There’s a lot of good writing out there—an amazing amount, really, considering the ongoing moaning and groaning going on about the “death of literacy’’ and other current cultural shibboleths—but not that much that is truly original, free of clearly demarcated literary influences, antecedents and referents.

There’s a lot of good writing out there—an amazing amount, really, considering the ongoing moaning and groaning going on about the “death of literacy’’ and other current cultural shibboleths—but not that much that is truly original, free of clearly demarcated literary influences, antecedents and referents.

A thousand Eggers, David Foster Wallaces, let alone Kerouac and Salinger imitators, bloom from every Brooklyn basement and suburban redoubt. All the more remarkable, then, when someone finds a way to make it new, speaking her own truths against the powers of the past.

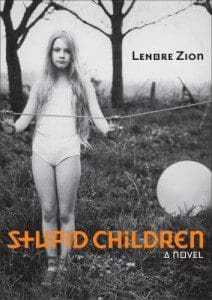

Which makes Los Angeles author Lenore Zion’s first novel, Stupid Children (Emergency Press, $15.95), all the more remarkable.

“According to my father, he was assigned a grief counselor when my mother died,’’ she begins. “It was sudden—an unanticipated death, and he was left to care for me all on his own—and I was just an infant, seven months old, actually, so his grief was fueled by both loss and overwhelming responsibility. From time to time, I feel rather guilty about this. I wish I could have been older so I could have pitched in. Maybe I could have gotten a job to help out.”

Jane, Zion’s fictional protagonist, is wise beyond her years, a smart-ass struggling to find her way in a confusing, and often frightening world, as her father struggles with his own loneliness, sometimes waking her in the middle of the night so they can go to a diner for an early breakfast. The world becomes even scarier—much scarier—when he attempts suicide, leaving her in the hands of two Florida foster parents who belong to a cult called Second Day Believers, whose belief systems could find a comfortable home amid the followers of Jim Jones or the farther reaches of Scientology.

Among other practices, the group believes in “cleansing’’ mental impurities from the young by inserting “two deflated, worm-shaped balloons’’ into their noses, breaking them as collateral damage.

“After the procedure, or as they called it, the ‘ceremony,’ I curled into my bed, beneath the disorienting black ceiling, cotton stuffed into my nostrils, eyes clinging to the nightlife I had brought with me from my real home, terrified, my mind unquestionably more plagued by demons than before,’’ Zion writes.

Despite the Southern Gothic nature of the material (there’s also an initiation ceremony in which Jane is dunked for a “healing swim’’ in an indoor pool with the intestines of farm animals), the author retains a sense of humor about the experience, noting dryly that “regardless of the spiritual benefits I was promised from this particular cleanse, I really would have preferred to retain my Judaism.”

Despite the nature of the material, Stupid Children has none of the implausible affectations of, say, Augustin Burroughs, or James Frey. The narrator, and the author, seem closer to the authentic characters who populate the world of Flannery O’Connor. Jane is a child struggling to grow into adulthood while retaining her innocence, against all odds, and her saving grace is honesty. Forced into group therapy, with an emphasis on (very early) sex education along with other cult members, Jane holds on fiercely to the truth, whether or not it’s calculated to set her free:

“Now, in class, another girl, one sitting in her fucking chair like a reasonable human being, was babbling about how much she loved children. This was Tanya, a fifteen-year-old girl…”

Asked to “participate.” Jane replies:

“ ‘I don’t care for children,’ I said, angry eyes pointed at the ground. ‘I find it especially frustrating to interact with stupid children.’ …

” ‘There’s no such thing as a stupid child,’ Tanya said.

“The rest of the group was demonstrating body language making it clear that they, too, were appalled that I used the word ‘stupid’ in the same breath as the word ‘children.’

“ ‘Of course there is such a thing as a stupid child,’ I said. ‘Stupid adults start off as stupid children.’

“ ‘That’s not true,’ Luke said.

“ ‘And before that, they are stupid infants,’ I said.

“ ‘How can you be so judgmental?’ Luke asked me.

“At this point, I was forced to explain to everybody that there was a mean of intelligence, and that this mean existed because a certain percentage of the population (fifty) fell beneath it.

“ ‘That’s why they call it a mean,’ I explained.”

Jane’s unrepentant ways lead to a rebirthing/puberty rite in which she is sewed up inside the belly of a dead cow. When she emerges, claiming that she has the spirit of a bobcat, she is primed to replace the late wife of Sir Number One, the leader of the cult.

Lucky girl.

“I didn’t think about what marriage would be before I got married,” Zion writes. “I’d been fighting for six years and I was tired…I’ve been told by Dr. Green that this death of the fighting spirit at such a young age is uncommon—most sixteen-year-old girls love to engage in battle. They thrive on it. I suppose the battles I fought were selected for me, without my input, and this is why I grew weary of quarreling at such a young age.

“This is not to say that I think I had it harder than a normal sixteen-year-old girl who was leading a crusade against her parents for a later curfew—I have no idea what that normal girl’s life is like…The standards were lower for a girl in my position, thus granting me a higher threshold for abuser tolerance. If your father cuts his throat open and the foster family system very thoughtfully assigns you a foster family heavily involved in a cult that makes a habit of treating their young like meat puppets, you become accustomed to disappointment rather quickly.”

For those of you who’ve stayed this long, here’s a welcome program interruption:

Reader, she gets away from them.

But not before embarking on some near-escapes with her sexed-up girlfriend, Virginia, and a zombie-loving fellow foster child named Isaac, and some side trips into the joys of cutting and the dangers of impulsively agreeing to tattoos.

Zion, whose author’s bio lists her, deliciously, as a clinical psychologist with a specialty in sexual pathology, focusing on “exhibitionism, pedophilia, fetishism, sadism, masochism and frotteurism,” ends her coming-of-age tale in a cadenza of expiation worthy of Tarantino, or the morning’s newscast. It is not Jane who wreaks revenge against her oppressors, though they richly deserve it, but her over-medicated pal, Isaac.

She survives, literally bloody but unbowed.

“I suppose it’s hard to say what my day is like now,” the narrator says. “The days begin, I do things I like, and they end. Summarizing a series of nightmares is simple, I’ve noticed—it’s much more challenging to describe the parts of life that prove my father was right all along, that there is beauty and wonder—sometimes you just have to wade through the mire before you are offered the light.”