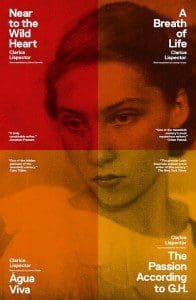

In his preface to Clarice Lispector’s A Breath of Life (Pulsations), editor Benjamin Moser calls the four new translations from New Directions of Lispector’s novels—including Água Viva, Near to the Wild Heart, and The Passion According to G.H.—“the most important project of translation into English of a Latin American author since the complete works of Jorge Luis Borges were published a decade ago.”

In his preface to Clarice Lispector’s A Breath of Life (Pulsations), editor Benjamin Moser calls the four new translations from New Directions of Lispector’s novels—including Água Viva, Near to the Wild Heart, and The Passion According to G.H.—“the most important project of translation into English of a Latin American author since the complete works of Jorge Luis Borges were published a decade ago.”

This is hardly a disinterested opinion: Moser himself kicked off the retranslations of Lispector’s work with The Hour of the Star (New Directions), published late last year. He also published a biography of Lispector in 2009, Why This World (Oxford University Press). But as someone who shares his esteem for her writing, I understand Moser’s evangelical ardor. I also agree with his assessment. Three of the titles gathered here are the most vaunted novels of Lispector’s literary career. The fourth, A Breath of Life, is Lispector’s last novel, published a year after her death from ovarian cancer at age 56. Her masterpiece is undoubtedly among them, although critics will never agree about which one of these it is.

The aforementioned preface to A Breath of Life is in fact an epistolary exchange between Moser and Spanish film director Pedro Almodóvar, whom he solicits to write the novel’s opening remarks after being struck by similarities between Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In and Lispector’s final novel. Their correspondence is published in lieu of a preface, which the director declines to write. This is not because Almodóvar dislikes the text. On the contrary, he explains that the book interested him too much.

This is not surprising: Lispector’s novels have a reputation for creating obsessed readers. Hers is a rapturous, delirious prose that goes down like a treacly drug. Lispector’s narrators often compare themselves to composers, rather than filmmakers, and for good reason. The author’s penchant for paradox, chiasmus, and tautology lends her narrators’ voices an eerie musicality. The hypnotic rhythms of Lispector’s prose seduce her reader into a spiritual reverence for madness. “I took refuge in madness,” her final narrator explains, “because reason was not enough for me.”

Lispector’s prose is often unsparingly brutal, and each of these novels forms part of her extended inquiry into “the inhuman.” By this she refers to that which escapes the “humanization” of rational or logical thought: the primal and the savage, but also the divine. To experience the inhuman, her narrators strive for a radical shift in consciousness that allows for visceral and epiphanic encounters with the material world. In her writing, Lispector often tropes the inhuman with actual animals: “This is not a lament,” begins A Breath of Life, “it’s the cry of a bird of prey.” Likewise, the protagonist of Lispector’s semiautobiographical debut, Near to the Wild Heart, is condemned as a “viper” for being a woman too wild to be caged by marriage. Jaguars and dogs also proliferate in Lispector’s work; in The Passion According to G.H. it is the cockroach that enjoys paramount importance.

Lispector seemingly longs to be one of these inhuman beings. “In my core I have the strange impression that I don’t belong to the human species,” confesses the narrator of Água viva, “Not having been born an animal is a secret nostalgia of mine.” But since capacity for language is what separates the human from the animal, she must make do with it in her own savage way. Like her character Angela Pralini, Lispector “gives herself the luxury of being sphinxlike,” reveling in the poetics of her narrators’ mystic explorations until the time is right to strike.

Her attacks are often directed at language itself, and on the spiritual precariousness of any life premised on logic. Based as it is on the logos—the word—logic is forever vulnerable to being cast into the great beyond of irrationality denoted by paradox, mise-en-abîme, and other specters of linguistic nonsense. “I don’t want to have the terrible limitation of those who live merely from what can make sense,” the narrator of Água viva asserts. “Not I: I want an invented truth.” It is the primal, illogical experience beyond thought that Lispector and her protagonists crave.

This truth comes at the price of a pained ecstasy, testing the boundaries of madness and the limits of the written word. To get beyond thought is the ongoing project of Lispector’s literary work, beginning with Near to the Wild Heart (1943) and culminating in the kabalistic pair of novels Água viva (1977) and A Breath of Life (posthumously published in 1978). Her objective as a writer was to surprise herself with what she’d written. The results repeatedly stunned readers and critics for the three decades Lispector wrote, as they continue to do today. Accompanying this otherworldly and cultish writing was the personage of Clarice herself, who relished her reputation as a bewitching and unsettling woman. In one of her most notorious exploits, Lispector appeared as a guest of honor at the First World Congress of Sorcery in Colombia. Lispector now enjoys mythic status in Brazil, where she is regarded as the unrivaled high priestess of Brazilian letters.

It is odd, then, that despite the fanaticism her work inspires in Brazil and France, Lispector remains little-known in the Anglophone world. These translations will likely change that, but not because the novels were previously unavailable in English: only A Breath of Life appears in translation for the first time. Instead, this quartet replaces the first English translations of Lispector’s work carried out in the late 1980s. The chief difference between them, as far as I can detect, is the effort made by the new translations to allow the bizarreness of Lispector’s Portuguese diction to carry over into English. A deftness of vocabulary, characteristic of Lispector’s Portuguese, also marks these new translations.

Because Americans read far fewer works in translation than Europeans, nervous publishers feel obliged to persuade their audiences. Attempts to describe Lispector’s prose thus lapse into spurious comparisons, with dust-jacket blurbs associating her with figures as diverse as Joyce, Woolf, Kafka, Sartre, Gertrude Stein, and J.M. Coetzee. The likeness to Kafka makes the most sense, as it connects Kafka’s uncanny sublime to Lispector’s gnostic search for understanding. But as Michael Wood observed when confronting one such blurb—comparing her to Katherine Mansfield, Camus, and Chekhov—it is hard to discern family resemblances among such a motley crowd of literary cousins.

Virginia Woolf is the most insistent comparison offered for Lispector’s work. This is due largely to a remark made by Gregory Rabassa, who translated her 1961 novel, The Apple in the Dark. Rabassa called Lispector “that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.” But Lispector’s writing doesn’t resemble Woolf’s all that much. And when have the resemblances of male writers ever been of importance? Do we care that William Faulkner didn’t look like Clark Gable? Following her debut, some in the Brazilian literary community found it hard to believe that a striking diplomat’s wife could write so exquisitely, and assumed her unusual foreign surname was the pseudonym of a male author. (In fact, she was born as Chaya Pinkhasovna in Ukraine in 1920. Her Jewish parents fled from there for Brazil in 1921.) The Woolf connection also conjures the famous line from A Room of One’s Own: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” At twenty-two and having neither, young Clarice had needed to shut herself away in a small rented room to finish writing Near to the Wild Heart.

Rabassa, along with everyone else who compares Lispector to European modernists, inadvertently makes an amusing point about Brazilian literature. One of the most celebrated texts of Brazilian modernism is Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 “Cannibalist Manifesto,” which, while riffing on European stereotypes of Brazilian barbarism, advocates for the superiority of cultural production that omnivorously consumes foreign influences. The Brazilian modernists ate their helpings of Joyce, Mallarmé, and Dostoevski. Lispector was no different. And as the reader of The Passion According to G.H. will learn, quite memorably, Lispector ate her Kafka, too.

Since Lispector’s death, the overwhelming critical stance is to read her as feminist and to regard her work as intensely “feminine.” We owe this oversimplification to the outsized influence of Hélène Cixous, who made Clarice Lispector the standard-bearer for her concept of écriture feminine. Written with the white ink of woman’s milk and the nonlinear verve of intuition, écriture feminine privileges the body over the mind. It is true that Lispector was fascinated by the perceptive capabilities of the body. “If here I must use words,” the narrator of Água viva writes, “they must bear an almost merely bodily meaning. I’m struggling with the last vibration…Read, therefore, my invention as pure vibration…” But this is where the contradiction appears: Lispector’s writing, while concerned with the bodily intuitive, is also intensely cerebral and spiritual. It is precisely the body–mind dichotomy that Lispector sought to overturn.

Readers of these four novels will understand why it is futile to categorize a writer as unusual as Clarice Lispector. The narrator of Água Viva also speaks for the author on this account: “No use trying to pin me down: I simply slip away and won’t allow it. No label will stick.” This literary singularity was a constant in Lispector’s career. The debut of “Hurricane Clarice,” as writer Lúcio Cardoso called her, was met with thunderous praise in Brazil. Titled after a line from Joyce, Lispector’s first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, drifts between third- and first-person narrations of three different characters. It centers on Joana, a young orphan who spooks her caretakers and later intimidates her husband with her intellectual and moral independence. The narrative’s indifference to linearity and its near-exclusive interest in introspection prepare the reader for Joana’s final sinking “into the incomprehension of herself.”

With the possible exception of Near to the Wild Heart, translated by Alison Entrekin, none of these novels has any plot to speak of. Instead, their narrative diagrams read like fever charts of each narrator’s struggle with the limitations of expression and the quest for artistic transcendence. For instance, almost nothing happens in The Passion According to G.H. Instead, the entire novel is the narration of an epiphany experienced by the protagonist—a sculptor known only by the initials on her suitcases—on the morning after she fires her maid. But the one thing that does happen is so astonishing that New Directions can rightly get away with calling it “Lispector’s most shocking novel.” Suffice it to say that what happens is an unforgettable, blinding stroke of genius: even if The Passion According to G.H. were Clarice Lispector’s only novel, she would be no less mythic an author.

While The Passion is a gnostic search amid an existential darkness, the painter that narrates Água viva adopts the tone of a woman already possessed by the light of truth. It is here, in this zone of bewitched lyricism, that Lispector rises to the height of her power. Água viva, along with A Breath of Life, are experimental “fragmentary” novels, written as bursts of inspiration and connected by Lispector’s philosophical inquiry into human existence. The painter who narrates Água viva wants to capture the essence of the “thing itself,” so she turns to the written word to explore jazz-like improvisations on the “instant”: “I know what I am doing here,” she writes, “I am telling of the instants that drip and are thick with blood.” A Breath of Life is structured as a dialogue between the “Author” and his character “Angela.” The name is significant: the Author fears that Angela, like Lucifer, will outdo her creator. In their agonic struggle, the author fluctuates between his love and hatred of Angela. Her orphic speculations on the meaning of her flickering existence become the Author’s inspiration, but they drive him so close to madness he considers killing her to save himself.

If this series was indeed envisioned as an improvement on the existing translations, one of the most significant corrections made was typographical: while the 1989 University of Minnesota edition of Água viva contracted the fragments that compose the novel into paragraphs, New Directions has restored the full line-breaks between them. These line breaks are essential to Lispector’s impressionistic style, as well as the narrator’s preoccupation with time. Stefan Tobler’s translation of Água viva also sheds the strictures of grammatically correct punctuation, a move that respects Lispector’s own creative use of sentence run-ons, fragments, and ellipses. He and Jonny Lorenz, who translated A Breath of Life, both manage to capture the subtle fluctuations in register and in the nuanced movement of Lispector’s late prose.

On the whole, Moser’s stable of translators does an admirable job with Lispector’s dizzying and self-referential prose. The three new translations are doubtless an improvement on their predecessors. Idra Novey’s translation of The Passion According to G.H. is the shakiest of the four, but in fairness to Novey, it is also the most difficult to translate and perhaps the most improved in comparison to its predecessor. Her translation snags when she insists on a literal plotting of Lispector’s syntax, sacrificing the poetics of the original Portuguese as well as a clarity that might be achieved by bisecting or reordering some of the author’s winding sentences. Brazilian Portuguese is surprisingly tolerant of run-on sentences, and remaining faithful to them in English sometimes means prose that reads rather sloppily. But these decisions may not be strictly Novey’s: Moser, who edited the translations, suggests in the preface to Água Viva that one of his editorial priorities was to respect Lispector’s mania of demanding that her translations be published without a single alteration in punctuation.

Lispector’s detractors—and they are few—mainly attack her for what they perceive as narcissistic pseudo-philosophy. But the adjectives often deployed against her—“hermetic,” “mystical,” “universalistic,” and even “philosophic”—sound to me like compliments. It is true that readers less fond of philosophical language games or existential speculations will not enjoy these novels. “All sudden understanding closely resembles an acute incomprehension,” G.H. intones portentously. “No,” she corrects herself. “All sudden understanding is finally the revelation of an acute incomprehension.” This is exactly the sort of existential grandstanding that has earned Lispector accusations of solipsism and inscrutability. But does anyone consult a high priestess for her humility?

Adam Morris is a San Francisco writer and translator. He is a recipient of the 2012 Susan Sontag Foundation Prize for literary translation.

2 thoughts on “The Brazilian Bird of Prey: Four New Translations of Clarice Lispector”