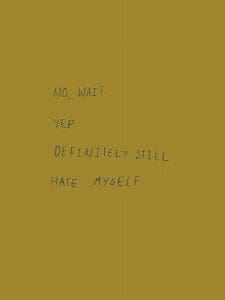

“I am a genius of sadness,” reads a line from Robert Fitterman’s book-length poem, No, Wait. Yep. Definitely Still Hate Myself. (Ugly Duckling Presse, 80 pages). “I am a prism / through which sadness could be / Divided into its infinite spectrums.”

“I am a genius of sadness,” reads a line from Robert Fitterman’s book-length poem, No, Wait. Yep. Definitely Still Hate Myself. (Ugly Duckling Presse, 80 pages). “I am a prism / through which sadness could be / Divided into its infinite spectrums.”

It’s as good a description as any of the book’s central premise: the appropriation of public articulations of loneliness and angst from blog posts, song lyrics, and ads, and the collaging of these excerpts, without context, in a relentless, eighty-page masterwork of Weltschmerz. Invariably first-person and homogenously histrionic, quotations give rise to an emergent “I” that is at once collective and personal. Mediated via Fitterman’s own curatorial bias, the speaker is simultaneously an individual and a univocal multitude, posting his pathos for all to see but incapable of finding succor in the near verbatim posts of others. Yet by applying to the passages an idiosyncratic, masculine affect, Fitterman makes the whole pastiche read like the work of one sad narcissist.

The book’s form borrows from James Schuyler’s “The Morning of the Poem,” a sixty-page epistolary poem that resembles a chapter of Ulysses: self-absorbed, associative, and lyrically beautiful, with a deictic duration far shorter than the time it takes to actually read. Like those of “The Morning of the Poem,” Fitterman’s lines increase gradually in length, with every other line indented, so that by the end, the poem has morphed into a monolithic paragraph without my even noticing. I am reminded of other authors in addition to Schuyler; Harold Jaffe’s found-text collection Anti-Twitter comes to mind, as does Ariana Reines’ Cœur de Lion, another book whose disarming candor makes me put it down intermittently to catch my breath and whisper “TMI.”

Because No, Wait… is, perhaps foremost, difficult to read. The poem enacts a vortical, cumulative sense of crisis that neither advances nor recedes but originates and sustains in the depressive subjectivity. Anyone who has ever been depressed knows that the inability of the mind to break with its own ruminative patterns is among the most frustrating, most depressing, stimuli of all. When taken together, the poem’s innumerable grievances perform a recursive spiral of distress and self-pity. While the complaints grow in number, they fail to be developed or problematized, to change in content or complexity. They go from saddening to infuriating, from cries for help to articulations of complacence and back again. In short, Fitterman’s clichés about sadness are partially recuperated via the same radical overuse that originally stripped them of their substance. In their accumulation, they become again oppressive, exigent.

As the poem achieves so much of its poignancy through the accrual of miseries, it is difficult to excerpt (and paraphrase is even more impossible). Still, I’ve reproduced the beginning of the book for reference:

I’ll just start: no matter what I do I never

seem to be satisfied,

The world spins around me and I feel like

I’m looking in from outside.

I go get a donut, I sit in my favorite part

of the park, but that’s not

The point: the point is that I feel socially

awkward and seem to have

Trouble making friends, which makes me very

sad and lonely indeed.

I am way too sensitive and always feel like

no one likes me.

I don’t know what to do—I’m just super tired

of feeling this way.

I used to really like people—I wasn’t always

imagining the Coney Island

Roller-coaster ride as, you know, a metaphor

for my life!

I am happy in the morning, yet at night

I’m mad, angry, sad, lonely,

And depressed, and above all, I’m starting to feel

like nobody cares about me:

I feel like everyone is selfish and mean.

Etcetera. The tone established here—simultaneously self-deprecating and -aggrandizing, conversational and a little clinical—sustains through the entirety of the book. While Fitterman’s humor is too self-aware to believably belong to the speaker, his bathetic interjections are nearly always funny, welcome diversions from the poem’s litany of platitudes. (My favorite is the insertion of misremembered Linkin Park lyrics—“I tried so hard, / I got so far, but in the end / it didn’t even matter”—between soliloquies on emptiness.) The only tonally distinct section is the book’s final stanza, which, by way of effecting climax, lapses into the schmaltziest imaginable monologue, like a video game avatar going up in bad CGI flames:

How I feel so dead here, sad and cold, as I hear crypt sounds of moan,

only thoughts of sorrow bring me down to the pits of

Bottomless black. In this endless extreme tomb of weeping sadness,

I am embraced by the cosmic force of night: pain dooming,

Death coming, shadows of misery are cast’d on the full moon, light

and stars of hellfire shine like a blinding bolt of lightning.

Dying alone in the woodlands, isolated in my empire of solitary death.

Total sadness, total darkness, total coldness, total pain.

Google tells me this stanza borrows heavily from lyrics by Colombian black metal band Inquisition. And how else to cap a poem about despair and triteness than with heavy metal lyrics, fraught with archaisms and apocalyptic diction, stock images of death and megalomaniacal hyperbole? To append a climax to a work whose primary rhetorical strategy is anticlimax, Fitterman must shift registers altogether. The ending is fitting: a gesture toward catastrophe in language too maudlin to signify real catastrophe.

Overall, No, Wait... does a really good job of drawing attention to the ways public media colonizes inner spaces. Fitterman dramatizes the process by which the vapidities and truisms of mainstream discourse determine the language through which we articulate our experience, and thus predetermine the experience itself. Further, he suggests that these vapidities and truisms are only vapid and truistic because their public applicability (and epigrammatic appeal) has changed them from subjective to universal statements via collective overuse. While the ubiquity of phrases like “love hurts” and “no one cares” might desensitize us to their relevance, it is their profound transpersonal value that leads to their ubiquity. Likewise, Fitterman reminds us that the media culture that foists itself so harmfully on our most private spheres is constituted exclusively by individuals like us—that, in short, the collective is always reducible to the individual. We are both the private victims and the public perpetrators of our suffering.

By its nature, the project is exploitative. Not so unlike Reznikoff versifying the testimonies of survivors in Holocaust, Fitterman uses the writings of suicide ideators and attempters to make a point about collective subjectivity. The knowledge of this appropriation makes my reading even more uneasy, more complicated. That their testimonies are exploited in service of a literary project makes me start to feel real sympathy for the speakers. They begin to seem actually oppressed. And maybe that’s the point; while trying to place Fitterman’s project in an ethical or epistemological framework, I’m frequently caught off-guard by my own emotionality and cathartic urges. The most generic, familiar declaratives—“I hate the person I am;” “I’m too afraid;” “I don’t fit in”—are often the points at which I start to over-identify, the points at which I have to put the book down and distract myself. That’s the thing about a poem that systematically disorders the boundaries between the collective and the personal: it starts to feel like it might be about me. It starts to feel, for lack of better language, lonely. It starts to feel sad.