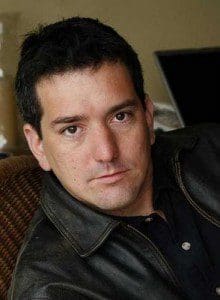

Born in Peru, and now living in Barcelona, author Santiago Roncagliolo was named as one of Granta’s Best Young Spanish-Language Novelists a few years back. Noted for being the youngest person to win the prestigious Alfaguara Prize (for his novel Red April, which was published in English in 2010), Roncagliolo is also a translator, a children’s book author, a newspaper contributor, and a soap opera writer.

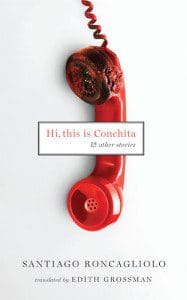

His past work has examined the horrors of the Sendero Luminoso in Peru as well as the sex trade in Tokyo, but in his latest book in English, Hi, This Is Conchita and Other Stories (Two Lines Press), a darkly funny collection translated by Edith Grossman, the settings are more familiar—the dull workplace, the tucked-away apartment, the day-time bus ride. Yet the tales are all the more enthralling for their seemingly prosaic environments, opening up worlds of desire, death, and dreams (or maybe it’s delusions?).

In the title story (told entirely in unattributed dialogue), empty sex, disdainful customer service, and a soured affair all unfold, and eventually dovetail, over the phone. “Despoiler” tells of a lonely Barcelona woman’s phantasmagoric evening out, a night seemingly populated by her beloved and long-lost stuffed toys. In “Butterflies Fastened with Pins” the serial suicides of friends plague a young man, and in the collection’s final story, “The Passenger Beside You,” a woman explains how the “enormous bullet wound in her heart” came about.

We spoke to Roncagliolo over email about his new story collection and his writing.

ZYZZYVA: You have been quoted as saying, “The way I work, I live things and then say OK, how can we make a story with this?” What if any experiences served as the springboard for the stories in Hi, This Is Conchita?

Santiago Roncagliolo: The title story was written a few years ago during a horrible summer. August in Madrid with no money can be hell. It was killing hot. And everybody—friends, girlfriend, family—were out of the city, having their holidays. I only had human contact by phone, and then my phone broke down.

Phones are very peculiar, you know? You talk into the ear of somebody, but you don’t see his eyes or touch his hands. You have to imagine the face of the person you talk with. I wanted that effect in that story. Like a screenplay with no images, just the words.

But this whole book is a black comedy about people being nowhere, looking for somebody out there.

Z: Why leaven in these tales, as you do, that deep sense of loneliness and alienation with humor?

Z: Why leaven in these tales, as you do, that deep sense of loneliness and alienation with humor?

SR: For me, humor has always been a defense against reality. I use it even for my political novels. Humor, mainly black humor, is the best way to talk about sad things, like loneliness, death, or loss.

Once I spent a night drinking and telling political jokes with two African writers. We had the same kind of jokes. The Europeans at our table were scandalized. They found our jokes very dark and cynical. But they hadn’t lived our experiences: crises, dictatorships, chaos. Sometimes, laughing is the only way not to cry.

Z: Reading “Butterflies Fastened with Pins” and “The Passenger Behind You,” I couldn’t help thinking of your background as a human right worker in Peru, plus your experience of living there during the time of the Sendero Luminoso. It seemed to me these stories try to convey what the constant presence of death is like, but presents it a more normalized, recognizable setting. Is that accurate?

SR: It sounds at least quite possible. “Butterflies” is really a chronicle. I actually had seven friends that committed suicide. It seemed like an epidemic. I guess that was not normal for a twenty-year-old. Somehow, I suppose, it had something to do with the violence we were living with in the country.

Z: Speaking of which, what can or should a fiction writer do when addressing the subject of corruption and violence that accompanies the abuse or competition for power? I’m thinking here about Peru under Fujimori, or even civic life right now in contemporary Mexico. What can a work of literature hope to do?

SR: Make your readers feel. If they feel the rage of injustice, or the fear of violence, maybe they get inspired and try to change those things.

Z: For a while your family had to live in Mexico, but eventually returned to Peru. What were the circumstances around that? And what eventually led you to Barcelona?

SR: My father was exiled by the Peruvian dictatorship when I was a kid. And México at the time was receiving left wingers from the whole of Latin America. We went back to Perú with the return of democracy there. Many years later, as an adult, I emigrated to Madrid because I wanted to be a writer. Six years ago, I met a wonderful woman on a bus in Barcelona. And here I am.

Z: You have translated several English-language writers into Spanish, including Joyce Carol Oates. What sort of work do you seek out to translate, or are those commissioned jobs?

SR: I am lucky. I propose what I want to translate. Usually publishers accept. I wanted Joyce Carol Oates because I loved her novel Beasts. It is like a horror story but totally realistic. No ghosts or monsters. Just human emotions. And very scary. For my work, I have the best translator: Edith Grossman. I am sure I am a better writer in English than in Spanish because of her.

Z: One last question: What did writing children’s books and soap opera scripts teach you about writing “literary” fiction? The importance of story? Of making sure the reader is entertained even while being enlightened?

SR: All that and more. I love popular culture. Always have. I make stories with the materials writers usually throw into the garbage. I do not understand why a great filmmaker like Stanley Kubrick can make comedies and science fiction movies, but a writer is forced to be a realist and to be serious to be “respected.” It just makes no sense. I don’t want to be the president. What I enjoy is freedom and creativity.