March represents Women’s History Month and, as such, we thought we would share a brief overview of some of the women we’ve been reading as of late, which includes a group of authors operating within a myriad of genres and hailing from a number of locales. We hope this collection serves as just a small sampling of the dynamic work being done by women in literature and non-fiction today.

March represents Women’s History Month and, as such, we thought we would share a brief overview of some of the women we’ve been reading as of late, which includes a group of authors operating within a myriad of genres and hailing from a number of locales. We hope this collection serves as just a small sampling of the dynamic work being done by women in literature and non-fiction today.

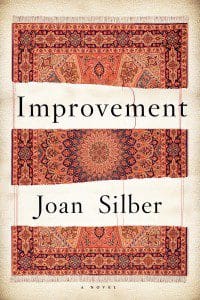

Laura Cogan, Editor: “No one knew the real story but me,” declares one of Joan Silber’s exquisitely drawn characters near the end of Improvement. It is both a brag and a burden this character bears—and a not-quite-accurate statement. Silber has crafted a book that uses a kaleidoscopic narrative technique to meditate on the recurring patterns within our life stories, and the unexpected junctures where our shifting patterns of desire and deception interact with the equally complex lives of others. The frustrating truth of life, beautifully evoked here as only fiction can do, is that not one of us can ever know the real story (if by the real story we mean the whole story). As desperate as we may be to see more, and yet more, our perspective is inescapably blinkered. Still, there are authentic truths in the fragment of the whole that each of us calls our life story. Fiction can remind us of this persistent limitation—remind us of all we cannot know of the lives of others, and that knowledge in turn can, crucially, remind us to remain curious, questioning, empathetic.

Laura Cogan, Editor: “No one knew the real story but me,” declares one of Joan Silber’s exquisitely drawn characters near the end of Improvement. It is both a brag and a burden this character bears—and a not-quite-accurate statement. Silber has crafted a book that uses a kaleidoscopic narrative technique to meditate on the recurring patterns within our life stories, and the unexpected junctures where our shifting patterns of desire and deception interact with the equally complex lives of others. The frustrating truth of life, beautifully evoked here as only fiction can do, is that not one of us can ever know the real story (if by the real story we mean the whole story). As desperate as we may be to see more, and yet more, our perspective is inescapably blinkered. Still, there are authentic truths in the fragment of the whole that each of us calls our life story. Fiction can remind us of this persistent limitation—remind us of all we cannot know of the lives of others, and that knowledge in turn can, crucially, remind us to remain curious, questioning, empathetic.

With a light touch, Silber’s novel offers insights on imitation vs. authenticity; the power and limitations of love; and the cons we run—on each other, and on ourselves. The book is packed with seekers and wanderers, cheaters and dreamers who tell themselves and others little lies to get by. Through their stories, Silber develops a graceful and moving meditation on the idea of reparations and amends. Improvement evokes the beauty and unexpected generosity of our imperfect, inadequate gestures of remorse, our struggle to manage our guilt, and human empathy in the face of irreducible loss—on both a historic and a personal scale. As another character observes, “That was the question asked every day, all over: how much could ever be fixed?”

Improvement is so accomplished and polished that I suspect it will invite many readers to simply sit back and enjoy being in the presence of a fabulous storyteller. But others may pause from time to time to marvel at Silber’s skill, and for any of these readers who close the novel with a sense that they would love to hear Silber discuss craft there is The Art of Time in Fiction, from Graywolf’s excellent “The Art of” series. Here Silber brings similar clarity to complex material, and it’s a pleasure to follow her discussion of works by Chekhov, Flaubert, Baldwin, and Munro, among others.

Speaking of clarity: if anyone you know is still struggling with the very concept of feminism, perhaps We Should All be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie would be an excellent gift, and tonic. While this short essay is unlikely to advance the understanding of those already conversant in the basic terms and ideas of feminism, it may well be gentle and focused enough to persuade those who genuinely have not thought such ideas through but have been susceptible to the noise of misogyny and the often invisible prevalence of sexism. This is a time in which we must ask difficult questions without obvious answers; one such question might well be, “How much can ever be fixed?” Another is certainly: How can we effectively change minds, and advance ideals of equality?

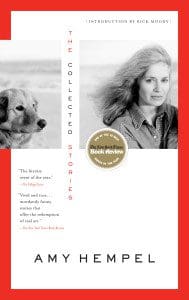

Samantha Aper, Intern: The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel has lived next to my bed since the moment I picked it up three years ago. Reading these stories has been a slow process, as I often find myself putting the book down to stare at the ceiling and turn Hempel’s sentences over in my head. I have told anyone who will listen: you must read this book. Hempel is one of those writers who makes you throw your hands in the air as you question everything you ever thought you knew about fiction. Each word she writes is precise, each punctuation mark carefully chosen. Embedded in these pages are life lessons without the in-your-face siren that says: this is a lesson, pay attention! And when she doesn’t offer a lesson, Hempel writes from a place of hindsight. Her stories make you crawl into another body’s world and live in it as if it were your own. Perhaps what makes her so special is her understanding of the human experience— of the emotions behind the choices people make. She excavates identifiable scraps of experience that leave you somewhere between laughter and tears — typically both.

Samantha Aper, Intern: The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel has lived next to my bed since the moment I picked it up three years ago. Reading these stories has been a slow process, as I often find myself putting the book down to stare at the ceiling and turn Hempel’s sentences over in my head. I have told anyone who will listen: you must read this book. Hempel is one of those writers who makes you throw your hands in the air as you question everything you ever thought you knew about fiction. Each word she writes is precise, each punctuation mark carefully chosen. Embedded in these pages are life lessons without the in-your-face siren that says: this is a lesson, pay attention! And when she doesn’t offer a lesson, Hempel writes from a place of hindsight. Her stories make you crawl into another body’s world and live in it as if it were your own. Perhaps what makes her so special is her understanding of the human experience— of the emotions behind the choices people make. She excavates identifiable scraps of experience that leave you somewhere between laughter and tears — typically both.

Many of Hempel’s stories deal with the mundane, all-encompassing boredom that can result from loss, yearning, and failed relationships. It’s as though her goal is to find the place where trauma lives in the body, to pull it apart and dissect it all:

The worst of it is over now, and I can’t say that I am glad. Lose that sense of loss—you have gone and lost something else. But the body moves toward health. The mind, too, in steps. One step at a time. Ask a mother who has just lost a child, How many children do you have? “Four,” she will say, “—three,” and years later, “Three,” she will say, “—four.”

Amy Hempel claims to be a slow writer, one who agonizes over every sentence she writes; it took her over twenty years to amass the four hundred pages comprising this story collection. Her careful craft is evident in each exquisitely constructed sentence of wry humor and observation. Her superb wit and dazzling relatability will stay in your head long after you’ve put her work down. Read this book.

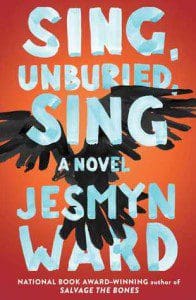

Isabel Erickson White, Intern: When asked to think of a great Southern writer, most likely one would respond with names from the past — William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Zora Neale Hurston, Tennessee Williams. We don’t often imagine the South as a place that still produces great literature. Jesmyn Ward’s voice, however, demands that we return our gaze to the South, and shows us that it can still produce incredible works. Ward’s work places her alongside the celebrated literature produced by the region’s previous writers; her latest novel has been described as a Southern odyssey and compared to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.

Isabel Erickson White, Intern: When asked to think of a great Southern writer, most likely one would respond with names from the past — William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Zora Neale Hurston, Tennessee Williams. We don’t often imagine the South as a place that still produces great literature. Jesmyn Ward’s voice, however, demands that we return our gaze to the South, and shows us that it can still produce incredible works. Ward’s work places her alongside the celebrated literature produced by the region’s previous writers; her latest novel has been described as a Southern odyssey and compared to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.

Her first work of nonfiction, Men We Reaped, was a soul-crushing memoir about the losses of five men in her life due to drug addiction, suicide, and accidents. Ward’s book took statistics about black male life expectancy and the ravages of Hurricane Katrina, and shaped them into a narrative about five caring, much loved men from her life — men whose lives had great meaning and whose deaths were keenly felt. The final loss Ward suffered was that of her younger brother, whose death remains a looming presence over her most recent work of fiction, Sing, Unburied, Sing. The novel is about three generations of a family—Mam, Pop, their daughter Leonie, and Leonie’s two children, Jojo and Kayla—living in southern Mississippi. Ward takes her reader on a road trip through Mississippi, starting at the southern end, where the air smells of the Gulf, and ending in the north at Parchman prison, a symbol of Southern racial violence and convict leasing. Ward travels from present day as Leonie, her children, and a drug dealing friend go to pick up the children’s father at the prison, to the past when Leonie’s brother died as Pop endured his days in prison. As in her memoir, Ward is capable of making characters on a page feel as real as the members of one’s own family. She mercilessly drags her reader into the story; the pain from the loss of Leonie’s brother, Given, is not something one merely reads or observes, but something felt viscerally, as if you’ve experienced the loss yourself. This novel is nothing short of a masterpiece.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Gillian Conoley announced her arrival on the literary scene with 1987’s evocative debut, Some Gangster Pain. To revisit this collection today is to be reminded of the pleasure of experiencing a vivid poetic milieu. Conoley’s critical lens is trained on the South, a region ravaged by both beauty and violence — that American dichotomy. Whether she’s rendering the Texas plains or New Orleans’ French Quarter, Conoley creates images that emerge from the page like phantoms: “the cicadas, thick in the air” and their drone like “a scratched record/spinning above her,” or the bulldozers churning up a graveyard depicted as “yellow tanks steamshovelled/for the underworld.”

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Gillian Conoley announced her arrival on the literary scene with 1987’s evocative debut, Some Gangster Pain. To revisit this collection today is to be reminded of the pleasure of experiencing a vivid poetic milieu. Conoley’s critical lens is trained on the South, a region ravaged by both beauty and violence — that American dichotomy. Whether she’s rendering the Texas plains or New Orleans’ French Quarter, Conoley creates images that emerge from the page like phantoms: “the cicadas, thick in the air” and their drone like “a scratched record/spinning above her,” or the bulldozers churning up a graveyard depicted as “yellow tanks steamshovelled/for the underworld.”

Although many of these poems were originally featured in outlets such as The American Poetry Review and Ploughshares, they form a remarkably cohesive tapestry gathered as they are here, arranged by Conoley into three separate Parts. As a writer in her early thirties, Conoley displays both youthful candor (“There is no peace in my mind anywhere”) and a battle-tested wisdom (“We can be kin/in an eternal house,/your hair falling to my shoulders/if my thoughts become too private”).

Conoley’s poems read as minimalist, rarely longer than a page each and with sparse lines, but her details prove as lucid and precise as photographs. Her words speak to a pastoral landscape haunted by loneliness, insomnia, and the lingering imprint of the mythic West. Images and sounds begin to accrue: a sorry Texas bar with Patsy Cline on the stereo, a horse wildly bucking at the rodeo, the light of the drive-in’s screen reflected off the hoods of cars.

Some Gangster Pain traffics in the ghosts of our collective memory, both channeling and challenging the origin stories we tell ourselves about our country (“The white man…lassoed the stars and rode amuck”). Throughout the book, we witness Conoley’s fascination with hands, and again and again we see those hands plunge into the soil, stirring up the resting place of those who came before and our own ultimate destination — when at last “There is nothing but sleep.”

Ingrid Vega, Intern: What began as a doctoral thesis at Columbia University was re-written to become an award-winning book by Dr. Nina Ansary. In Jewels of Allah: The Untold Story of the Women in Iran, Dr. Ansary aims to “lift the veil of misunderstanding” by chronicling the women’s movement unique to Iran and Islam, as well as attempting to answer the controversial question, “Can women in Iran be equal?”

Ingrid Vega, Intern: What began as a doctoral thesis at Columbia University was re-written to become an award-winning book by Dr. Nina Ansary. In Jewels of Allah: The Untold Story of the Women in Iran, Dr. Ansary aims to “lift the veil of misunderstanding” by chronicling the women’s movement unique to Iran and Islam, as well as attempting to answer the controversial question, “Can women in Iran be equal?”

She directly addresses popular misconceptions born out of the coups, wars, and revolts that have shaped modern Iran. While the Islamic Revolution of 1979 brought many negative effects to women of Iran, Dr. Ansary Argues that one should look deeper below the surface: “The quasi-westernized education that these girls received in single-sex institutions is one of the underlying reasons a women’s movement has developed in post-revolutionary Iran.”

Ansary illuminates the paradigm of feminism unique to Iran — “Islamic Feminism,” as coined by female expatriates. This paradigm seeks to “break the bonds of tradition through the reinterpretation of Koranic passages” and runs in parallel to nonreligious contemporaries. She also notes how journalism has been central to the dissemination of information that has helped strengthen the women’s movements in the post-revolutionary era. There were many great (yet short-lived) Iranian feminist journals from the post-modern, but the most influential and long-standing was Zanan (meaning Women) which ran from 1992-2008.

Zanan published brazen articles like “Sir, Have Your Ever Physically Assaulted Your Wife?” and “Man: Partner or Boss,” and republished excerpts of Western feminist classics such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Simone De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), which helped to rejuvenate and strengthen the women’s movement. It also furthered the Sharia-based discourse characterized by Islamic Feminism. Much to the public’s surprise, Zanan survived for 16 years and its founder was eventually cleared of all accusations, including “collusion and conspiracy with the West.”

Dr. Ansary is optimistic and claims that the Iranian women and youth “could be an instrumental force in effecting its dissolution,” and believes this movement will persist in Iran until “they are granted the divine compassion they deserve.” She ends the book with a compendium of outstanding women from Iran – such as Olympians, actresses, and politicians. She also shares several of her own personal philosophies, including “You will never find what lies deep within if you choose to remain in shallow waters,” a quote that perfectly aligns with the ethos of the entire work.

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: Books have a way of finding us when we’re ready for them, which is why we keep so many stolid stacks of them around our homes. They bide their time. Åsne Seierstad’s One of Us: The Story of Anders Breivik and the Massacre in Norway (translated by Sarah Death), published in the U.S. in 2015, chronologically relates the personal histories of a terrorist and his victims, following their separate paths to July 22, 2011, when their stories would disastrously meet, and on through Breivik’s trial.

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: Books have a way of finding us when we’re ready for them, which is why we keep so many stolid stacks of them around our homes. They bide their time. Åsne Seierstad’s One of Us: The Story of Anders Breivik and the Massacre in Norway (translated by Sarah Death), published in the U.S. in 2015, chronologically relates the personal histories of a terrorist and his victims, following their separate paths to July 22, 2011, when their stories would disastrously meet, and on through Breivik’s trial.

On that July day, Breivik would methodically murder 73 people, the vast majority of whom were teens on a Workers’ Youth League retreat on the island of Utøya. A harrowing if brisk read, Seierstad’s book is, unsurprisingly, difficult to get through. But given the current circumstances, the story—which is also the story of Europe’s far right, of the racism and xenophobia championed by Norway’s ironically named Progress Party, of poisonous misogyny and Internet delusion, and of a view of the left as the enemy of civilization—is, alas, more relatable now than before the 2016 election.

One pores through One of Us as if looking for clues to the future. There are certain details, which may or may not mean anything: their people believe themselves to be exceptional, too—citizens of the best country on Earth, in fact; their youth also champion equality and social responsibility, and are averse to profit at the expense of society. Also interesting: Norway’s colors are red, white, and blue. But also this: Norway’s society, as reported by Seierstad, is something of a marvel. Children are encouraged to assert their voices and play a part in meaningfully shaping their future. Education isn’t starved; decent housing and social services are prioritized. What do those details mean then, if anything? What an anxious way to read a text! Still, what lays ahead? The rising dawn or the plunge into midnight?