manage to precisely characterize our mushiest, most interior experiences. Who hasn’t watched their lover from across the room “like a snake / With its eye on a prairie dog’s / Hole?” Who hasn’t, in the throes of dread, felt “all the blood / Moving through [them] with great / Effort, like it was full of seeds?” In the following interview, conducted over email, Freitag discusses how exactly images like these occurred to her, as well as mirrors, dreams, and writing by ear.

ZYZZYVA: The majority of these poems are addressed to Edith, who we learn is the speaker’s pet parakeet. Over the course of the book, I feel like Edith evolves from a mourned pet to a sort of emissary from the afterlife; speaking to Edith becomes a way of speaking to the dead, or to the void, or to an indifferent god. What drew you to this kind of highly lyrical, odic apostrophe?

Meg Freitag: I’ve always been really interested in recurring characters in poetry collections. John Berryman’s Henry, Bill Knott’s Naomi, Herbert Zbigneiw’s Mr. Cogito, for instance. At the time when I started the Edith poems, I was reading Josh Bell’s No Planets Strike, which is a wonderful and bewildering book. He uses the name “Ramona” like a touchstone in his poems. No matter how wild they get, he’s able to pull the poem back to its center with just three syllables.

When I first started writing to Edith she was still very much alive. I had no idea the turn things would take. The Edith poems started as a kind of exercise, a way to lighten up my writing a bit and hopefully generate more material for workshops. Edith and I had been through a lot together over the years, and I was taken with this idea that she’d been passively complicit in it all through witness. I was still searching for my “voice” at that time. When she died about six months into the project, the whole project immediately took on a new significance. I don’t know that at any point during the writing process I thought about the Edith poems as eventually comprising a book with a cohesive emotional arc, with a sort of composite narrative. This is something that only really revealed itself to me when I was putting the book together. During the writing of the poems, I just had this feeling that I followed through its evolution and eventual natural conclusion. It was all very organic for me.

Z: It seems these poems are also really concerned with narratorial unreliability. The speaker repeatedly confesses to “lying,” which I imagine must be an interesting preoccupation for a writer so given to elaborate, sometimes hyperbolic figuration. Can you talk a bit about the poems’ obsessions with both fact-bending and truth-telling?

MF: I love the idea of playing around with “truth” in a poem because of how natural it is for readers to assume the events that take place in poems—particularly poems that confess to transgressions or poems with a more coherent narrative bent—are entirely autobiographical. To explicitly draw attention to the fact that there is any such thing as a truth or an untruth in a poem is destabilizing in a way that returns a sense of autonomy to the speaker. Though many of the things that take place in the book, including the central story of Edith’s death, are based on actual events from my life, I wanted to give the speaker of these poems a life and voice of her own, and calling attention to her “lying” occasionally was one of the ways that I facilitated this.

Z: Speaking of figuration, your images are just so crystalline and arresting: “a post-apocalyptic / Waterpark”; “A hundred of my own heads on wooden stakes, / But…tiny, like a tray of hors d’oeuvres”; “the sight of a glass of goat’s milk / Glowing blue in approaching headlights.” How do these images usually arrive for you, and does a particular image usually inspire or nucleate a poem?

MF: There’re so many different ways I arrive at images. It’s not uncommon for me to pull images from dreams I’ve had; for instance, like that tray of terrible hors d’oeuvres. Sometimes it’s really just as simple as that.

But more commonly the most compelling images will begin to develop once the poem is rich enough that it’s like a world I can step into. I’ll manage to sort of unlatch from my sense of physical body and environment and I’ll step into the poem and walk around, pick things up, smell the smells, taste the tastes. I’ll examine the texture of the light, the colors, the quality of the air, the background noises. And then I’ll let my subconscious and imagination do the heavy lifting through associative exploration.

I’m also very preoccupied by the music of a poem, the way the sounds of words change depending on where you place them in relation to each other. It’s not uncommon for my “ear” to follow an idea to the end of itself separate from any sense of reason. The glass of goat’s milk glowing blue is a perfect example of that type of figuration.

Z: Relatedly, I felt so consistently surprised by where each poem ended up. While the poems often build in a way that seems causal or narratively connected at the level of the line—and while there’s always a vital emotional linkage between the opening and closure of a poem—the endings always felt totally and thrillingly unforeseen. I’m wondering if you have an idea of the territory a given poem will cover when you start writing it? And how do you sense when it’s raveled to a stopping-point?

MF: It really depends! I think I always know in the very back of my head to some extent, but the practice of writing a poem is a journey for me. Often my first drafts are more or less entirely stream-of-consciousness. I get a lot of enjoyment and creative momentum out of engaging with a thought far past what might seem like the natural conclusion. You end up in a lot of surprising places this way. But it’s also a delicate mechanism. If you get too far away from the purpose of the poem, there’s a feeling like someone playing a chord out of tune on a guitar. The editing process, for me, is largely about reining in the wackier elements. Tuning the instrument of the poem.

Z: I’m so interested in how this book found its way into being. Which is the oldest poem in this book, and which the newest? What changed in your life between the writing of the first and the last?

MF: Probably the most significant thing that happened for the purposes of the book is the death of Edith. But there were also two cross-country moves in there, the rise and fall of a couple meaningful relationships, the death of my oldest childhood friend, and I began and finished my MFA. Lots of other stuff, too.

The oldest poems in the book are “Course in Miracles” and “Tender the Wing.” These poems were written as part of my writing sample when I was applying to MFA programs back in 2012. The oldest “Edith” poem included in the collection (there were a couple earlier ones that ended up on the cutting-room floor) is “How to Make a Horror Movie Without Any Hands.” I wrote that on a plane during my first month of grad school. I woke up from a nap dream with the image of the dead whale in my head and the entire poem just came gushing out of me. It was a big moment for me, writing that poem. I had been looking for that voice for a long time, and there it finally was.

It’s hard to say what the newest poem in the collection is, as I’m often working on many poems simultaneously over a long period of time. I think it’s perhaps fair to say that “Poem for Meg” is the youngest poem in the collection, all things considered. That was the last one I was working on till the very end, right up until the week before publication.

Z: On that note, can you talk a bit more about the development of the voice in these poems? This book has such a distinctive quality of vocalization. How did you conceptualize and light upon your particular narratorial style?

MF: It was a long time coming. I feel like I’d grown up mimicking the style of poetry I’d cut my teeth on: Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Robert Hass, Robert Lowell, a bunch of others. All truly wonderful poets, but poets of a different era. I would once have cringed to let something like an iPhone or Diet Dr. Pepper into a poem. It’s funny to think about that now. I learned so much this way, writing poems in older traditions and modes. I think there’s a lot to be said for imitation as a way of teaching oneself how to write well.

Taking a workshop with Dean Young my first semester of grad school was a big turning point for me. He’s such a playful, fearlessly unconventional poet. But you read half a poem of his and you realize right away how seriously he takes his craft, how brilliant he is. His teaching style is not dissimilar. He doesn’t allow critical or prescriptive comments in his classes, only descriptive. And he’s very encouraging of wildness, which was freeing to me. It felt like a safe space to experiment without worrying about being seen as a less serious poet, which is something I think I was once worried about. It took a little playing-around, but when I landed on the “Edith” voice, it just really clicked. I had so much energy for those poems.

Z: Whom were you reading when you wrote this book? What films and music were you swimming in? Who are the other godparents of Edith?

MF: Oh, gosh. Where to start? Please accept my preemptive apology for how long this is going to be. First of all, I should explain that my two favorite movies of all time are Tarkovsky’s Mirror and Die Hard. To see Edith as possibly a strange love child of these two creative masterpieces is maybe a good starting point.

There were a few books I read for the first time or returned to during the Edith days that particularly resonated with me. It’s always so hard to remember them all, but the list definitely includes Sylvia Plath’s Ariel, Larry Levis’ Winter Stars, Jack Gilbert’s The Great Fires, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, Emily Kendall Frey’s Sorrow Arrow, Lord Alfred Tennyson’s In Memoriam, Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market, Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s Song, Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red and Beauty of the Husband, Ariana Reines’ Cœur de Lion, Frank Stanford’s The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son and The Name of the World, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Lorrie Moore’s Self Help, James Welch’s Winter in the Blood, etc.

Music is a little trickier. In my younger life, music was incredibly important to me. I was in a band, I sang and wrote songs, I listened to music all day long. I went to three to four shows a week. My laptop was actually stolen partway through writing this book. All the music I’d saved over the course of my entire life went with it. The manuscript was close to finished at that point and the loss of my laptop set me back about a year—so much material I hadn’t saved. It was devastating, though I think ultimately the book was better for it. But for this reason a lot of Edith was written in silence. It broke my heart to listen to music for a little while after that loss.

A couple songs or albums I remember being obsessed with include Uncle Tupelo’s cover of “Now I Wanna Be Your Dog,” Wye Oak’s “Civilian,” The National’s High Violet, Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” and “Running Up That Hill,” The Antlers’ Kettering, Xiu Xiu’s Fabulous Muscles, Daughter’s His Young Heart EP, The Shivers’ “L.I.E.,” Deer Tick’s solo acoustic stuff, Edith Piaf’s entire oeuvre always and forever.

Z: And there’s that wonderfully apt Edith Piaf epigraph that starts off the book, which translates to “Formerly you were breathing the golden sun. / You were walking on treasures. / We were tramps. We were loving songs.” I love that as an introduction to the book; it so perfectly sets the tone.

On a structural note, how did you choose to divvy up the book into four sections?

MF: The order of the book came somewhat naturally. I labored over it at first but it all fell into place pretty easily in the end. I wanted the book to tell a story, but not too directly. A lot of it ends up being just chronological for this reason, but not all of it. It felt a little to me like looking at one of those Magic Eye pictures. I had to sort of turn my reasoning mind off and look past the poems in order for a shape to emerge. I trusted the feeling and followed it.

Z: And how did you decide to capitalize the beginning of every line, even when enjambed?

MF: Capitalizing the beginning of each line was something I was really drawn to long ago in Olena Kalytiak Davis’ work. I like that it makes each line of a poem into an individual unit. I’ve been doing it with my own work ever since.

Z: How long did it take you to write the book, and how long to find a home for it?

MF: Altogether, the book spans around seven years. It took about 2.5 years for it to find a home with BOAAT, which is actually not a terribly long time to place a first book, but it felt like a million years.

I was standing in line at Trader Joe’s when I got the email from BOAAT. It was totally surreal. I got so shaky that I almost dropped my shopping basket. It was a really good night.

Z: What’s next for you, creatively? Has your work changed post-Edith?

MF: Oh gosh, good questions! I have a few different projects I’m working on currently, both poetry and fiction, and some hybrid stuff. I do think my work is changing. I have less time to write now, which inherently changes the nature of the work. A lot of the poems in Edith were written in maniacal 15-hour stretches. Now it’s more common for me to write in 30-minute blocks, so a lot of the work of a poem is done in my head when I’m not actually writing. I store up a lot of disparate stuff, so there’s a proclivity for denseness in my newer work that I’m having to learn to mitigate.

I’ve also grown out of the Edith voice a bit, thankfully. I’m deeply proud of the collection, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t take a toll on me, holding that hyper-self-critical mirror up to myself all the time as a means of creative generation.