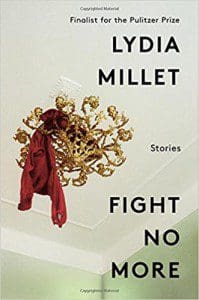

In “Libertines,” the opening story of Lydia Millet’s Fight No More: Stories (211 pages; W. W. Norton), the reader is introduced to a paranoid real estate agent, who becomes convinced that a prospective buyer is an African dictator. At one point, this supposed dictator (who is, in fact, a musician) randomly attempts to commit suicide by falling into the property’s pool.

In “Libertines,” the opening story of Lydia Millet’s Fight No More: Stories (211 pages; W. W. Norton), the reader is introduced to a paranoid real estate agent, who becomes convinced that a prospective buyer is an African dictator. At one point, this supposed dictator (who is, in fact, a musician) randomly attempts to commit suicide by falling into the property’s pool.

So yes—it’s an intriguing, albeit slightly discombobulating start for Millet’s first story collection since Love in Infant Monkeys, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize

This sense of the bizarre and frequently surreal pervades the entire book: in “The Men,” a variation on the traditional Snow White tale, Delia’s husband leaves her, and in his wake, seven dwarves move in, ostensibly to take care of her. The same real estate agent from “Libertines,” Nina, must contend with a vampire client who stores human blood and dead animals in the refrigerator in “I Knew You in This Dark.” Elsewhere, “I Can’t Go On”––arguably the most shocking and satirical story of the collection––propels the reader into the mind of a pedophile who blackmails his step-daughter into sleeping with him.

Unlike many books, the strangeness consistent throughout Fight No More also seeps into the reader. I felt slightly off-kilter while reading, as though the dream-like air, smothering heat, and irrationalities of orderly suburban L.A. (where the collection is set) were warping the stories into mirages.

What grounds these works of fiction and gives them momentum is the diverse cast of recurring characters. Jeremy, the son of a depressed mother and of a re-married father who stingily provides for him, initially comes across as the familiar Rebellious Teen in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” from his passion for Sid Vicious to his explosive acne. Throughout the stories, however, his apathetic persona falls away to reveal someone capable of profoundly caring about others. In a moving attempt to humor Lexie, who asks Jeremy to accompany her and her mother in buying an urn for her recently deceased and sexually abusive step-father, Jeremy jokes, “Sure. I’m solid on urns. Done a lot of urn shopping. I can tell a premium urn from a piece-of-shit urn. It’s all in the seams. Gotta hold them up to the light. You ladies need my expertise.”

Even Paul and Lora, though they never transcend their stereotypes as Jeremy’s uninvolved dad and vacant step-mother, are described with evocative accuracy. Aleska, Paul’s Holocaust scholar mother, ruefully regards her son as someone who “set great store by appearances . . . He’d been embarrassed by the sight of human weakness since he was a teenager.” Lora, on the other hand, “was warm, so nice you felt guilty, and full of just about nothing. For her it wasn’t that history had faded but that it had never existed to begin with.”

Millet allows her characters their small neuroses and gives permission for their thoughts to meander: Jeremy compulsively reaches for Latin phrases (my favorite: Cadavera vero innumera, or “truly countless bodies”), while Nina sees a monk smoking and considers for the duration of a page how someone who has achieved enlightenment could financially support themselves. Millet continually presents a contrast between her realistically drawn characters and the odd, almost absurd situations they are entangled in.

By the end of the last story in the collection, “Oh Child of Earth,” the reader is left with a sense of the absurd and often meaninglessly cyclical nature of life. In it, Aleska goes for a walk, passing “each house in turn, each gate, each privacy hedge or showy rock garden, but as she passed them she also passed nothing at all. They were different and the same: she moved and did not move. What was ahead was past.” Nina, too, feels the noose of the past tightening after her fiancée dies in a freak accident: “Before Lynn, it was true, she’d had only the vaguest sense of her future, but then the future had arrived. Now it was past.” Indeed, in “Those Are Pearls,” Nina is reminded of how she and Lynn met (over the unconscious body of Lynn’s bandmate who attempted to drown himself) when she stumbles upon an officer who is wounded in an alley. For Nina, a crucial event in her life has literally cycled back.

But Fight No More does not inspire a sense of hopelessness or disgust. Despite life’s cyclical nature—or perhaps because of it—we can, and absolutely must, try to do better next time. (Remember, we are in L.A., where everything from the perpetual sunshine to Hollywood’s Dream Factory encourages self-creation and, more importantly, self-re-creation.) When Aleska, whose entire family perished in the Holocaust, and who has devoted her life to studying and raising awareness of its atrocities, reads a study that “54% of Russians now believe he [Stalin] was a wise leader who led the nation to prosperity . . . She sat there for a minute. Helpless. Then picked up her cell, called Lora to come back.”Aleska’s heartbreak catalyzes into a request that her daughter-in-law, Lora, partially pay for the family’s caregiver Lexie’s college tuition. Aleska also leaves a portion of her own money to Lexie in her will. While Aleska’s trail of essays and research has probably accomplished little in breaking the historical and international cycle of genocide and faulty collective memory, she can at least help break the cycle of poverty and violence Lexie is trapped in.

Fight No More is about many things: the ways parents intentionally and unintentionally hurt their children; the anger and hurt from being abandoned by loved ones; how history, both private and public, can become repetitive and inescapable. These issues could have easily overwhelmed and burdened the collection. But because her characters are so distinct, almost startling in their richness, Millet is able to explore such grand questions organically and humorously, all while not taking life too seriously –– and reminding the reader to do the same.