Value is everything. You can tell a lot about a society by what it values. In America, things that move tenaciously with the bravura of a cha-ching—like buildings, prescription pills, and personal data—are big business, practically a national pastime. But what about the arts? The arts are trickier. Art is messy, it’s too human, and by virtue of provoking thought and reflection, too ambiguous (although the market for fine art makes capital use of ambiguity). How do you judge art? What’s it worth? What does it mean? Where’s it from? Who cares?

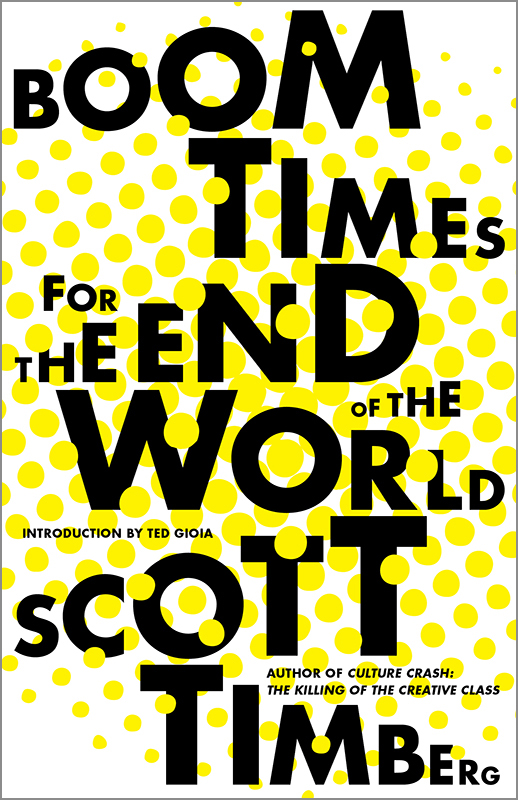

Scott Timberg, former arts reporter for the Los Angeles Times and all-around cultural evangelist, cared. A lot. And he wrote two books to try to convince us we should too, before it’s too late. Boom Times for the End of the World (Heyday, 304 pages) is Timberg’s posthumous collection of essays and reflections from the last two decades, written with verve, curiosity, and refreshing sincerity before the cruelties of circumstance cut his life short. Timberg’s most potent writing posed a simple question: Where do the arts—and the cultural ecology that sustain them—fit in a dopamine society that values money and winning above all else?

Timberg was born in Palo Alto in 1969. Raised mostly in Maryland, he went to Wesleyan University, got a master’s in journalism from the University of North Carolina, and moved to Los Angeles in the 1990s to work for the alternative press New Times LA. Music critic and close friend Ted Gioia, who wrote the new volume’s introduction, claims to have never met anyone who loved journalism more than Timberg: “For him, the newspaper business was more than a vocation, it was almost his destiny.” From there his twin passions, Los Angeles and the “culture business”—the large chain of people that extended from successful artists to newspaper reporters like Timberg all the way to the minimum-wage film buff who worked at the local video store—propelled him forward. When he accepted a full-time post as arts reporter at the Los Angeles Times in 2002, it was nothing less than fate, an opportunity to absorb and report on the cultural life of his great “misread city.”

Much of Boom Times reads like a time capsule from another world. The opening fifteen pieces—over half the book—come from Timberg’s first decade of reporting, just before things went bust in 2008. It’s an eerie feeling to revisit the near past, when Spike Jonze was still the mysterious new kid on the block, when coolly intellectual Christopher Nolan was still pondering his next move, when William Perreira’s LACMA still existed. Starting with a profile of photographer William Claxton, the man who “created the visual reality of West Coast jazz,” Timberg offers us lucid glimpses at a host of SoCal cultural figures including novelist John Rechy (“narcissism, like Los Angeles, is one of Rechy’s great causes”), publisher Benedikt Taschen (“the Hefner of the art book”), and comic book writer Adrian Tomine (“Tomine, like a songwriter, works in miniature”).

These profiles succeed in evoking a sense of indispensability. While a few skirt the line of puff, they flesh out their subject’s importance without denuding them of their mystery. Timberg had a knack for scoring choice quotes, helping to build portraits filled with immediacy. Both the range of takes and the quality therein speak to the impression Timberg must have made on both his subjects and his sources, a passionate conversationalist for whom people—everyone from stratospheric Steven Soderbergh to reserved Richard Rodriguez—wanted to talk to. Whether or not you knew about them, Timberg made it clear his subjects were worthy of attention.

As the first decade of the new century approached the second, however, strange rumblings began to grow louder, and his senses attuned to more seismic observations. In the book’s eponymous essay, which picks up a train of thought Mike Davis explored a decade earlier in his seminal Ecology of Fear, Timberg asked: “What does it mean that the dream life of the richest, most scientifically advanced nation in history is troubled by nightmares of the end?” By looking at three recent works—Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and Matthew Sharpe’s Jamestown—to try to understand why “literary novels with end-of-the-world settings” were surging in popularity, Timberg found that the fallout of 9/11 had settled upon the culture at large like a fine ash of disquiet. The war that followed the terrorist attacks catalyzed American political engagement on a level not seen since Vietnam. It was becoming evident that the new century was not quite lining up as its champions in politics and economics had boasted. Presciently, one novelist suggested, “You’re going to see more of this.” But with a cruel dose of irony, “Boom Times for the End of the World” forewarned what was yet to come. With a dateline of March 25, 2007, a new event loomed closer like a mean storm on the horizon.

Between 2008 and 2009, over four million Americans lost their homes during the largest economic downtown since the Great Depression. Whole global industries shuddered and the devastation that followed the sweeping tidal wave from Wall Street to Main Street and on across the oceans would have palpable impacts on nearly every rung of society. Meanwhile, with the immaterial internet on the ascendancy reshaping our relationship to and engagement with art and media, the “culture business” took a double blow.

The Great Recession of 2007-2009 is the defining event of Timberg’s life. Ownership of the Los Angeles Times changed hands, bankruptcy ensued, layoffs were swift and penetrating. Timberg was not spared. The loss of the Times post is, according to Gioia, a loss from which Timberg never fully recovered. But while he was blindsided, he certainly wasn’t about to give up the fight, and it’s at this point—the post-2008 pieces—that Boom Times really opens up. Timberg spent the early part of the new decade researching and writing what became Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class, his examination of the effects of the tech boom and the Great Recession on the role of art in society and the culture industry as a whole. The New Yorker’s Richard Brody considered the book “a quietly radical rethinking of the very nature of art in modern life.”

In his quietly radical way, Timberg weathered the loss of his job, his home, and eventually his ability to stay in the city he loved by coming back with new, insightful pieces to evince the claim that something irrevocable was happening, that the sweeping changes of the neoliberal era were clearly having deleterious effects on the fabric of society. A number of pieces included in Boom Times (e.g. “Can Unions Save the Creative Class,” “How the Village Voice and Other Alt-Weeklies Lost Their Voice,” “The Revenge of Monoculture”) emphasized from different angles a sort of middle road, brick-and-mortar solidarity. Timberg argued that “economic trends favoring wealth consolidation and corporate mergers were an imminent threat to the ‘mid-list’ artist—the kind of person who does not enjoy widespread fame but nevertheless acts as a stabilizing and uplifting force in local life.” Emphasis on local.

Following the collapse of the housing market, hundreds of thousands of single-family homes and mom-and-pop storefronts around Los Angeles became the property of giant companies, squeezing renters for increasing drops of revenue and putting middle-class stability further out of reach. Whole communities were flipped upside down. The casualties included countless used bookstores, video stores, affordable family-owned cafés and eateries, a web of well-worn, interconnected small businesses and their people that populated what Timberg referred to as the cultural ecology of an urban center. (For an intimate look at these impacts, see Timberg’s Times deskmate Lynell George’s After/Image: Los Angeles Outside the Frame, Angel City Press, 2018.)

As Boom Times progresses, the pieces get more probing and urgent. In “Can Unions Save the Creative Class,” Timberg explores the history of guilds and unions in the creative world—going back centuries—and the thorny complex at the heart of creative artists’ sense of identity. From the Renaissance-era “genius” to the Victorian bohemian, artists’ tendency toward self-deception mixed with ever-unstable economic landscapes have fueled a long history of resisting collectivization. As for contemporary society, Reagan-era bootstrap individualism and yuppie professionalism moved college-educated creative workers away from considering themselves union people; add to that the mainstream Democratic Party’s eventual abandonment of the working class in favor of the slicker “professional class.” With the fracturing of urban centers as organs of heterogeneity and collective action thanks to a “half-century of suburbanization and several decades of the internet,” as Timberg pointed out, unions have less and less opportunity to find purchase.

In “How the Village Voice and Other Alt-Weeklies Lost Their Voice,” Timberg looks at the life and death of alternative newspapers as a cultural force, a world he cut his teeth in. “The alternative press comes at a very specific point in American history,” Timberg quotes film critic Manolha Dargis as saying, “and its demise does too,” one she suggested had less to do with technology than a show that had run its course. Ultimately, technology has played an integral role in reshaping our notions of value, of participation and nonconformism, and the way we access and interact with information. The fact that Al Jazeera America published the piece, rather than any of the recognized outlets Timberg had worked with, adds a sort of coup de grâce.

In “Down We Go Together,” an excerpt from Culture Crash, Timberg decries the way economics and technology have synthesized to “undermine the way culture has been created… crippling the economic prospect of not only artists but also the many people who supported and spread their work, and nothing yet has taken its place.” Timberg’s detractors have pointed to his overemphasis on gloom without solutions. But standing in the way of anything practicable might just be America’s obsession with celebrity and its suspicion of art. Others point to the power of the internet to disseminate culture instantly and without gatekeeping. But Timberg didn’t find such arguments convincing. “Much of the writing about the new economy of the 21st century, and the internet in particular, has had a tone somewhere between cheerleading and utopian,” he wrote elsewhere in the same piece. For working creatives, the reality of the 21st century reshuffle is, more often than not, something along the stark lines offered by former New Times LA editor Joe Donnelly: “What artists do now is help brands build an identity. That’s where we’re at now.”

If that sounds gloomy, that’s because it is—and Timberg was writing before the coronavirus pandemic. We’re not talking about access and outlets, we’re talking about viable livelihoods. The pandemic also revealed that the initial wave of fleeing urbanites would not have as profound an impact on lowering rents as initially forecasted, thanks largely to that corporate land grab a decade earlier. “History shows that capitalism tends toward monopoly unless some counterforce pushes back,” Timberg wrote in “The Revenge of Monoculture.”

Much of Timberg’s work is deeply prescient. Despite the eager tone, Boom Times for the End of the World also reads a bit like a horror story, especially given what we know now: that Timberg ended his own life in December 2019, a mere two months before the start of what became the latest blunt force trauma to the creative class. At its most vulnerable, Timberg’s collection feels like a journal from a society’s last days, dispatches from some distant outpost right up until the signal went dead. I think of the romantic quality to his piece about a trip to Joshua Tree with his wife and toddler a mere decade before the area became a battleground between locals and developers, a place so ridden with Airbnbs the string lights in their backyards blot out the stars.

Apathy and paranoia have stalked every step of modernity. But while “all writers are at some point briefly under the impression they are in the forefront of disintegration and chaos,” as Martin Amis suggested, Timberg’s work in Boom Times rarely indulges the despair. His dedication to art’s role in society never wavers, as in his piece on Gustavo Dudamel of the LA Philharmonic, which closes the book. Written months before his death, it is as bright and dogged as the opening essay from two decades prior.

What is the value of art? Books like Boom Times for the End of the World encourage us to ask ourselves this very question. Two decades of being fed instant gratification (and outrage) has dulled our imaginations and tampered with our patience to feel without the compulsion to click or swipe. The pervasive atmosphere of a blockbuster culture that venerates hollow celebrity and heartless materialism continues to corrode our awareness of the role we play in the forces of history and the sense of solidarity integral to a healthy society. “The price we ultimately pay,” Timberg suggests, “is in the decline of art itself, diminishing understanding of ourselves, one another, and the eternal human spirit.” The stakes are high. Value is everything.

Marius Sosnowski is the managing editor of Dispatches, a California literary arts and culture magazine.