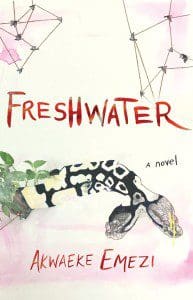

Akwaeke Emezi is a Tamil and Igbo writer from Nigeria who has received recognition for her short stories and creative nonfiction, as well as her work as an experimental video artist. With Freshwater (229 pages; Grove Press), she marks her first novel, an ambitious and original one at that. The book follows Ada, a young girl growing up in Nigeria, as she is both plagued and protected by a host of spirits that cohabitate her body and share her thoughts. Through beautiful and haunting prose, and through the different voices residing in Ada, we get a glimpse into her mind, a metaphysical space of “ọgbanje” (an Igbo term for a spirit that brings misfortune to a family by inhabiting the body of a child). Although Ada has been chosen by the god Ala to share her physical vessel with the ọgbanje, Emezi’s representation of her fractured mind proves surprisingly universal.

Akwaeke Emezi is a Tamil and Igbo writer from Nigeria who has received recognition for her short stories and creative nonfiction, as well as her work as an experimental video artist. With Freshwater (229 pages; Grove Press), she marks her first novel, an ambitious and original one at that. The book follows Ada, a young girl growing up in Nigeria, as she is both plagued and protected by a host of spirits that cohabitate her body and share her thoughts. Through beautiful and haunting prose, and through the different voices residing in Ada, we get a glimpse into her mind, a metaphysical space of “ọgbanje” (an Igbo term for a spirit that brings misfortune to a family by inhabiting the body of a child). Although Ada has been chosen by the god Ala to share her physical vessel with the ọgbanje, Emezi’s representation of her fractured mind proves surprisingly universal.

Freshwater begins with a narrator called “We,” a group of spirits who first exist in Ada’s mother’s body. “We” describe themselves as “the hatchlings, godlings, ọgbanje,” and act with indifference to the needs and interests of humans. The day they come into complete being is the day of Ada’s birth, “the day we died and were born.” Ada’s conception is explained by her father’s request for a daughter, which the god Ala answered. In doing so, Ada’s father opened a gate to the spirit world, summoning these entities into his family’s lives. When their little girl arrives, the happy parents name her Ada, meaning, “God answered.” “We” regards Ada from an observational perspective, but “We” and Ada often share the same desires, such as the need for blood, which they satisfy through Ada’s self-cutting.

Ada primarily shares her mind with “We” until she leaves Nigeria to attend university in Virginia. When Ada arrives, she is marked as prudish because of her disinterest in sex, telling her friends that she has made a vow of celibacy. But after her boyfriend sexually assaults her, a new ọgbanje appears—the licentious Asughara—whose purpose is to protect Ada by taking control of her whenever men are involved. Asughara adds an important depth to Emezi’s story, eliciting conflicting emotions. Ada and Asughara argue in the “marble room” of Ada’s mind and build a codependent relationship, leaving us to wonder if Asughara is protecting or harming Ada. Despite the uncertainty, one sighs with relief when Ada’s attempt to seek treatment from a therapist is thwarted because the therapist seems like an unwelcome third party who would create a wedge between Asughara and Ada. As “We” explains, the gods living in humans are inescapable; it is better to feed them than to ignore them.

Befitting a story about a fractured mind, the style of the novel is unconventional. Not only does Emezi write in multiple voices, but the story also progresses in a nonlinear fashion. Her writing compresses time and space—the past, future, and present moments in Ada’s life are ever-present, as are the places and people she visits. It begins with Ada’s birth, but once Ada reaches Virginia, the text moves back and forth in time, in ways that are often confusing. The organization of events is not without purpose, however. After the sexual assault, Asughara chronicles Ada’s adult life and often returns to the time before the assault and then far into the future. By doing this, Emezi reveals Ada and the ọgbanje in a way that resists an understanding of Ada as two separate selves: the Ada before the assault and Ada after. This pushes the young man who assaulted her out of the spotlight—we regard him as a negative influence in Ada’s life, but not as the key acting figure.

Ultimately, Emezi offers a perspective on mental illness that refuses categorization and diagnoses. Rather than characterizing Ada’s behaviors—her insatiable sexual appetite after being raped, her self-mutilation, alcoholism, and an eating disorder—as coping mechanisms or symptoms of mental illness, Emezi attributes them to conflicts between our spiritual and physical selves. She also refuses to portray the spirits that lead Ada to acts like self-harm as entirely malevolent. As she makes clear, Asughara and the other ọgbanje love Ada, and exist to protect her. (Often there’s the sense Ada should give herself up entirely to the ọgbanje, who, unlike Ada, cannot experience pain from the outside world.) With her brilliant novel, Emezi shows how the different aspects of our personality are often in conflict, and how that conflict can be inescapable.