April 13. Almost midnight. Through the worn twill curtains, a viscous light was flowing into the apartment like amber. Park washed his face in the bathroom, took his meds, and sat down on the sofa with the remote. One click, and the blue light of the TV mingled with the sodium yellow of the room. He flipped through the channels. Game shows. Contestants competing for money, for marriage. The women are showing off, swiveling their hips and winking at the camera, and then they’re ranked by the amount of applause they receive. People awwing over tiny puppies. Slow, close-up shots of some new hybrid food, a rare delicacy. A man has to eat a glistening pile of meat and cheese until his face is streaming with sweat and an exhausted howl escapes from his mouth. Woops, applause, groans, laughter.

A pair of professors seated facing one another against a black backdrop. No audience, no clapping.

“There are generations of children who are growing up not knowing the meaning of the word ‘rain,’ ‘snow,’ ‘clouds,’ who have never seen the sea or the sunset in their lives. Are you saying that this is not a moral crisis?” said the pundit on the right side, a literature professor at Seoul National University.

“You are making a Romanticist error in conflating nature with morality. Nature in itself is neither good nor evil. Likewise, technology that is used to shape or control nature is neither inherently moral nor immoral. Less than two centuries ago, our ancestors argued over the morality of the ‘Iron Horse.’ Would you argue that the subway is evil because it bores through the earth and shuttles around humans in a sealed underground passageway?” said the pundit on the left side, a philosophy professor at Korea University. “Technology is strictly a matter of utility, not ethics.”

“I would be greatly presumptuous if I were single-handedly conflating nature and morality, as you put it. But take this for an example: You know that language shapes thoughts, ideas, and morals. Even you must acknowledge that in our Korean language, the word ‘God’ is literally, ‘Dear Sky.’ Long before I had ever romanticized nature, as you argue, our people have used words of nature to describe what is good and sacred, for five thousand years. When the people no longer know what a sky actually is—and many of the younger generations have never seen it—how would they have any consciousness of a God?”

“You have a false understanding of the nature of faith. God—at least in the Christian sense—defies representation or proof. If one needed the sky in order to recognize God, then that would not be genuine faith at all,” the philosophy professor said smugly, then carefully delivered the ultimate insult. “You speak out of sentimentality.”

“I’m not being sentimental. I’m being human,” his opponent replied calmly.

And on and on they went. Park turned off the TV.

“This is a nice place,” Park said. They were seated in the courtyard garden of an elegant restaurant in Gangnam, surrounded by trellises and arbors of roses, jasmine, and other dark and lush shrubs that Park didn’t recognize. The waiters in waistcoats flitted about discreetly like moths, lighting candles one by one.

“How many of these have you done?” Jina asked.

“What?”

“You know, mat sun.”

“Excuse me?”

“You are thirty-five and unmarried so you must have gone on at least two dozen.”

“What else do you know about me?”

“The matchmaker gave me the usual specs. Your height, your looks. You’re a senior engineer at the Department of Environmental Protection and you graduated from Seoul National University near the top of your class. But you don’t have much family money or the ability to finance a new apartment for us. You’re the only son of a widowed mother, which is guaranteed to scare off squeamish women. Physically, you have weak lungs, a common enough condition for those born before the Bio. However, I heard you have an IQ in the top 0.1%. So naturally, we may be a match.”

“You certainly speak your mind, don’t you.”

“Here’s what I think. I’m twenty-eight and the last of three daughters, so my parents are absolutely dying to get rid of me. My two older sisters both married at twenty-six although I’m much prettier and more intelligent than they are. My parents think it’s because of my personality. I don’t care much about shutting my mouth to flatter some man who is more stupid than I am. Do you care if I smoke?” She said, already reaching for her cigarette case.

“Be my guest.”

“I’m terribly bored by my parents’ endless entreaties and machinations. I’m just ready to end it all and marry whomever they think is appropriate. I’m tired. Do you know what I mean?”

“I think I do.” She smiled.

“You know, it’s funny. I feel like I can be honest with you. It’s not often that I feel that way at one of these things. The matchmaker did say we were an uncommonly good match with our astrological signs.”

“Western or traditional?” She raised an eyebrow.

“Why, traditional of course. Why would I put any trust in Western astrology for something as important as marriage? That stuff is just a bunch of nonsense.”

“They seem about equal in my esteem,” Park said.

She broke into a peal of silvery laughter. “I’m pleased that you disagree with me. At first I was worried that you’d be one of those scrawny, weak engineer types who don’t seem to have any opinions of their own. And please don’t take this the wrong way, but your first impression wasn’t too far from my expectation. But you know how to push back—I like that.” She took a long drag from her cigarette. “I feel like we’re going to get along quite well.”

Park wished he could come up with some sarcastic remark, but he couldn’t. As for himself, he did not yet know whether he liked or disliked Jina. She had a pale heart-shaped face and long, shiny hair falling half way down her back. She was wearing a silk sheath in canary yellow that complemented her ivory skin and jet-black hair. By focusing his eyes on her bare arms, he could almost smell the perfume on her wrists and elbows—floral and slightly musky. Yes, he supposed she was a beautiful woman. He just wasn’t sure if he could ever have any feelings for her. “You look very nice,” Park said, at last. Jina’s eyes started dancing; she was used to compliments and had been on the verge of impatience with him.

“Nice?” she purred.

“Your dress. It looks beautiful.” Park rambled a bit in his embarrassment.

“Oh yes, I suppose. It’s yellow so I figured I’d wear it. I see you’re not wearing anything for Yellow Day. You don’t have a tie or something?”

Park didn’t have a yellow tie or socks or anything like that. All day at work, colleagues had teased him about not being in spirit. “Being a spoilsport, Manager Park? Surely you don’t want bad luck in the next year?” One of the men, a junior engineer, even jokingly offered to trade a sock with him, so they can each have one that is yellow. But grateful though he was for their good-natured banter, Park was secretly glad about not participating in the whole thing.

“I don’t really believe in that stuff,” Park said.

“Goodness, you don’t believe in anything. Not astrology, not Yellow Day…” Jina smiled. “Is there anything you do believe in?”

Indeed, what did he believe in? He did not know. He was only ever sure about what he couldn’t believe in.

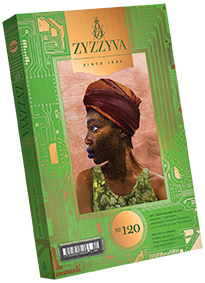

Juhea Kim was born in In Cheon, Korea, and moved to Portland, Oregon, at age nine. She graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Art and Archaeology and a certificate in French. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Granta, Slice, Catapult, Times Literary Supplement, Joyland, and many more. Read her story “Biodome” in its entirety in Issue 120 of ZYZZYVA.