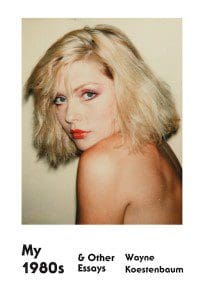

Poet and critic Wayne Koestenbaum’s newest book, My 1980s & Other Essays (320 pages; Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), brings together a wide range of enthralling and intellectually daring texts, ranging from rigorous critical explorations of Susan Sontag and John Ashbery to a diary-style look at the life and work of Lana Turner. The essays vary wildly in length and subject, but are grouped together, vaguely, by theme: the first section contains the closest thing to traditional “personal essays”; the second section tends toward literary critique; the third one toward cinema, celebrity, sex; and so on. Each section feels like a well wrought, carefully tended representation of some part of Koestenbaum’s thought, some edge of his oeuvre, but taken as a whole, the collection appears captivatingly off-kilter. My 1980s is a work in motion, unstable, to be read in tight, short bursts or languorously, as a long, ruminative drift through the work of a powerful creative and intellectual force. But Koestenbaum himself—his voice, his language, his particular blend of sarcasm and seriousness, his “I”—is always at center, lending a delicately tied sense of self to a collection that is quite purposefully against absolute cohesion.

Poet and critic Wayne Koestenbaum’s newest book, My 1980s & Other Essays (320 pages; Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), brings together a wide range of enthralling and intellectually daring texts, ranging from rigorous critical explorations of Susan Sontag and John Ashbery to a diary-style look at the life and work of Lana Turner. The essays vary wildly in length and subject, but are grouped together, vaguely, by theme: the first section contains the closest thing to traditional “personal essays”; the second section tends toward literary critique; the third one toward cinema, celebrity, sex; and so on. Each section feels like a well wrought, carefully tended representation of some part of Koestenbaum’s thought, some edge of his oeuvre, but taken as a whole, the collection appears captivatingly off-kilter. My 1980s is a work in motion, unstable, to be read in tight, short bursts or languorously, as a long, ruminative drift through the work of a powerful creative and intellectual force. But Koestenbaum himself—his voice, his language, his particular blend of sarcasm and seriousness, his “I”—is always at center, lending a delicately tied sense of self to a collection that is quite purposefully against absolute cohesion.

“Autobiography is not a defunct practice,” Koestenbaum writes in “Play-doh Fun Factory Poetics,” an essay that explicates beautifully the author’s “anal, alimentary, abstract” poetics, which extend, deliriously, into his work with the essay. In the autobiographically tinged essay, Koestenbaum finds a space outside of the academic addiction to earned authority, a space in which free-associative creativity and genuine affect can be brought to the fore along with the development of “serious” intellectual thought, in which unreliable testimony can deepen and intensify poignant cultural critique.

Quite appropriately for a collection of essays penned by an oft-published poet, one of the first things one notices in My 1980s is the author’s undeniable grip on the English language. Koestenbaum’s charmingly enormous vocabulary can propel an essay by itself: one simply can’t wait to see what wonders will be worked with words next. Rarely used lexicographic gems like “demesne” and “perineum” (“Thanks, by the way, for pointing to your perineum,” Koestenbaum writes in “Dear Sigmund Freud,” the shortest essay in the collection), are rolled out to articulate the author’s passionate devotion to the exploration of forgotten zones, the aesthetics of neglected space. While Koestenbaum tends toward minute description and precise critique, he also revels in the absolute “polysemy” of language, allowing the room for the double (or triple) meaning of “escutcheon-like” to proliferate. My 1980s is often as much about celebrating the spectacle of the language used to describe things as it is about the things themselves.

Perhaps the highlight of the collection is “In Defense of Nuance,” in which Koestenbaum energetically articulates his attraction to the work of Roland Barthes, particularly A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. In the essay, Koestenbaum identifies his particular affinity to Barthes as stemming from a shared admiration for “nuance,” for that which is “beyond detection, beyond system.” Koestenbaum claims that Barthes’ Lover’s Discourse is an attempt to “filibuster Meaning and prevent it’s tidy consumption,” a description that could certainly be attached to My 1980s as a “complete” collection. “In Defense of Nuance” stands out from the rest of the collection partly because it seems to be situated as a sort of explanation for the methodology of the whole while simultaneously dismissing any such possibility. Koestenbaum notes this same stuttering, self-consuming synecdochical tendency in Barthes:

“Throughout the book, Barthes makes spasmodic approaches to coalescence—rapid, flickering bursts of volcanic cerebration, sculpted into gnomic phrase-clusters, the interrupted clauses linked by a series of colons, colon after colon::::: an unforgiven plethora.”

As Koestenbaum’s intellectual and emotional excitement reaches a boiling point, his syntax doesn’t so much dissolve as evolve: for Koestenbaum at his peak, language bends and breaks ecstatically.

My 1980s is perhaps at its weakest when the usually (pleasantly) overabundant “Koestenbaum” fades into the background. In “Epitaph on Twenty-Third Street,” a meandering meditation on the poetry of James Schuyler, Koestenbaum the writer is more or less swallowed up by his devotion, his ecstasy at the work of another writer dampening the reader’s interest rather than exciting it. Another, much shorter essay, “Schuyler’s Colors,” tackles the poet’s art criticism. Schuyler is the only figure who is the subject of two essays, and “Schuyler’s Colors,” the shorter of the two—and the one not focused on the texts for which Schuyler is largely known—proves far more engaging. Here, Koestenbaum’s dedication to nuance, to “the third meaning,” as Barthes wrote, seems to be justified, appropriately, despite himself.

From one essay to the next—from one page or even one sentence to the next—Koestenbaum’s text shifts and skips, taking the form of a mock dialogue between artist and subject here, appearing as a list of strange “Assignments” there (“write about a color without mentioning its name”). In “Advice to the Young,” Koestenbaum—in an almost indiscernible tone that mixes absolute irony and up-front ingenuousness—conjures up scenarios from his youth to transmit apparent lessons. “Much about myself I can’t change, even if I tried,” he writes, “and so I try to present the flaws as starkly as possible.” My 1980s feels, at times, like a collection of flaws magnified, turned inside out, investigated. In “The Inner Life of the Palette Knife,” Koestenbaum notes that the monochromatic sections of the works of little-known painter Forrest Bess prove the most interesting, their surfaces scarred and ripped by the strokes of the artist’s palette knife. My 1980s seems to suggest that our personal flaws, our failings and shortcomings, are perhaps akin to Bess’ monochromes or Freud’s perineum: dejected or rejected zones, distinguished apparently by their slightly offensive banality, holding within the key to a more ecstatic and passionate engagement with the world.