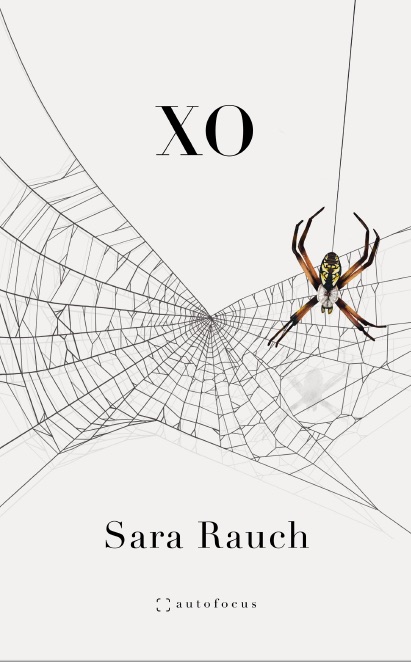

Most readers (all?) live for the books that compel them to ignore worldly distractions in order to reach the final page with as little delay as possible. I had that experience recently when I read Sara Rauch’s new memoir, XO (172 pages; Autofocus Books), which chronicles the author’s inexorable trajectory from a monogamous relationship with a female partner to a dizzying, disorienting affair with a heterosexual man whom she met as a student at her West Coast MFA program. He was an established, much-published writer. He was also married and one of the program’s faculty.

Years ago, I read a Harper’s article in which the writer offered the theory that affairs are the most exciting events in more than a few people’s lives. Those of us in the grip of a love affair often describe ourselves as “swept away,” “powerless to resist,” “driven mad by passion”—each an apt paraphrase of the French proverb “Le coeur a ses raisons que raison ne connaît point” (“The heart has reasons that reason doesn’t know.”) When the affair ends—if it ends, although most do, it seems—there is sometimes carnage, a broken home, disappointment, regret.

But on the other side, there is also on occasion clarity and forgiveness. Perhaps the forces that compel people to have affairs are as much about the need for a reminder that life can transcend the routines that often define it as it is about a desire for romantic attention.

Whatever compels us to enter into one, the love affair provides the subject matter for more than a few memorable films and television shows. (In the mid-’90s, I saw The English Patient six times in the theater—I still wonder what possessed me, and think almost as often now of the well-known Seinfeld episode that made hilarious and merciless fun of its fans as I do of the film itself. Seinfeld critique notwithstanding, Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of Michael Ondaatje’s sublime novel was irresistible to my twentysomething self.)

Affairs have also been the subject of well-regarded memoirs such as Gina Frangello’s Blow Your House Down, Ann Pearlman’s Infidelity, and Wendy Plump’s Vow, along with the classic novels Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, and The Good Soldier. Readers are at once riveted and scandalized, swooning and prone to moralizing when confronted with illicit lovers and their sometimes-frantic, guilt-ridden, thrilling maneuvers.

With XO, Rauch has written an engaging and eloquently contemplative account of the affair that several years ago tore through her life like a hurricane, leaving little intact after its winds and torrential rains had receded.

I had the opportunity to interview Sara Rauch about XO via email and Google Docs.

ZYZZYVA: Throughout XO, you write eloquently about love, sexual identity, religion and faith, and bears (!), among other topics. Figures as diverse as Simone Weil and Ani DiFranco also make appearances, which results in a book I think it’s fair to describe as a braided narrative. Please comment on this structure. Was it there from the earliest drafts?

Sara Rauch: Yes, I agree—this is definitely a braided structure, maybe one of those complicated fishtail French braids! There are many threads that I’m weaving here around the main one of my long-term relationship with a woman, the affair I had with a married man, and the resulting heartbreak, because I wanted the overall narrative to be bigger and more outward-looking than the traditional affair narrative. Affairs are usually quite insular, for a number of reasons, and mine was no different—that is, until it ended and I started thinking about all the ways it was woven into the fabric of my life, and also woven into the world around me.

In my earliest plans, I envisioned XO as a series of interconnected essays: there were some overlaps I knew would happen in the narratives, but as I started writing the book, I started to see that what I’d imagined as overlaps—or narrative “leaps”—were actually threads tying together a longer narrative. At that point, I abandoned the non-linear, multiple essay structure I had imagined and moved into a more traditional linear arc, though one with plenty of narrative explorations, side trips, and looks around—those smaller threads are meant to create a web, or braid, of connection which allows the story to transcend the merely personal and embrace spiritual, cultural, social, and cosmic possibilities.

Z: XO somehow manages to be both confessional and discreet, i.e. you disclose details about the affair that resides at the center of this book, but also keep many others out of view. Aside from what I imagine was a desire to protect the identities of the two other principals in this story, how did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

SR: This is a great question. Partly it was intuition and a writer’s eye toward what would make an interesting and propulsive narrative. I tend toward minimalism in all of my writing, and am often thinking about what I can get away with not revealing, even in my fiction; so I was working with the same ethos here, though heightened by the necessity to a) conceal from view what might be too telling about the principal actors and b) to honor my own need for secrecy. It seems strange to say, given how naked this book is, that I’m a very private person and I didn’t necessarily want to reveal everything here. So, I asked myself often as I wrote, what was important for the reader to know to inhabit the story, and what could be left to the folds of memory? I also approached the three parts of the book somewhat differently, when deciding what to include: for Parts One and Three, I had a lot more material to work with and fewer secrets to keep, so the work there became more about shining light on the necessary parts and letting the rest remain in the background.

For Part Two, there was a different kind of balancing act: I had to work entirely from memory (I’ve been blessed, or maybe cursed, with a very good one), and it’s a memory, a secret-no-longer-secret, that I’m still protective of, for a number of reasons—I wanted to show enough of the connection to make a reader understand why I might make the decisions I did, but I also wanted the reader to feel how important the secrecy was, and is, to that relationship.

Z: The focal events of XO occurred a number of years ago–what was the spark that led you to begin writing it? Were you thinking about how to process these events for a while before you started it or have you been working on XO for several years?

SR: Well, I was thinking about writing XO for a long time—in fact, the earliest piece I wrote about the affair, parts of which ended up in the book, was published in 2015, less than a year after my partner left me and the affair ended. But, the inciting incident, as it were, for XO in its book form, was my eldest cat dying in June 2020. Shortly after his death, I got sober, and I deleted my social media accounts. At that point, the first draft of the book fairly flew out of me. (I did some hefty revisions between the first full draft and the final book, but the body of the book was there right away.) I think I’d done much of the groundwork in my head over the years, and although anytime I write anything quickly, it feels somewhat miraculous, the truth is, I’d been moving toward it for a long time.

Z: Your first book, What Shines from It, is a short story collection. As someone who primarily writes fiction, I’m always interested in work by novelists and short story writers who write nonfiction, too. Do you prefer one over the other? And which of your fiction-writing skills did you find most valuable while you wrote XO?

SR: If I had to choose, one or the other of the two genres, I’ll always choose fiction. I can be more playful, less self-conscious, when I write fiction. But, for me, no matter what genre I’m writing in, a good story is a good story. The two skills I’ve developed as a fiction writer that I found most valuable in writing XO were finding the right structure early on, and then, getting the details right. I’ve always been keen on details, so I brought that careful eye with me to this book, and interestingly, I found that writing XO heightened what was already a natural instinct. Because I went into XO knowing that if I ever published it, it would be as nonfiction, I had to be faithful to the truth—even in the places where I compressed or stylized it—and I think this necessary constraint made the book better: it forced me to examine facets of the story at a revelatory level.

Z: What are some of the books and/or other art forms that most influenced your writing of XO?

SR: Probably the book that had the biggest impact on my writing XO is Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. That title, which I read during what I fondly call [in XO] “my time in the shed,” changed my understanding of how nonfiction could be written, and how to make art from heartbreak. XO was also profoundly influenced by Bon Iver’s eponymous second album and Ani DiFranco’s Educated Guess, both of which manage to be spare and lush at once, evocative and mysterious and raw: exactly how I wanted XO to feel.

Last but not least, though not technically an art form in the human sense of the word, spider webs became a sort of guiding image and symbol as I wrote the book: exemplifying the intricate, ephemeral beauty of creation and existence.

Z: Memoir is a popular form among readers, but I’ve heard more than a few writers say they think their lives are too uninteresting to write about. Another angle here is that memoirs are too revealing. I think often about something Francine Prose said about the form in regard to its potential to offend family and friends: “You have to decide if you want to write a good book or have a good Thanksgiving dinner.” What misgivings, if any, did you have to overcome while writing XO?

SR: Every time I sit down to write, I’m riddled with misgivings! For XO, those misgivings were less about whether or not the story I had to tell was interesting, and more along the lines of, Is this something I’m willing to publish? For a while, I wasn’t sure I would publish it, and I also seriously entertained the idea of publishing under a pseudonym. But in the end, I thought, You know, I didn’t go into writing because I wanted a polite, easy, well-mannered life. My family, at this point, accepts—or, at least, puts up with—my role as investigator and agitator. I wanted XO to be disruptive and honest and also expansive and inconclusive; I couldn’t achieve that by concealing from view the big issues I’ve spent my adult life grappling with—What is God? What is Love?—these questions are, to me, what makes being human interesting. To leave them out of this romantic narrative would have been disingenuous. That said, it did give me pause to write about God and Catholicism and how my spiritual life has evolved, even more so than it gave me pause to write about my sex life (what this says about me, I don’t know), perhaps because there’s no getting around the fact that I don’t have any answers, and I don’t expect I ever will.

Christine Sneed is the author most recently of The Virginity of Famous Men: Stories. Her fifth book, Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos, will be published in October, along with the short fiction anthology Love in the Time of Time’s Up (as editor). Her work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories, Ploughshares, the New York Times and many other publications. She lives in Pasadena, California.