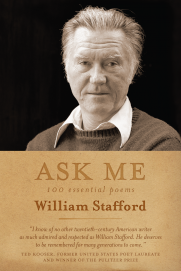

“Ask me whether / what I’ve done is my life,” writes William Stafford in the title poem of the recently released Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems (Graywolf Press; 128 pages). Published a century after his birth and twenty-one years after his death, the new collection includes 100 of Stafford’s “essential poems,” anthologized and introduced by his son, Kim. These poems repeatedly pose questions of individual and collective identity, challenging those false equivalences between our behaviors and our selves, and positing alternative relationships between the personal and political, the poetic and the vernacular. Ask Me suggests that Stafford’s life is larger than the sum of its actions—larger enough that it keeps speaking, years after it is over.

“Ask me whether / what I’ve done is my life,” writes William Stafford in the title poem of the recently released Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems (Graywolf Press; 128 pages). Published a century after his birth and twenty-one years after his death, the new collection includes 100 of Stafford’s “essential poems,” anthologized and introduced by his son, Kim. These poems repeatedly pose questions of individual and collective identity, challenging those false equivalences between our behaviors and our selves, and positing alternative relationships between the personal and political, the poetic and the vernacular. Ask Me suggests that Stafford’s life is larger than the sum of its actions—larger enough that it keeps speaking, years after it is over.

That Stafford is among the most important American poets of the twentieth century is beyond question. Awarded the 1963 National Book Award and appointed Poet Laureate (then Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress) in 1970, he composed around 20,000 poems, of which 4,000 were published in his more than 50 books. Motivated by passion and discipline—by the conception of poetry as both expressive mode and contemplative practice—Stafford’s poems are consistently concerned with moments of what Emerson calls “delicious awakenings of the higher powers,” when attention is so finely attuned to experience that the perceiving ego is radically diminished. In Stafford’s words, these are moments when “everything / [recognizes] itself and [passes] into meaning.” Of his early morning writing practice, he writes, “Let the bucket of memory down into the well, / bring it up. Cool, cool minutes. No one / stirring, no plans. Just being there. // This is what the whole thing is about.” Yet as much as poetry is a site for quiet revelation, it is also a political and pacifistic enterprise for Stafford; he began writing during World War II at the work camp to which he was relegated as a conscientious objector, and much of his early work decries the senselessness of war. In “Poetry,” he describes his vocation as both “a flower in the parking lot / of The Pentagon” and an “essential kind of breathing.”

Stafford has also been called a “nature writer,” though the term fails to capture his distinctive environmental vision. Throughout Ask Me—as I read that a heron is “the wilderness come back again, / a lagoon with our city reflected in its eye,” that “all animals have one soul,” and that “the world speaks everything to us”—I am reminded that Stafford’s life spanned the period between Transcendentalism and contemporary Ecopoetry, two movements in which his reflective environmentalism might have found some kindred voices. Yet, as Ask Me demonstrates, Stafford’s modes are manifold. One moment gentle and receptive, the next critical and morally imperative, his poetry is as textured and unpredictable as the natural world it so often extols. Uninterested in the moral relativism in vogue for much of his life—and unfazed by the critiques leveled by its practitioners—Stafford nearly always speaks with candor and moral authority: “What you fear / will not go away: it will take you into / yourself and bless you and keep you. / That’s the world, and we all live there.”

Still, we might ask what Ask Me adds to Stafford’s extensive bibliography. What makes it relevant to our twenty-first century literary and cultural climate? What can it teach us? The publication of Ask Me might signify an effort to distill Stafford’s prodigious (and, as Frederick Garber put it, “frequently uneven”) oeuvre to a few knockout poems, even eliding works that could complicate or contradict those included. In his attempt to show us something fundamentally Staffordian, the anthologist (in this case, the poet’s son) chooses which hallmarks to memorialize—at the necessary expense of some others. Yet I can’t help but agree with the book’s subtitle: these are “essential poems,” both insofar as they represent, to my mind, the themes with which Stafford dealt most, and because they speak candidly on subjects that preoccupy us to this day—maybe more than ever. Rooted in personal memories and strewn with proper nouns, Ask Me moves through youthful anecdotes, denunciations of war and environmental degradation, elegies and reminiscences about family members, Native American legends, and meditations on self-hood, art, tradition, and place.

“These Mornings” touches on several of Stafford’s central themes in his characteristic declarative, conversational verse:

Watch our smoke curdle up out of the chimney

into the canyon channel of air.

The wind shakes it free over the trees

and hurries it into nothing.

Today there is more smoke in the world

than ever before.

There are more cities going into the sky,

helplessly, than ever before.

The cities today are going away into the sky,

and what is left is going into the earth.

That is what happens when a city is bombed:

Part of that city goes away into the sky,

And part of that city goes into the earth.

And that is what happens to people when

a city is bombed:

Part of them goes away into the sky,

And part of them goes into the earth.

And what is left, for us, between the sky and the earth

is a scar.

If his country’s militarism and ecological footprint troubled Stafford in his lifetime, they would trouble him no less today. “These Mornings,” like many of the poems in Ask Me, is affecting partly because it relates so easily to current sociopolitical affairs that it seems almost prophetic. Even the more introspective poems (the famous “Traveling Through the Dark,” for example) are transhistorical, instructive; they exemplify something benevolent and finite about us all.

But it is not just the content of Stafford’s poems that warrants celebration. This was a man whose art, politics, profession, and connection to nature were integrated in an original and deeply embodied way of life. Stafford wrote and thought about the Big Stuff—love, death, connection, and legacy—when such abstractions were considered unserious and unscholarly points of inquiry. Ask Me reminds us that all Stafford’s critique (of warfare, pollution, and the institutions that condone them) serves an uncompromising idealism: a vision for peaceful coexistence with each other and the earth.