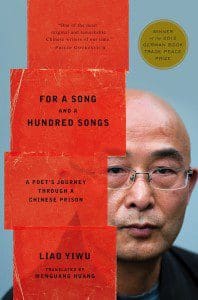

Violently quashed protests, wrongful imprisonment, book banning, torture—these acts have become almost expected within the context of political rebellion and its suppression. The painful, familiar components of modern repression are given new perspective, however, in Liao Yiwu’s memoir and new book, For A Song And A Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison (New Harvest Press; 404 pages), translated by Wenguang Huang.

Violently quashed protests, wrongful imprisonment, book banning, torture—these acts have become almost expected within the context of political rebellion and its suppression. The painful, familiar components of modern repression are given new perspective, however, in Liao Yiwu’s memoir and new book, For A Song And A Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison (New Harvest Press; 404 pages), translated by Wenguang Huang.

In his book, Yiwu, a Chinese poet, tells the story of his time in prison following the Tiananmen Square protests of June 4, 1989. Though not a protestor or even, as he admits, particularly interested “in mass movements or foreign imports such as democracy, freedom, human rights, and love” before Tiananmen Square, the events of June 4 changed him, as they changed all of China. Upon realizing “art was my protest,” Yiwu began writing government-indicting poetry, notably the poem “Massacre,” and produced a politically charged film, Requiem, alongside other counterculture literary friends. Yiwu and his colleagues were utterly unaware, though, of how closely their movements were being monitored, and one day, as Yiwu boarded a bus bound from his city of Fuling to Beijing, where he intended to screen Requiem before a wider audience, he’s detained by the police and taken to jail.

From this point on, For A Song details, often brutally, the realities of life for Yiwu as a political prisoner in China. Upon arriving at the “investigation center,”,Yiwu is introduced to the prison’s hierarchal system, wherein one long-term prisoner acts as a domineering “chief” over both the higher- and lower-ranking “thieves” (the prisoners’ term for one another). “In my cell,” Yiwu writes, “which was no bigger than two hundred and twenty square feet for eighteen men, the rulers had created an exact replica of the state bureaucracy outside.” When he refuses to go along with his chief’s elaborate and sadistic hazing system (new prisoners are made to sleep naked, crammed tightly among other low-ranking prisoners; a punishing prospect during the summer), he’s introduced to the “menu” of various tortures new prisoners were expected to choose from if they disobeyed an order. (For example: “Twice-Cooked Pork on an Iron Platter: The enforcer stabs the inmate’s back with bamboo sticks and spreads salt on the puncture wounds. He covers the wounded area with adhesive bandages. Once the bleeding stops, the bandages are ripped off, leaving the flesh on the inmate’s back looking like cooked meat.”) His days pass in a haze of violence and interrogation. Yiwu remains imprisoned for the next four years for the crime of having helped create a “counterrevolutionary” film.

By the time Yiwu is freed, he’s gone bald and has physically deteriorated; his young daughter doesn’t recognize him and is terrified of the strange new “bad man” in her house, while his wife wants a divorce; and the government has destroyed all existing copies of his books and poetry.

This is grim stuff, but even when Yiwu is literally cataloguing evils, such as the five pages listing the torture menu, his story never seems melodramatic, thanks to the book’s matter-of-fact language and its unembarrassed, unpretentious recounting of prison. “I am not capable of elevating human feces to a higher level and imbuing it with political, historical, and religious meaning,” Yiwu writes. “In this ordinary memoir of mine, shit is shit. I keep mentioning it because I almost drowned in it.” Such straightforwardness is refreshing, if perhaps slightly disingenuous (in Yiwu’s writing, feces and other bodily waste and fluids certainly do operate on multiple levels).

But a little more extrapolation would have been welcome toward the end of the memoir, when Yiwu re-enters the “real” world and has to navigate family life once more. Yiwu hints at but never makes explicit an entire other narrative about his family and its destruction because of his time in prison. (He and his wife were divorced in 1994, and he has not seen his daughter since their separation.) He does acknowledge in the first chapter that he was a fairly bad husband to his wife (like most of the poets in his circle, he was a philanderer and a wanderer who’d leave the house without warning to travel), so it’s possible to see how the splintering of his family might have occurred even without the separation of prison. But this is a minor concern. Overall, For a Song and a Hundred Songs is compelling, pertinent material, perhaps more so now than even twenty years ago.