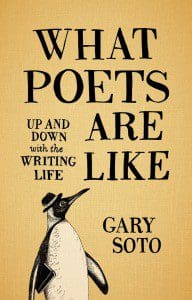

For some reason—the imperative-sounding title, perhaps?—it’s easy to imagine a would-be poet leafing through What Poets Are Like: Up and Down With the Writing Life (Sasquatch Books; 236 pages), in expectation of a how-to guide. Such ventures will be somewhat disappointed, at least at first. Gary Soto’s collection of short, autobiographical essays are highly particular and personal, specific to Soto himself. And Soto’s wry, occasionally self-deprecating sense of humor means that, far from extolling the virtues of leading a writer’s life, many of the pieces contained in this collection point out its travails, its small indignities for anyone less of a “big shot” than Stephen King or John Grisham.

For some reason—the imperative-sounding title, perhaps?—it’s easy to imagine a would-be poet leafing through What Poets Are Like: Up and Down With the Writing Life (Sasquatch Books; 236 pages), in expectation of a how-to guide. Such ventures will be somewhat disappointed, at least at first. Gary Soto’s collection of short, autobiographical essays are highly particular and personal, specific to Soto himself. And Soto’s wry, occasionally self-deprecating sense of humor means that, far from extolling the virtues of leading a writer’s life, many of the pieces contained in this collection point out its travails, its small indignities for anyone less of a “big shot” than Stephen King or John Grisham.

This would be depressing to read if it weren’t for Soto’s comic timing and charming prose, which is carefully crafted to allow as much of his personal idiom and character as possible onto the page. Soto’s focus on intimate details is poignant at times, delightful at others, but always used to great effect while constructing a scene. These small brushstrokes are often domestic—such as the heavy, broad-shouldered maroon overcoat, hand-sewn by Soto’s wife, that he wears to a 49ers game in his essay “The Winning Crowd” (which appeared in ZYZZYVA Issue No. 93), or the sick dog he remembers feeding with a spoon in his youth in “After Reading Six Pages From The New Testament.”

There are a few persistent threads tying together Soto’s essays—dogs and snappy dressing, the idea of community (most of the essays take place either in Berkeley, Soto’s current home, or his hometown of Fresno), and the Mexican American experience, of which he has many different stories to tell. In “Flat Tire,” Soto describes being helped by a young field worker who remembers hearing him speak at a school assembly, down to the silly little jokes Soto himself has forgotten; in “Book Signings,” he encounters a reactionary reader who questions him sarcastically (“what has been your contribution to Chicano literature?”); and in “Pooch, Who Are You Named For?”, Soto meets a teacher and huge fan who’s named her dog after him. Smiling, she tells him it’s a “Chihuahua, of course!”

But the biggest link among the essays is Soto’s voice itself, which is lively and funny and present, especially when Soto is making self-deprecating references to the youth of today. (In “Party Talk,” Soto confesses to a young female acquaintance that he’s never owned a cell phone. “Like, what?” she exclaims. “What if people want to, like, talk?”) It’s impossible not to picture Soto settling winkingly into the role of the grumpy old man, though he’s only 61.

Soto’s keen sense of opening and closing lines that are surprising yet true adds to the sensation that the reader is carrying a one-sided conversation with Soto (or perhaps more aptly, listening to his stories). In the opening essay, “Aging Poet,” Soto begins: “I cancelled my love for the dog when he yawned while I was reciting a poem.” Soto’s deft ability to wrap up a piece so it lingers poignantly is an uncommon one, and is shown off to great effect in most of these brief but widely ranging pieces—from subjects like Cesar Chavez and Soto’s favorite instances of poetic rebellion (such as the English public school student who when told by his schoolmaster that masturbation causes blindness asked if he could “do it just till [he’s] farsighted”) to the many students he’s taught and his beloved wife, Carolyn.

It is perhaps in this way these short prose pieces most resemble Soto’s poetry—self-enclosed and highly imagistic, turning on particular details in his life. As Soto says on his website’s FAQ: “as a writer, my duty is not to make people perfect, particularly Mexican Americans. I’m not a cheerleader. I’m one who provides portraits of people in the rush of life.” It seems this applies to his self-portrait, too.