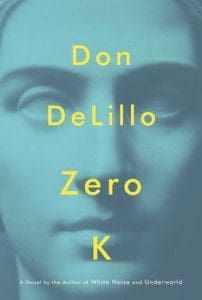

Don DeLillo’s seventeenth novel, Zero K (288 pages; Scribner), has all the trappings of a typical DeLillo novel. It opens with the protagonist Jeffrey Lockhart arriving at the Convergence, a techo-utopian compound erected in the midst of a central Asian desert. The compound is a staging ground for a series of experiments, led by the mysterious Stenmark Twins (or, at least that’s what Jeffrey calls them), into the possibilities of cryogenics. These experiments are meant to prepare their participants—including Jeffrey’s terminally ill stepmother, Artis, and estranged father, Ross Lockhart—for a future where death has ceased to exist and life may be everlasting. There’s little plot beyond this initial setup. Rather, DeLillo performs an elliptical investigation of the tensions between skepticism and belief, alienation and community, subjectivity and relationality.

Don DeLillo’s seventeenth novel, Zero K (288 pages; Scribner), has all the trappings of a typical DeLillo novel. It opens with the protagonist Jeffrey Lockhart arriving at the Convergence, a techo-utopian compound erected in the midst of a central Asian desert. The compound is a staging ground for a series of experiments, led by the mysterious Stenmark Twins (or, at least that’s what Jeffrey calls them), into the possibilities of cryogenics. These experiments are meant to prepare their participants—including Jeffrey’s terminally ill stepmother, Artis, and estranged father, Ross Lockhart—for a future where death has ceased to exist and life may be everlasting. There’s little plot beyond this initial setup. Rather, DeLillo performs an elliptical investigation of the tensions between skepticism and belief, alienation and community, subjectivity and relationality.

In this sense, Zero K sometimes seems like less of a novel and more of a philosophical treatise. Jeffrey aimlessly wanders the Convergence. Occasionally he encounters screens that descend at random to depict epic scenes of human suffering, as if to remind him of the mortality he might leave behind in the compound. A skeptic amid the Convergence’s utopian promise, he refuses to take the Stenmark Twins’ vision seriously. He’s convinced the entire project is a prank, a cosmic joke on gullible believers. To register his incredulity, he knocks on doors at random, certain no one is behind them, that the Convergence is a stage created for the purpose of an elaborate fiction. For the most part he’s confirmed in his suspicion—until someone answers and topples Jeffrey’s assumptions.

Elsewhere, Jeffrey trades barbs with a man who intones, “These rooms and halls, a stillness, a waiting. Aren’t all of us here waiting for something to happen? Something elsewhere that will further define our purpose here. And something far more intimate.” He’s speaking about the Convergence, but his language could allude as easily to the nature of religious belief in general, the way it grants solace through the promise of wholeness and intimacy. Jeffrey’s retort to this sense of longing is typically cynical: “I told him that what was gathering could well be a kind of psychological pandemic … Something people want from time to time, purely atmospheric.”

Thus, we find DeLillo returning to themes of postmodernity that have consumed his entire writing career. In loose fashion, the novel circles around the ways in which mortality shapes human life and in technology’s potential to upend death and reshape what it means to be human. Along the way, DeLillo touches upon language’s status as a constructed medium that elides the chasm separating individual subjects; the need for fictions that might bestow narratives upon an otherwise meaningless world, and the importance of naming. In this sense, Zero K reads as a retread of ideas DeLillo might have explored more fruitfully in past novels. Artis’ and Ross’ imminent deaths recall Jack Gladney’s race against mortality in White Noise, and Ross’ own taking of a new surname reminds one of Charles Maitland’s ruminations on nations and names in DeLillo’s 1982 novel, The Names.

Along with a return to well-worn ideas, we get a return to DeLillo’s characteristically stark prose. The characters speak in a clipped, hyper-erudite fashion that defies normal speech patterns, and environments are rendered in austere language. This isn’t always a good thing. At times—especially in the sleek, aggressively minimalist first half—the novel seems to parody the prophetic tone for which DeLillo has become famous. In one scene, the Stenmark Twins present an interminable series of questions whose pretension is reminiscent of a late night college vamp session: “Once we master life extension and approach the possibility of becoming ever renewable, what happens to our energies, our aspirations … Isn’t death a blessing? Doesn’t it define the value of our lives, minute to minute, year to year?” Though the prose sometimes possesses a deadpan quality that makes one wonder whether DeLillo is pulling his own prank to go along with that of the Stenmark Twins’, the accumulated effect of such moments suggests a thin pseudo-intellectualism that parody can’t rescue.

This is an unusual novel, though, one whose face changes every sixty pages; DeLillo doesn’t get stuck in any one mode for too long. The novel’s highlight is the second half, which takes place an unspecified number of years after Ross and Jeffrey’s reunion at the Convergence. Freed from the Convergence, the novel seems warmer and more fleshed out. It finally deals with characters more than ideas and does so in striking, sometimes lyrical language. Specifically, it becomes concerned with Jeffrey’s lived experience of technologically mediated alienation, and the ways he overcomes that alienation.

Most of this comes through Jeffrey’s reflections on life with his girlfriend in New York City. If the Convergence offered a false vision of communal intimacy, “purely atmospheric” promise of wholeness, Jeffrey locates the real thing in his relationship to her: “If I’d never known Emma, what would I see when I walk streets going nowhere special, to the post office or the bank. I’d see what is there, wouldn’t I, or what I was able to assemble from what is there. But it’s different now. I see streets and people with Emma in the streets and among the people. She’s not an apparition but only a feeling, a sensation … This is my perception but she is present within it or spread throughout it. I sense her, feel her, I know that she occupies something within me that allows these moments to happen, off an on, streets and people.”

This pivot, from what Jeffrey is able to assemble with his own mind to what he can build in and through inter-subjectivity with another person, is at the heart of Zero K’s inquiry. It’s ultimately concerned with how what we perceive—and who we are—gets constituted in and through our relations with others. By the novel’s end, it turns out that the techno-utopian setting was indeed a feint all along.