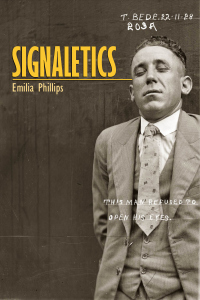

“Don’t ask where the teeth are / you exchanged for coins as a child,” advises Emilia Phillips in the opening poem of Signaletics, her first full-length poetry collection (University of Akron Press, 72 pages). But Phillips goes on to do exactly that: to root out the relics of childhood, and to recover systematically the physical residues of the estranged and the deceased. While the poems of Signaletics vary stylistically from dense prose sequences to neat series of couplets or tercets (including a sonnet), all address the material narratives we inscribe on our surroundings—with our fingerprints and possessions, lipstick stains and letters.

“Don’t ask where the teeth are / you exchanged for coins as a child,” advises Emilia Phillips in the opening poem of Signaletics, her first full-length poetry collection (University of Akron Press, 72 pages). But Phillips goes on to do exactly that: to root out the relics of childhood, and to recover systematically the physical residues of the estranged and the deceased. While the poems of Signaletics vary stylistically from dense prose sequences to neat series of couplets or tercets (including a sonnet), all address the material narratives we inscribe on our surroundings—with our fingerprints and possessions, lipstick stains and letters.

The book takes its name from a system of anthropometry conceived by Alphonse Bertillon at the end of the 19th century to identify criminal suspects. A signaletic assessment comprised measurements of the head, body, ears, eyebrows, and mouth, as well as scars, tattoos, and birthmarks. It is no wonder Phillips chose to base her collection on this method of bodily measurement—while she is obsessed with the body, her descriptions are usually more forensic than erotic, her narrator more coroner than esthete. In “Cross Section,” she writes, “One o’clock & B.’ s body / is now in the chamber where a magnet // will skim her ashes for screws, bone / fasteners, & crowns.” Like B.’s, the bodies that populate these poems are mostly absent, evinced only by what they have deliberately or inadvertently left behind. In her best poems, Phillips treats these remnants not as ontological byproducts but as autonomous bodies, possessed of secrets, stories, and spiritualized inner lives.

Further, nearly all the poems in Signaletics mention or apostrophize an absent father, presumably a forensic or criminological specialist himself, from whom the speaker inherits her fixation on physical records. In “Latent Print,” named for the term for an accidental fingerprint, Phillips writes:

If you’re ever kidnapped, bite

the car door, my father said one Sunday

after the divorce, Crown Vic en route

to his office. Teeth marks. I can find you

that way. Inside he sat me down & held

each of my fingers to an ink

pad, smothering ridges in black,

& then from left to right, prints

he rolled on a white card. These are yours—

they don’t change.

“If you’re ever kidnapped, bite the car door:” words that haunt the entirety of Signaletics, resonating through multiple poems about torn-out teeth and missing persons. Yet it is always the daughter doing the searching, sifting through keepsakes and time-altered memories for the father, distant and incommunicative in the Middle East. From his memorabilia (postcards from Iraq and Afghanistan, a jar of honey from Kurdistan, Kuwaiti bills), she assembles a post-hoc portrait of their relationship.

But if this book is preoccupied with physical traces, its most tragic moments occur in their absence. When a memory cannot be substantiated with material proof, the speaker must reckon with only “the dusky peat of ordinary memory.” The most arresting example occurs in “Vanitas (Latent Print),” about a dying brother:

The nurse’s ink would not do: so heavy it flooded

the ridges to smudge the white paper my father

pressed each of my brother’s fingers to. A record

wanted, the made engraving like shoe-tread on the steely

moon & into a pendant for his wife, N.’ s mother—

this, the last dotage, son to father. How impossible

creation was then, watching from my corner, as he bent

over the bed, my child-sibling paling in

lips & cheeks & hollowed chest, & darkening finally

across his backside, crown of his head, as the veins fractaled

indigo toward the empty ears. How long will you break me

in pieces with words? When my father, shaking & saying

over & over, This will not work—it’s too heavy, & wept again

as the ink wept from the sponge, the nurse at my request

brought an aluminum can to which we pressed the hands

for prints my father, unfathered, would lift later with dust.

*

I do not want to overstate Signaletics’ linear qualities or its correspondence to the poet’s life, nor do I want to overlook the steady, musical prosody of its verse. Phillips draws on a range of subjects, from battle reenactments and Bill Frisell to Cartesian automata and Arabic loanwords. Many of her poems are ekphrases, mostly in tribute to sculptures or defunct technologies: phonography, clepsydras, alchemy, pre-DNA forensics. Phillips is an ephemerist, infatuated by language’s ability to render the past “redrawn, resurrected, / which is, after all, the byword of memory….” And, just as her stylistic hybridity suggests a broad poetic heritage, Phillips’ literary allusions hail from all corners of the canon; Milton, Niedecker, “Ossian,” and Joyce all make appearances, as do lines from the Qur’an and the Bible.

These literary quotations seem to work like fingerprints: they can preserve a moment or even crystallize a life. For text, Phillips seems to attest, is as much a somatic residue as is a bloodstain—a physical remainder, a mimetic act in excess of the body. Maybe that’s what Signaletics is all about: leaving a paper trail of the poet’s own design, tweaking posterity’s memories of who Emilia Phillips was. As she asks in “The Study Heads,” if the remnants of the dead can cause us to react physically—can evoke our tears or nausea or laughter—“is this not a minor resurrection?”