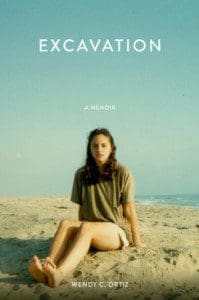

In her memoir, Excavation (Future Tense Books; 244 pages), Wendy Ortiz looks to her journal entries and memories to piece together a narrative of her adolescent traumas. In the 1980s and ‘90s, Ortiz was seduced by her 8th-grade English teacher who instigated a relationship that would last five years. Now a registered sex offender, “Jeff Ivers” (as he is called in the memoir) is described in both flattering and disturbing terms, Ortiz’s attraction to him having as much to do with his charisma as with the danger his love promises. Now married, and with a child of her own, Ortiz digs into her past so as to fight her demons, revealing with utter honesty and unrestrained prose the vicious details of her ordeal. But rather than point fingers or give a moralizing depiction of a taboo story, she instead shows us the intimate spaces and the blurred lines of the relationship—as seen by a girl who doesn’t fully believe herself to be the victim of an older man’s predation.

In her memoir, Excavation (Future Tense Books; 244 pages), Wendy Ortiz looks to her journal entries and memories to piece together a narrative of her adolescent traumas. In the 1980s and ‘90s, Ortiz was seduced by her 8th-grade English teacher who instigated a relationship that would last five years. Now a registered sex offender, “Jeff Ivers” (as he is called in the memoir) is described in both flattering and disturbing terms, Ortiz’s attraction to him having as much to do with his charisma as with the danger his love promises. Now married, and with a child of her own, Ortiz digs into her past so as to fight her demons, revealing with utter honesty and unrestrained prose the vicious details of her ordeal. But rather than point fingers or give a moralizing depiction of a taboo story, she instead shows us the intimate spaces and the blurred lines of the relationship—as seen by a girl who doesn’t fully believe herself to be the victim of an older man’s predation.

Excavation begins with the first day of the eighth grade, painting a picture of a girl whose conjured disaffection goes hand in hand with her teenage blasé attitude. The Wendy we meet already shows her acquaintance with danger, but we also see that she’s an ordinary thirteen-year-old child. When class begins, the man who steps into the room is a new teacher, 28-year-old Mr. Ivers. Unlike her other teachers, Mr. Ivers seems to understand these students, knows how to talk to them and get them to let down their guard. Soon, the kids are laughing, responding to his jokes, opening up to his charismatic personality.

Soon after class, Wendy reveals to Mr. Ivers that she’s writing a book, which she keeps in a plastic binder. “Mr. Ivers wants you to call him at home,” Wendy’s friend announces. “Here’s his phone number. So you guys can talk about your book.” At home, in the privacy of her room, masked by the din of her alcoholic parents’ blaring TV, Wendy obliges and gives him a call. They talk about movies, Wendy’s plans for college, music, books, the topics one might discuss with a good friend. But he is her teacher, and the power dynamics teeter strongly in favor of Mr. Ivers:

“Over an hour into this conversation, this conversation that forced me to listen, reply, and think swiftly to keep up with the speed and flow of it, he used the word ‘crush.’

He said ‘crush’ like I said it in sixth grade when I was talking about Marc Hendricks.

He said, ‘you’ like I was the embodiment of some kind of dangerous elixir threatening to seduce him, forcing any control he might have over himself underground.

My teacher was revealing to me, admitting to me, that he had a huge crush on me.”

As readers, we watch in horror as this first phone call devolves into something monstrously sexualized and tantalizing, and characteristic of the conversations that ensue in the following months and years.

After that first phone call, their interactions migrate into the public. They go bowling with a group from the 8th-grade class, and just out of sight of the other teachers, parents, and students, he sends her seductive glances, whispers in her ear, and makes inappropriate gestures and suggestions. Soon he is giving her rides home, and later, visiting her while her parents are out. He never masks his intentions, only tells her to promise never to write about their conversations in her journal, which she continues to do in secret through her teens. He seduces her, offering her the desirable idea of sex with an older, more experienced man, but always stopping just short of the actual act. Eventually, that barrier, too, is breached.

“With Mr. Ivers in my life now, I felt strangely outside of things, but the new places I found inside myself were suddenly starting to feel unpredictable, explosive, alive,” Ortiz writes. This feeling of being outside of things follows her into high school, where she behaves like a typical teen and dates boys her age, all while continuing her involvement with Mr. Ivers. Ortiz shows how her daily life—made up of her alcoholic mother, her teenage friends, marijuana binges, and beloved songs—is inextricably woven to Mr. Ivers. She matter-of-factly describes how his talk of his girlfriend and other women sickens her, makes her flare up with jealousy, and she reveals how deeply damaging this emotional manipulation was. For years, he beckons her back, and she never fails to answer his call.

Excavation mostly moves through time chronologically, but it occasionally takes us into the future —Ortiz’s college years, her life as an adult, teacher, and mother. These shifts help calibrate the perspective of the young Wendy with that of the adult Wendy, creating a multidimensional space for the narrative to lay and for the effects of her adolescent traumas to fully unfold. Ortiz masterfully blends fact with idea, never straying into melodrama or heavy-handedness. Her turmoil is presented simply as part of the natural rhythm and flow of her adolescence; she shows her everyday experience, and conversely, the underlying darkness of that fact.

And while much can be said about how wrong this relationship is—psychologically, morally, legally—Ortiz’s goal is not to cast blame on the perpetrator nor on herself. (Sometimes, aspects of their involvement—the familiar problems found in a relationship between peers; the bickering, the making up of an imperfect romance—might make the reader briefly forget that Mr. Ivers is an adult and Wendy a child.) She does not seek to moralize nor does she try to make excuses for either of them. The memoir is simply her story, raw and honest. (Ortiz even articulates her teen self’s moments of private thought, showing us a version of her life separate from the existence of her teacher.) The book’s success is in its candid representation of a story often left to newspapers and courtrooms to tell.

“My own composition changed when I was taught by this man,” Ortiz writes. “He seeped into my existence. I smelled the danger and for many reasons, I wandered in.” Fittingly ending the memoir with a scene at the La Brea Tar Pits, which trapped and fossilized the unfortunate prehistoric creatures who wandered into them, Ortiz speaks of her personal excavation as a perpetual journey, a necessary exploration of a hidden story. While personal, her memoir is also universal in its undertaking of that discovery of hidden pains and truths, of attempting to move forward by first returning to the unexplored past. Ortiz’s story sifts through dark, difficult matter, and surprises and enlightens us with complex truths we often feel more comfortable leaving unexamined.