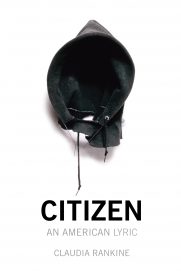

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (160 pages; Graywolf) explores the subtleties of racism and prejudice that seem all too prevalent in an oft-claimed post-racial United States. Rankine delves into the macrosociology of racism by examining prejudice in sports, economics, and pop-culture, and melds her pinpoint analysis with individual experiences of alienation and otherness at restaurant tables, front porches, and boardrooms. Citizen observes racism from a myriad of angles, employing a clever and effective combination of second person perspective with the speaker’s internal monologue, and fusing various lyric and reportorial forms with classic painting and contemporary multimedia art.

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (160 pages; Graywolf) explores the subtleties of racism and prejudice that seem all too prevalent in an oft-claimed post-racial United States. Rankine delves into the macrosociology of racism by examining prejudice in sports, economics, and pop-culture, and melds her pinpoint analysis with individual experiences of alienation and otherness at restaurant tables, front porches, and boardrooms. Citizen observes racism from a myriad of angles, employing a clever and effective combination of second person perspective with the speaker’s internal monologue, and fusing various lyric and reportorial forms with classic painting and contemporary multimedia art.

In constructing a racial identity, the speaker of Citizen cites what a friend had once told her— that there exists a “Historical Self” and a “Self-Self” that are in disagreement with race. When the historical knowledge of racism and the expectations of its ubiquity are placed beside the global-citizen, the individual, it prompts a sort of cognitive dissonance. This “is how you are a citizen: Come on. Let it go. Move on,” the speaker says, feeling alone in her otherness. Moving through the book-length lyric poem, the reader comes to empathize with the flinching nature of the judged—“Every day your mouth opens and receives the kiss the world offers, which seals you shut…the go-along-to-get-along tongue pushing your tongue aside.” Rankine explores racism and ignorant racial prejudice as a sort of unspoken, public exile, and the blind search for a solution, which only at times, sadly, is to become a citizen.

In the first section of the book, composed of personal and situational vignettes, the speaker meets her manager for the first time. He says, “I didn’t know you were black!/ I didn’t mean to say that, he then says./ Aloud, you say./ What? he asks./ You didn’t mean to say that aloud.” This exchange perhaps enters the heart of prejudice in Citizen, by displaying if not blatant racism, then an unnecessary acknowledgement of the “Historical Self” that runs under the surface of every conversation, every situation. The acknowledgement “arrive[s] with the full force of your American positioning” and destabilizes our normal relationships.

A collage of forms run throughout Citizen. There’s Rankine’s lyric poetry, which flows like spoken word, using clear and concise language in the style of reportage, She even appropriates, excises, and reorganizes transcripts from CNN to disturbing and powerful effect:

“He gave me the flashlight, she said, I didn’t want to turn it on. It was all black. I didn’t want to shine a light on that.

“We never reached out to anyone to tell our story, because there’s no ending to our story, he said. Being honest with you, in my opinion, they forgot about us.”

In this combination of CNN transcripts, Rankine evokes the first images of flooding and helplessness associated with Hurricane Katrina. In the aftermath of this destruction, a voice speaks out, but only to say that to speak out, to display blackness, is too much to bear. The speaker feels muted—the following voice feels that the world has forgotten this plea, these people. They are hidden in plain sight.

Rankine also presents a series of related pieces initially published as video essays (in collaboration with John Lucas), which work as refrains for the dead. Their titles—the various dates of particular incidents such as the deaths of Trayvon Martin, James Craig Anderson, Mark Duggan, the intense/unjustifiably strong persecution of the Jena Six, a stop-and-frisk, and Zinedine Zidane’s World Cup ejection—enhance the work’s gravity, placing it strongly in the present and known.

Citizen constantly works in concert with itself, bouncing back and forth like a tennis ball across a net. In a drugstore, a man cuts in front of the speaker. He says, “Oh my god, I didn’t see you./ You must be in a hurry, you offer./ No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.” This line troubles the reader, as the man’s initial alarm, which contains a shard of fear, becomes overtly insistent, apologetic over what should be a banal and accidental infraction. These moments of heightened attention, of obfuscation of meaning, illuminate everyday prejudice, while Rankine’s use of the second person activates our curiosity at the man’s action, and, ultimately, empathy and realization when juxtaposed with the other pieces in Citizen.

Along with her collaborations with John Lucas, Rankine showcases Glen Ligon’s art in Citizen. Ligon borrows the words of Zora Neale Hurston, “I do not always feel colored,” and “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” These words are displayed in bold-faced, black text, repeating over and over again until they run together and become splattered with ink at the bottom of the page. Rankine is understandably occupied with visibility—she makes references to Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man), and philosopher Judith Butler’s idea that “Out emotional openness…is carried by our addressability.” Rankine then adds, “For so long you thought the ambition of racist language was to denigrate and erase you as a person…you begin to understand yourself as rendered hypervisible in the face of such language acts. Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present…your looking up, your talking back as insane as it is, saying please.” So what does this mean when racism in America has largely transformed into the unspoken, the passing look, a certain type of careful attention, or perhaps simple ignorance? When racism is a referee, calling five bad calls on Serena Williams, who says, “’no, no, no,’ as if by negating the moment she could propel us back into a legible world”? (Rankine, it should be noted, not only links the various elements of Citizen thematically, but technically as well. The repetition of “no, no, no” sets off a comparison of two people in opposite situations: Williams, who cannot believe the ludicrous and unwarranted calls on her game, and a man who is being oversensitive as a result, perhaps of his pointed attempt to avoid race.)

Citizen invites research. It invites outrage, sadness, empathy, and knowledge. It seeks to educate by analyzing negative culture and attitudes that are put forth as gospel, and it does so intricately and inventively. Rankine implores us to be more than citizens. We should speak out to, if not end the absurdity of racial prejudice, then at the very least to be made aware of it.

One thought on “Racism Transformed into a Given: ‘Citizen: An American Lyric’ by Claudia Rankine”