In his introduction to Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s Severina (Yale University Press, 112 pages), poet and translator Chris Andrews writes that for readers expecting the “baroque exuberance” of fellow Guatemalan writer Miguel Angel Asturias, Rey Rosa’s fiction will come as a surprise. Not only does Rey Rosa eschew the colorful language of his predecessor for more restrained and economical prose, he allows dreams, fantasies, and hallucinations to regularly puncture his character’s worlds. In this respect, Andrews observes, the writer who Rey Rosa remains the most in debt to is Jorge Luis Borges.

In his introduction to Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s Severina (Yale University Press, 112 pages), poet and translator Chris Andrews writes that for readers expecting the “baroque exuberance” of fellow Guatemalan writer Miguel Angel Asturias, Rey Rosa’s fiction will come as a surprise. Not only does Rey Rosa eschew the colorful language of his predecessor for more restrained and economical prose, he allows dreams, fantasies, and hallucinations to regularly puncture his character’s worlds. In this respect, Andrews observes, the writer who Rey Rosa remains the most in debt to is Jorge Luis Borges.

Reading Severina—only the fifth of Rey Rosa’s many works to be translated into English thus far (a task begun by Paul Bowles)—one cannot help but also draw comparisons to more contemporary Latin American authors, such as Roberto Bolaño, Horacio Castellanos Moya, and César Aira. Like them, Rey Rosa enjoys using the forms of genre fiction (particularly mysteries) to mask stories whose real subjects aren’t their tantalizing series of events, but the subtler, more inscrutable themes hidden within.

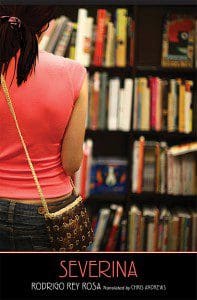

Severina follows the narration of a lovelorn owner of an eclectic bookstore, who becomes obsessed with a beautiful woman who comes to his store to steal books. He looks forward to her visits, and, for a while, tacitly indulges her habit, but eventually confronts her in the act. When he chooses to let her go, a flirtation opens up between them. He soon finds himself drawn into her strange orbit, and then into delirious love.

Her name is Ana Severina Bruguera Blanco, but he is sure of little else. She speaks with an unidentifiable accent—it could be Argentinian, or perhaps Uruguayan, he thinks—although she is listed as Honduran at the hotel where she stays. She is traveling with an older man, Otto Blanco, who a fellow bookseller (and fellow victim of her thefts) claims is her husband. But Otto could also be her father, or grandfather, or just some shady character in hiding with her. And then there is the question of why she steals in the first place—is it out of some sort of compulsion, like a sickness, or does she have another hidden reason? If so, what could it be?

“I kept going over the books she had taken from me and trying to imagine the complete list of every title she had ever stolen,” the narrator says. “It was as if I thought this would solve the mystery of a life that seemed bizarre and fantastic to me.” Rey Rosa builds the drama—the mystery—of their story through a steady escalation of tension and suspense. Peppered throughout, like discrete pauses, are the small lists the narrator makes of each stolen book. The effect is two-fold. First, it tantalizes the reader by supplying a set of what appears to be inscrutable clues as to Ana Severina’s nature and her motive to steal. More importantly, by refusing interpretation, the lists help to quietly move the narrative beyond the book’s surface plot and refocus it on the story’s real, underlying theme: literature.

The books, not the characters, are the point. In a passionate speech, Otto Blanco tells the narrator: “There are wars between different kinds or genres of books. And, as in real wars, the best don’t always win. We use these ebbs and flows the way a sailor uses ocean currents. We exploit them as best we can, beyond literary good and evil, so to speak. We, that is, [Ana] and I, are still navigating the tides and currents of books.” The narrator, perhaps blinded by his love for Ana, does not fully accept the significance of Otto’s words until, in the midst of a tense moment toward the end, he and Ana stop to read Reminders of Bouselham backward, sentence by sentence, since “that’s how it was written.” Afterward, he realizes that she has become a pure object of pleasure for him, like books. “You’re more interested in books than me, aren’t you?” he asks her then regrets it immediately.

In what could be seen as a subtle hint for the reader, instructing him how to proceed, the narrator remarks at the beginning that “Those were eventful days, or rather I heard that they’d been eventful (there was a rash of lynchings in the inland villages and a coup in a neighboring country, cocaine became the world’s number one illicit substance, stagnant water was discovered on Mars, and Pluto definitely lost its status as a planet), my life having shrunk once more to the ambit of books.” It is this “ambit of books” to which Severina eventually returns: a single text, intimately connected to none other than Borges himself, provides the novel with its end. It’s a fitting conclusion, not just because of Rey Rosa’s affinity for Borges’ work, but because like so many of Borges’ best stories, Severina is a nuanced but passionate homage to the act of reading, to a life lived, as the narrator finally puts it, “exclusively for and by books.”