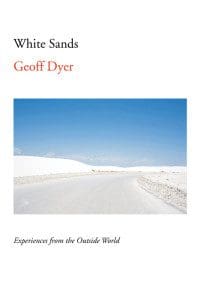

There are a few different types of ignorance at work in Geoff Dyer’s new book, White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World, a collection of essays that combine travel writing and art criticism. One kind is artificial ignorance as an interpretative tool. Often, when he is ignoring information, sloughing off context on which another critic might lean all his weight, Dyer (or the genre-bending author’s narrator whom I will call Dyer) is at his sharpest. In “Space in Time,” the author travels to Quemado, New Mexico, to see Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field, but he holds off telling us this information until the second half of the essay. In the meantime, he makes surprising observations about the experience of viewing the work, the most intriguing of which concern absence. The “abundance of poles and wind” creates “an implied absence of flags.” Another art pilgrim is walking around at twilight holding a champagne glass, which, “for most of that hour, had been empty.” As night falls, the viewers are “in the midst of what may once have been considered a variety of religious experience. Absence had given way to presence.” Even after he tells us what we are looking at, he continues constructing his analysis around a hypothetical lack of data, ignoring De Maria’s “obsessively minute inventory and visionary manifesto, ‘The Lighting Field: Some Facts, Notes, Data, Information, Statistics and Statements,’” in favor of a “subterfuge of inconceivable ignorance”: “So what if we visited the site years hence and had to try to figure out for ourselves what was happening here, what forces were at work with no art-historical context (minimalism, conceptualism, taking work out of the gallery into the expanded field, etc.)?” Not knowing exactly where we are can give us a much clearer idea of where we are.

There are a few different types of ignorance at work in Geoff Dyer’s new book, White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World, a collection of essays that combine travel writing and art criticism. One kind is artificial ignorance as an interpretative tool. Often, when he is ignoring information, sloughing off context on which another critic might lean all his weight, Dyer (or the genre-bending author’s narrator whom I will call Dyer) is at his sharpest. In “Space in Time,” the author travels to Quemado, New Mexico, to see Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field, but he holds off telling us this information until the second half of the essay. In the meantime, he makes surprising observations about the experience of viewing the work, the most intriguing of which concern absence. The “abundance of poles and wind” creates “an implied absence of flags.” Another art pilgrim is walking around at twilight holding a champagne glass, which, “for most of that hour, had been empty.” As night falls, the viewers are “in the midst of what may once have been considered a variety of religious experience. Absence had given way to presence.” Even after he tells us what we are looking at, he continues constructing his analysis around a hypothetical lack of data, ignoring De Maria’s “obsessively minute inventory and visionary manifesto, ‘The Lighting Field: Some Facts, Notes, Data, Information, Statistics and Statements,’” in favor of a “subterfuge of inconceivable ignorance”: “So what if we visited the site years hence and had to try to figure out for ourselves what was happening here, what forces were at work with no art-historical context (minimalism, conceptualism, taking work out of the gallery into the expanded field, etc.)?” Not knowing exactly where we are can give us a much clearer idea of where we are.

We see Dyer realize the value of this heuristic approach when he experiences an actual lack of information in the opening essay, “Where? What? Where?” Fittingly, this piece takes the loss of information as its starting point. Dyer is on his way to Tahiti where he is travelling to write about Gauguin in honor of the centenary of his death when he loses his copy of David Sweetman’s biography of the French artist, the first of many disappointments to come. Dyer even complains about the flawless ocean, which “seemed manicured, as if it were actually part of an aquatic golf course to which guests enjoyed exclusive access.” The trip’s pattern of letdowns reminds him of another, earlier disappointment. He goes to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts to see Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, which turns out to be unavailable for viewing. Inspired by Gauguin’s interrogatives and, more importantly, by their absence, Dyer pursues his own line of interrogation: “what is the difference between seeing something and not seeing it? More specifically, what is the difference between seeing Tahiti and not seeing it, between going to Tahiti and not going to it? The answer to that, an answer that is actually an answer to an entirely different question, is that it is possible to go to Tahiti without seeing it.”

After various other disappointments, each of which is accompanied by astute and sometimes hilarious observations, Dyer is pleasantly surprised. On the final stop of a tour of Tahiti’s recently excavated sacred sites, one on which the heat-rash-afflicted author only begrudgingly embarks, he encounters “the gravitational force” of Polynesia’s biggest tiki: “There is an unmistakable power here. Even the leaves are conscious of it, can feel it, are part of it.” This enormous tiki (“the god of staying put,” Dyer quips) represents the Tahiti one can miss when traveling to Tahiti. This Tahiti is Tahiti. While this account is well turned, like everything Dyer writes, it also marks the beginning of a grandiosity that becomes less tolerable each time it crops up. The next day, Dyer’s musing on the village football pitch gets a little out of control. He poses the same hypothetical he does in “Space in Time,” imagining that a thousand years into the future “after [the pitch] had been overgrown with jungle and then rediscovered by some intrepid archeologist and the engulfing vegetation hacked back, this place would have something of the aura of Iipona or, for that matter, of many other places of apparently abandoned meaning.” But how do you “rediscover” a field that has been disappeared by overgrowth? How can something be simultaneously meaningless and meaningful? In “5,” one of the numbered vignettes that separate the longer pieces, Dyer, a Los Angeles transplant, seems to have been infected by the city’s many New Age mystic types. His meditation is centered on a picture of two tourists photographing the spot on a Thai beach where two murdered British tourists’ bodies were found: “…even if that knowledge fades, this spot will still exude an uncomprehended—possibly unnoticed—meaning.” He completely loses me here.

Still, the many oblique and precise reflections in these essays make the few moments of awkwardness easy enough to forgive. In the final essay, “Beginning,” Dyer recounts the story of a minor stroke, which leads him to consider his mortality. The emphasis on the human-lifetime-scale experience of time is juxtaposed by the book’s previous forays into (literal) monumental time. “Life is so interesting I’d like to stick around forever, just to see what happens, how it all turns out.” He calls back to the aforementioned moments in which he imagines how it might all turn out. And whether or not these musings pay off, they always prove Dyer has a notable imagination.

However, in at least one instance, there are limits on his imagination. In “Where? What? Where?” Dyer unsurprisingly tries to “think [him]self into Gauguin’s shoes.” But while he makes about half a page of fat jokes about modern-day Tahitians (the area, he writes, has a “distinctive twist on Darwinism: the survival of the fattest”), it apparently never occurs to him to try to imagine himself into the shoes (or the bare feet) of one of Gauguin’s myriad native Tahitian subjects.

Ultimately, reading this book might be described as the author himself describes the experience of being deprived of seeing Gauguin’s painting in Boston: it is a “thwarted pilgrimage (which is not at all the same as a wasted journey).”