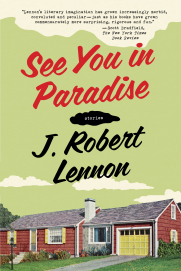

Compiled from fifteen years of work, the stories in J. Robert Lennon’s new book, See You in Paradise (Graywolf Press; 256 pages) dwell on quotidian fears and dissatisfaction and on the strange nature of contemporary American life in modern suburbia, which can be found here in run-down mountain communities, lakeside cabins, and college towns. In this collection, ordinary people find themselves straddling mundane reality and its bizarre or magical undercurrents. Drawing elements from science fiction, horror, and the surreal, several of Lennon’s stories manifest these undercurrents in more literal ways than others. But the disaffection of their characters, the often absurdist butterfly effect triggered by their plots’ movements, and the feeling that anything can and will happen, are what unite all these pieces.

Compiled from fifteen years of work, the stories in J. Robert Lennon’s new book, See You in Paradise (Graywolf Press; 256 pages) dwell on quotidian fears and dissatisfaction and on the strange nature of contemporary American life in modern suburbia, which can be found here in run-down mountain communities, lakeside cabins, and college towns. In this collection, ordinary people find themselves straddling mundane reality and its bizarre or magical undercurrents. Drawing elements from science fiction, horror, and the surreal, several of Lennon’s stories manifest these undercurrents in more literal ways than others. But the disaffection of their characters, the often absurdist butterfly effect triggered by their plots’ movements, and the feeling that anything can and will happen, are what unite all these pieces.

The opening story, “Portal,” sets the tone with its unceremonious appropriation of magic into an ordinary setting. A family discovers a portal in their backyard that sends them to alternate universes, but the device soon becomes overused and lackluster, falling into disrepair like an abandoned piece of furniture. When the portal falls into a “senile,” nonsensical state, it sends them to dimensions that reveal each of their hidden—and unnerving—desires, and they soon lose interest altogether in their family trips. As each family member begins to escape into his own psychic landscape (without help from the portal), the story offers a sincere depiction of the cold dissatisfaction and solitude felt in a deteriorating family.

The strangeness found in ordinary familial and romantic relationships and friendships, and the surprising ways the kinks in their connecting bonds can be cast to light are further explored in Lennon’s stories. “Total Humiliation in 1987” depicts the tensions that arise after a family discovers a different family’s time capsule in their lake house—a time capsule that reveals their broken relationships and unhappiness. In “Zombie Dan,” a group of friends are given the chore of rehabilitating a deceased and subsequently revived childhood friend, one whom they lost interest in even before his death. And in “Hibachi,” a quiet, modest couple adjust to each other after the husband becomes wheelchair-bound, and whose marital life gets transformed with the help of the ostentatious grill of the title.

Lennon’s stories display a fascination with the psychology of individuals when faced with the unexpected. Indeed, Lennon is a master at creating characters who can be both neurotic and apathetic, characters with poignant flaws that make them act and think in unpredictable ways; he crafts situations in which a character’s response to the strange and the mundane can swing from one emotion to its polar opposite.

In “The Wraith,” Lurene, a chronically unhappy woman (Lurene is clear to distinguish her state from depression; the former is a condition, while unhappiness is more of a way of life), reaches her breaking point. Rather than causing her death, an attempted suicide instead frees a grotesque ghost from her body. Carl, her husband, at first endures the heavy presence of both Lurenes in his home—the specter-esque version and the now-horribly-happy one—but soon learns to simply live with it.

Showing people adjust to incredible circumstances is part of what gives these stories their power. We seem to have an almost supernatural ability to cope with the mind-bending and heart-wrenching. And the way we can quickly adjust to the uncanny is often frightening: in “The Wraith,” the husband discovers that his fear of the corpse-like monster has transformed into sexual longing. Throughout the collection, the line between what is acceptable and what is not disappears.

While the fantastical stories in See You in Paradise do stand out, and not so much because of their unconventional allure as for their witty, honest portrayals of complex people many of the stories sans magic are equally strong. In “Weber’s Head,” a humorous story with the makings of a horror tale, a terrible, too-talkative, too-involved roommate moves in, and despite the narrator’s disdain for him, John Weber’s antics give the narrator a new sense of self-awareness.

“For a moment, I was suspended between […] contradictory channels of annoyance, and in that weightlessness felt the presence of a terrifying possibility: that John Weber’s obliviousness and intensity were, in some twisted way, actually profound. That there was substance to him, a substance that I would forever lack.”

Like the narrator in “Weber’s Head,” Lennon’s characters are often bound within their limited perspectives at the start of each story. They are too complacent to notice their own complacency, too short sighted to see their flaws from a different vantage. Contradiction and cognitive dissonance is what transforms most of them. Though we are presented with very true and thought-provoking ideas about the complexity of humans, these revelations become repetitive as the collection unfolds: the plot of each story is unique, but the hinge on which they sway is almost always the same.

However, this story collection is one that truly feels like a collection—a solid thematic through-line and connective parts that speak enough of the same language for all the stories to coexist harmoniously. Yet there’s enough variation in each story to give them life, to make them seem fresh, though some fresher than others. Lennon is a writer with consistent habits, and by the end of the collection we believe we understand what those are.

Lennon’s work is profound and at the cutting edge of contemporary fiction. He is apt to describe a simple intake of breath, or a man’s face, with fierce specificity, to invoke humor on the gruesome, or to find the harrowing in what is peaceful. He pushes the limits of possibility in his stories; in his world, nothing is too far out of reach. See You in Paradise stirs up what ought not to be stirred, and we are left forever grateful for that.