“I wrote ‘Patriotism’ from the point of view of the young officer who could not help choosing suicide because he could not take part in the Ni Ni Roku Incident. This is neither a comedy nor a tragedy but simply a story of happiness…To choose the place where one dies is also the greatest joy in life.”

—Yukio Mishima, in a 1966 postscript to his short story, “Patriotism”

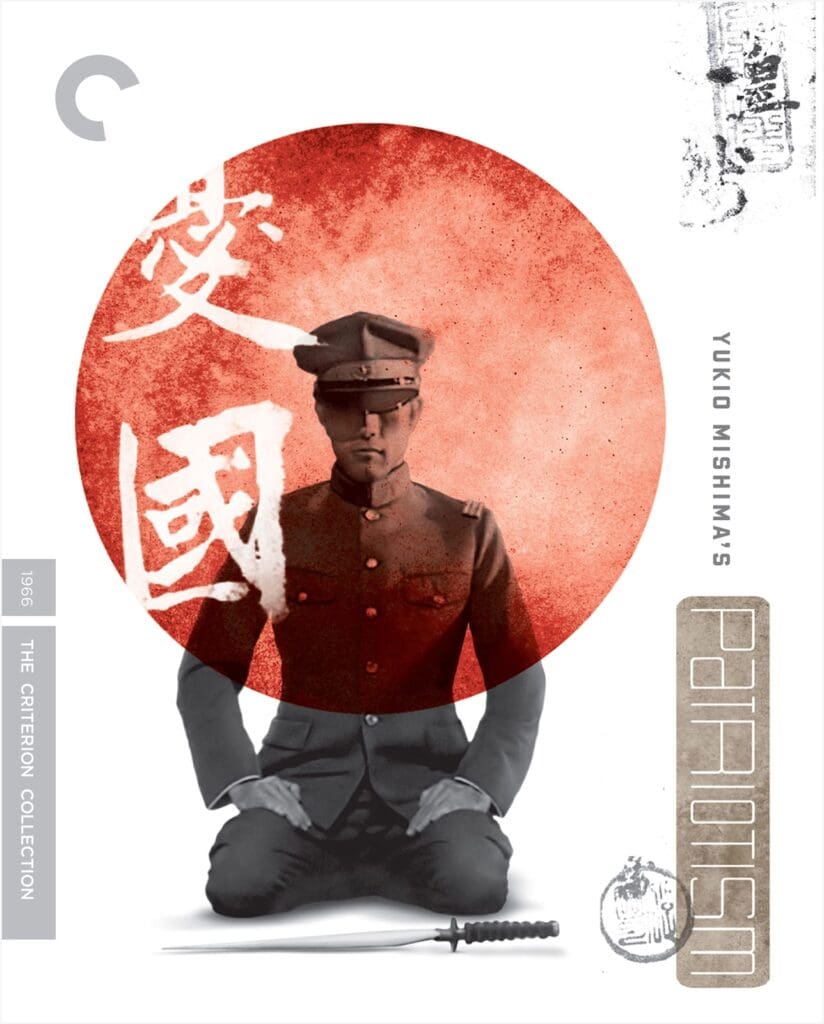

Army Lieutenant Shinji Takeyama sits on a Noh stage with his wife, Reiko (Yoshiko Tsuruoka). The only real ornamentation in the spare white room is an enormous kakemono banner, bearing the Chinese characters for “wholesome sincerity,” or “loyalty.” Takeyama wears his dress uniform, his eyes concealed behind the black patent leather visor of his peaked service cap (though occasional Svengali-esque closeups throughout reveal the depth of his fanaticism).

There is no dialogue in this story, only the crackling playback of a 78 r.p.m. recording of the “Liebestod” from Tristan and Isolde, Wagner’s soul-ripping “love-death” theme, the gold standard cliché of tragic romance. Plot information is conveyed by scrolling intertitles: Takeyama has supported the Ni Ni Roku Incident, a historic 1936 attempted coup by a group of young, pro-Emperor reactionaries who felt that the (already right-wing and militaristic) Japanese government lacked spiritual purity. Ordered to execute his co-conspirators, Takeyama and his wife decide instead to have sex and commit ritual suicide, a process which takes roughly twenty-seven minutes.

The sexual passion is quite buttoned-up; the lovemaking is almost entirely static poses designed to accentuate the muscles in Mishima’s—er, rather, Takeyama’s back (which are toned, in Mishima’s case, by eleven years of an obsessive workout regimen in pursuit of Greek-statuesque perfection). His hands fondle Reiko’s face and hair like a sculptor molding stubborn clay. That these erotic scenes lack an essential chemistry should come as no surprise to readers of Confessions of a Mask (1949), Mishima’s roman à clef about the agonies of the closet in Shōwa Japan. In that same novel, the protagonist’s first masturbatory experience occurs while gazing upon an image of the martyred Saint Sebastian, a sinewy male torso pierced by arrows—a tableau that certainly informs what comes next.

Now, Takeyama poses fetishistically in his military cap and fundoshi, a sort of iconic samurai jockstrap. Clutching his katana, he begins the ceremony of cleaning the blade. He dresses once more only to immediately undress his abdomen, to feel for the perfect, preordained spot in which to slide the blade. The positioning and insertion of the katana are as meticulous as if they were filmed for an instructional video. He thrusts and drags the blade into and across his belly with a steady hand, clenching his teeth as gore spurts onto his perfectly pressed pants (and as tears flow from the otherwise stone-faced Reiko). No hysterics are permitted here, only duty. Finally, with a handful of intestines, we get the money shot: Mishima’s mouth foams with spittle as he slices his own jugular, reaching an orgasmic climax among paroxysms of squirting blood. The floor, naturally, is white.

Reiko’s subsequent suicide feels like an afterthought, and features little of the gore and sexual anticipation of Takeyama’s death. It plays less like the double suicide of star-crossed lovers and more like Takeyama needed someone else to arrange his military cap just the way he wanted after he was dead.

Patriotism, based on Mishima’s short story of the same name, is something of a cinematic experiment. The audience and the author (Mishima adapted, produced, co-directed, and designed it) both seem to be Yukio Mishima. To him, it was a rehearsal for a sacred rite, an advance copy of a future autobiography. The sword was a prop. The blood was stage blood. But, as Mishima wrote, “art is a shadow.” “Stage blood is not enough.” On November 25, 1970, Mishima—by then, an international literary celebrity—would deliver his final performance. On that day, at the age of forty-five, he would hand off his final manuscript, stage his own pro-Emperor coup, address an assembly of troops, and commit seppuku. He did not honestly believe his coup would restore Imperial Japan; it was always doomed to fail, to end with the bloody exclamation point of self-annihilation.

Life was aesthetics to him; aesthetics were life. A meaningful, honorable, or glorious life could not exist without a beautiful death. At forty, one begins to decay and life after that is but a slow and cowardly death. Heaven must have been beautiful in the Bronze Age because men died before they were twenty. Now, it is a grotesque collection of ugly, pathetic, and aging bodies. Purity of resolve must be revered above all; waffling and fence-sitting must be stamped out. Mishima believed all of this, or claimed to.

His philosophy: you must pretend to be the man you want to be before you can become him. The performance becomes truth, if you believe it. If they believe it. And in 1966, Mishima was still peeking over his shoulder at the audience to see if they were convinced. Why else would he feel the need to rehearse? To so elaborately psych himself up for the deed?

Patriotism was not the last, nor even the first, time Mishima would perform his own death. In 1960, he was shot in the back and expired at length in Yasuzô Masumura’s yakuza film, Afraid to Die. In 1968, he portrayed a taxidermied human statue meant to embody “beauty cut down in its prime” in Kinji Fukasaku’s Black Lizard. In 1969, he committed seppuku in Hideo Gosha’s samurai film, Hitokiri. Throughout, Mishima continued to write like a man possessed, racing against death.

In January of 1966, Mishima brought the idea of a film version of “Patriotism” to Dai-ei Studios. Something else happened that January, on the 14th: Mishima turned forty-one. He had wavered and missed his self-imposed deadline for a beautiful death. Now there was a true urgency to his project. No one else could have played the role, at least not in the sense that Mishima needed.

For a contemporaneous book on the making of Patriotism, Mishima wrote, “Taking the stage in a role I had created would mean that, for the first time, I would be able to close a certain circle within myself.” His wide-ranging motives—vanity, self-promotion, impulse control, catharsis, self-destruction—could all be simultaneously valid if he so willed it. He searched for himself in a character, found what he wanted, and clung on to it long enough to close the circle—to make it an irreversible reality. Is Mishima’s story really one of “happiness?” Well, he said it was, and we can’t very well argue with him about it now, can we?

Sean Gill is a writer and filmmaker who won Michigan Quarterly Review‘s 2020 Lawrence Prize, Pleiades’ 2019 Gail B. Crump Prize, and The Cincinnati Review’s 2018 Robert and Adele Schiff Award. He has studied with Werner Herzog, video edited for Netflix’s Queer Eye, and was directed by Martin Scorsese (on HBO’s Vinyl). Other recent writing has been published in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Threepenny Review, and at Epiphany, where he writes the “Lurid Esoterica” column.