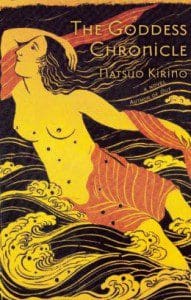

Japanese crime writer Natsuo Kirino’s latest novel, The Goddess Chronicle (Canongate; 312 pages) translated by Rebecca Copeland, is a revenge-filled rethinking of an ancient Japanese creation myth. As the latest entry in The Canongate Myths series, Kirino’s novel reinterprets aspects of the Kojiki—a collection of myths initially assembled in eighth century Japan—to tell the story of two powerful deities, Izanami and Izanaki, and the beginning of the world.

Japanese crime writer Natsuo Kirino’s latest novel, The Goddess Chronicle (Canongate; 312 pages) translated by Rebecca Copeland, is a revenge-filled rethinking of an ancient Japanese creation myth. As the latest entry in The Canongate Myths series, Kirino’s novel reinterprets aspects of the Kojiki—a collection of myths initially assembled in eighth century Japan—to tell the story of two powerful deities, Izanami and Izanaki, and the beginning of the world.

This origin story is not a happy one: the world produced by Izanami and Izanaki is born of conflict, through an infinite cycle of betrayal and payback. For every one thousand people killed daily by Izanami—the female goddess of the dead—Izanaki attempts to produce fifteen hundred new lives in fifteen hundred “birthing huts.” This infinite conflict between these former lovers comes about because Izanaki abandons Izanami after her death, leaving her trapped forever in the realm of the restless dead. The Goddess Chronicle relays this complex tale in sparklingly clear—if at times too spare—prose, rendering a dark story into a surprisingly lively read.

The Goddess Chronicle begins with the story of one of Izanami’s priestesses, Namima, a deceased sixteen-year-old who helps the deity with overseeing the realm of the dead. She and the goddess have a special connection, their status as betrayed women bringing them together. Born on Umihebi, a tiny, remote island the shape of a teardrop, south of Honshu, Namima is fated at birth to become the island’s priestess of the dark. Her older sister, Kamikuu, must become the next Oracle, the priestess of the light. Before they gain their positions, the girls are separated and receive training apart from each other, and the nature of Namima’s fate—to stand vigil, alone and until her death, over the island’s dead—is kept secret from her. When the two women finally do take over their respective positions, Namima does so with a secret: she is pregnant with the child of the man to whom her sister wants to wed. The couple try to escape the island on a small boat, on which Namima gives birth, but soon after dies (how she dies is one of the great surprise twists in the novel—one of many). She then enters the palace of the dead, and the story of Izanami and Izanaki begins.

Trapped in the realm of the restless dead, Namima learns the origins of her world (and thus the origins of her suffering) from Izanami and from a dead storyteller charged while living with memorizing early Japanese myth—Hieda no Are. (Are is a historical figure from whose recitations from memory the Kojiki is thought to have been assembled. In The Goddess Chronicle, Are appears as a woman, but her gender is one of the many details contested in contemporary study of the Kojiki. Her presence in Kirino’s text as a woman is quite purposeful, and feels consistent with the novel’s devotion to the figure of the woman as originary).

Here, in the midst of The Goddess Chronicle’s most beautifully described setting, Izanami’s palace of the dead—an infinite tomb, both ceilings and walls extending infinitely into darkness—the novel delves fully into its source text, turning completely toward the telling of epic myth. Are’s telling of the origin story includes fascinating mythic explanations for minor traditions and customs, as well as proverb-like summations: “The sword is born from fire, and the right to fire is controlled by the sword.” In the realm of the dead, the novel is at its engrossing best: a creation myth of stunning clarity told to those whom creation has betrayed.

The Goddess Chronicles does, however, falter at points, though the particulars in which it falls short are difficult to talk about in a nuanced way. From a “literary” standpoint, its prose is often flat, and many characters are left equally flat and undeveloped. But when taken as a re-imagining of a myth, these weaknesses appear to be merely conventions of the form. (That is, if it can really be said that there is a convention to “the form” of the myth: it is perhaps more appropriate to say that there are conventions to the form of the modern retelling of myth in which myths are simply “stories” rather than directives to live by, morality tales, or explanations of seemingly unexplainable phenomena). The writing, particularly the images used, can at times approach cliché, but it is hard to fault a myth for appearing that way. (Where else does cliché come from?) Over the course of about three hundred pages, though, the familiarity of the imagery is at times hard to forgive, such as when we find a character peering “hard into the darkness […] tears glittering when they caught the moonlight.”

The Goddess Chronicle, however, is an extraordinary re-telling of one small piece of a body of myth often overlooked in the West. The myths and rituals described in the Kojiki are part of the inspiration for Shinto as it is practiced—by millions of people—in modern Japan today. Kirino’s novel serves as a fascinating, approachable introduction to an ancient body of myth, thought, and ritual. Anyone curious about the history and traditions of the world’s tenth largest country would be wise to investigate it.