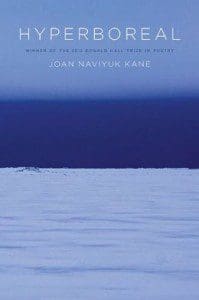

“I could make passage / A thousand obscure, / Contradictory ways,” claims Joan Naviyuk Kane in “Mother Tongues,” a poem from the collection, Hyperboreal (University of Pittsburgh Press, 65 pages), winner of AWP’s Donald Hall Prize in Poetry. In five precise, prosodic quatrains, the poem navigates vast and difficult territory, memorializing both the poet’s mother and her mother’s native tongue, the King Island dialect of Inupiaq. An Inupiaq/Inuit, and among the last living speakers of the King Island dialect, Kane contends with biological, cultural, and political threats to her ancestral community, including climate change, language death, and the diaspora prompted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ forcible relocation of King Island residents in the mid-twentieth century. Yet as a mother and a daughter, an educator and an artist, Kane brings to these subjects a singular, sonorous voice and a lyric sensibility as alternatingly austere and lush as the land of her ancestral home.

“I could make passage / A thousand obscure, / Contradictory ways,” claims Joan Naviyuk Kane in “Mother Tongues,” a poem from the collection, Hyperboreal (University of Pittsburgh Press, 65 pages), winner of AWP’s Donald Hall Prize in Poetry. In five precise, prosodic quatrains, the poem navigates vast and difficult territory, memorializing both the poet’s mother and her mother’s native tongue, the King Island dialect of Inupiaq. An Inupiaq/Inuit, and among the last living speakers of the King Island dialect, Kane contends with biological, cultural, and political threats to her ancestral community, including climate change, language death, and the diaspora prompted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ forcible relocation of King Island residents in the mid-twentieth century. Yet as a mother and a daughter, an educator and an artist, Kane brings to these subjects a singular, sonorous voice and a lyric sensibility as alternatingly austere and lush as the land of her ancestral home.

“Mother Tongues,” like many of these poems, is studded with Inuit words: “Mother, / Aakaa; Woman, / Aġnaq.” Occasionally, these terms remain un-translated, as in “Time and Time Again” and “Nunaqtigiit.” While these entries may not offer most readers much in the way of semantics, Kane’s periodic refusal to translate testifies to the irreducibility of these messages, and to the impossibility of paraphrase from a language suffused with the knowledge of its own endangerment. As Spivak would have it, one cannot make widely legible an experience whose illegibility to dominant culture is among its fundamental experiential features. Or, in Kane’s own words, “The sky of my mind against which self- / betrayal in its sudden burn / fails to describe the world.”

Additionally, two poems appear both in English and in Inupiaq: “Innate,” or “Ilu,” and “Procession,” or “Maliktuk,” which contribute much to Hyperboreal’s sonic textures. Full of nasal, velar, and uvular consonants (n’s and g’s and q’s, for instance), the Inupiaq words are long and resonant, comprising no fewer than two syllables and often as many as six. Likewise, Kane’s English diction embraces the polysyllabic and recondite; winds are “katabatic;” branches are “dentritic;” and, in a particularly lyric stanza, wakefulness is “sublux, sural and dull.” Her efforts to render the world with clarity and rigor take her often into more technical lexica.

Just as often, though, Kane’s poems are terse, declarative, and deceivingly simple. “In Long Light,” from Section III of the book, reads as follows:

The sooty night a backdrop

for a slip of rowan trees,

swans in migration.

Beneath the ice

in its interminable thaw

streams improbable

but assuredly there—

these things contained,

not trapped by the world.

What I mean to say is,

I am not sure I will ever

become the person

I had hoped, or forgive

myself the inaccuracy

of estimation. It is

one thing to blame

the glare of the sun

and another to be held

(but not bound) through the

long fermata of dusk

and its promised repetition.

As in most of these poems, descriptions of the natural world blend with experiential anecdotes, so that a description of thawing ice (one of several in the book) segues into the confession, “What I mean to say is, / I am not sure I will ever / become the person / I had hoped.” Not only does Kane conflate the personal with the cultural in these poems, often making use of a first-person plural pronoun to speak for her ethnic community (“In a warm room, we were altered, alter / together: beyond this, comprehended for a plural”), she also blurs the boundaries between the cultural and environmental, the community and the land that sustains it. Some of Kane’s most arresting imagery anthropomorphizes elements of the landscape: rivers are “glossal;” the wind “revise[s]” a scene; and “night’s lopped moon / Couldn’t put into words / The ink around it.” Conversely, Kane’s human characters sometimes resemble their environments; in one poem, a girl’s heart is “a small stone,” while in another, it “put[s] forth blossoms.”

The complex transaction between ecological and emotional dictions is the essence of Hyperboreal. This interplay reminds us that, while global warming and globalization may represent distinct threats to arctic biomes and their indigenous human cultures, respectively, both phenomena share the same social and economic origins. To communities such as Kane’s, then, cultural extinction and biological endangerment are inextricable, and the interior landscape is mirrored by the exterior. “A glacier’s heart of milk loosed from a thousand // Summer days in extravagant succession, / From the back of my tongue, dexterous and sinister,” Kane writes in the opening poem. If poetry is the performance of experiential associations, Hyperboreal’s diffusion of personal, communal, and environmental subjectivities is a sophisticated, spellbinding poetic feat.

Likewise, as in “Mother Tongues,” Kane often confounds the roles of mother and daughter. (“I am a human being. // Daughter mother / Asunder,” she writes in the penultimate poem.) Additionally, the fact that Kane’s own children are boys seems to foreshadow an end to the cycle of matrilineal relationships in her family. To her mother, she writes, “You foresee the last time / We will be able to talk / Together—I, daughterless, / And you, who knew.” Yet, whether mothers or not, Kane’s characters are usually women; whether daughterless or not, all are resigned to their own obsolescence: “Here, every trace of us ends.” If Hyperboreal is, in part, an elegy to a dying culture, its author’s exquisitely lithic imagery and arresting, angular syntax may at least renew our faith in the power of language. Kane articulates an enduring vision of the world, both abstract and scrupulously grounded, collective and stunningly intimate. “There is no final story, / no assertion, no deception. / I may never know who I am,” Kane writes in “On Either Side.” Yet in the final stanza, noting a plant growing from fallow ground, she writes, “The shoot shifts ever toward the light.”