Why?

Simple self-promotion? For fun?

Sheer ego? “Because no one else can?”

To wrest back the measure of control which a solitary typist enjoys?

Is it fear of living merely a life of the mind? The need to act out a fantasy?

Or is it a public therapy, an exorcism of demons?

Typically an author’s on-screen role in an adaptation is that of a background artist: blink and you’ll miss Kurt Vonnegut (a pedestrian in Mother Night), Amy Tan (a house partier in The Joy Luck Club), Chuck Palahniuk (an airline passenger in Choke), or John le Carré (a Christmas party-goer in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). Sometimes they are afforded an action that may be wryly humorous to the cognizant audience member: Margaret Atwood (as an Aunt) slaps Offred in the pilot episode of The Handmaid’s Tale. S.E. Hinton plays a nurse jostled by gang members in The Outsiders. John Irving nimbly referees a wrestling match in The World According to Garp. Denis Johnson appears as an ER patient (with a knife sticking through his eye) in Jesus’ Son. But every so often there comes along a larger role, one that’s more meaningful, elemental, or mythic.

Many writers are reluctant to claim center stage, retreating regularly to their secluded New England homes/Baltimore dive bars/peafowl farms/undisclosed locations, and surfacing in public life when contractually obligated. The outgoing, spotlight-seeking authors you’d expect have rarely appeared in films based on their writing: Ernest Hemingway never played The Old Man and the Sea, Bret Easton Ellis never took a stab at Patrick Bateman, Ayn Rand never oversaw an Objectivist Utopia, and, while F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald entertained playing their alter-egos in a This Side of Paradise adaptation, it never came to fruition.

Even among the greatest showboats and enfants terribles, such self-expression is infrequent. Outsize personalities like Charles Bukowski (a bar patron in Barfly) and Hunter S. Thompson (quietly smoking at a table in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas) appear in muted cameos. James Ellroy, happy to play a gratingly exaggerated noir character at readings and in interviews, sleepwalks through the (short film) adaptation of Killer on the Road, murmuring two words of dialogue and generally taking cover behind the other actors.

Norman Mailer’s self-directed roles (Wild 90, Beyond the Law, and Maidstone) belong more to his late ’60s bleeding-edge filmmaker’s identity, largely improvised and far removed from his prose. Martin Amis’ only screen appearance was as a child actor in A High Wind to Jamaica. Truman Capote may have hammed it up in Neil Simon’s Murder by Death, but when it came to his own material, he offered only reverential narration (A Christmas Memory, The Thanksgiving Visitor).

The following review is by no means comprehensive: I do not explore James Dickey’s unsettling turn as a Georgia sheriff in Deliverance, Gore Vidal’s assortment of walk-ons, or William Burroughs’ avant-garde experiments. The six performances I am most interested in involve true characterization: authors who are exploring, in varying degrees, a character they created in print. We see each of them come to terms with their literary fame on this unfamiliar visual terrain, all of their vanities and insecurities projected inescapably upon a screen, thirty feet high. Each role possesses a quality that might only have been expressed by their originator, and each grapples with an idea—or, more likely, an obsession, addiction, or destructive urge—which is fundamental to my understanding of their body of work.

1982

Stephen King is “Jordy Verrill”

“People like me really do irritate people like them, you know. In effect, they’re saying, ‘What right do you have to entertain people? This is a serious world with a lot of serious problems. Let’s sit around and pick scabs; that’s art.’…The Time critic should have addressed his complaint to Henry James, who observed eighty years ago that ‘a good ghost story must be connected at a hundred different points with the common objects of life.'”

—Stephen King, interviewed by Playboy in June 1983

The farmer Jordy Verrill hunches—wide-eyed, spellbound, and literally slack-jawed—as a meteorite plummets from the night sky into his pasture. Dressed in stained overalls and faded flannel, he rushes to the crater and can’t help but immediately touch the dangerous-looking, glowing extraterrestrial boulder. He yelps in pain—it’s hot!—and sucks on burnt fingertips. He widens his eyes to a size L’il Abner might call cartoonish, exaggerates his brow to an almost Neanderthal prominence, and begins soliloquizing with the “dern tootin” patois of a whistle stop (“You done it now, Jordy Verrill––you nunkhead!”).

Though he and his land have now been infected with an unstoppable, consumptive form of alien vegetation, he fantasizes throughout of a “fancy college” with a Department of Meteors, headed by a sneering professor (Bingo O’Malley) with a lockbox of cash who—maybe, just maybe—will pay enough for the space rock to settle Jordy’s debts and lend his farm legitimacy.

Far from being proactive in this pursuit, Jordy sits around drinking Ripple (a low-end, fortified “hobo wine”), watching Big Time Wrestling, listening to televangelists, imagining the disappointments of his dead father (also Bingo O’Malley), and making harebrained mistakes (like watering a plant in the hopes of reducing its growth). Meanwhile, he and his property slowly and completely succumb to the ravenous flora, until, twisted into a half-grass/half-man monstrosity, Jordy summons the will to commit suicide by shotgun. It’s implied that the entire world will soon share his fate. While King, at George A. Romero’s direction, plays the role “as broad as a freeway,” a genuine melancholy weighs on the proceedings as they march to their inevitable and gruesome conclusion.

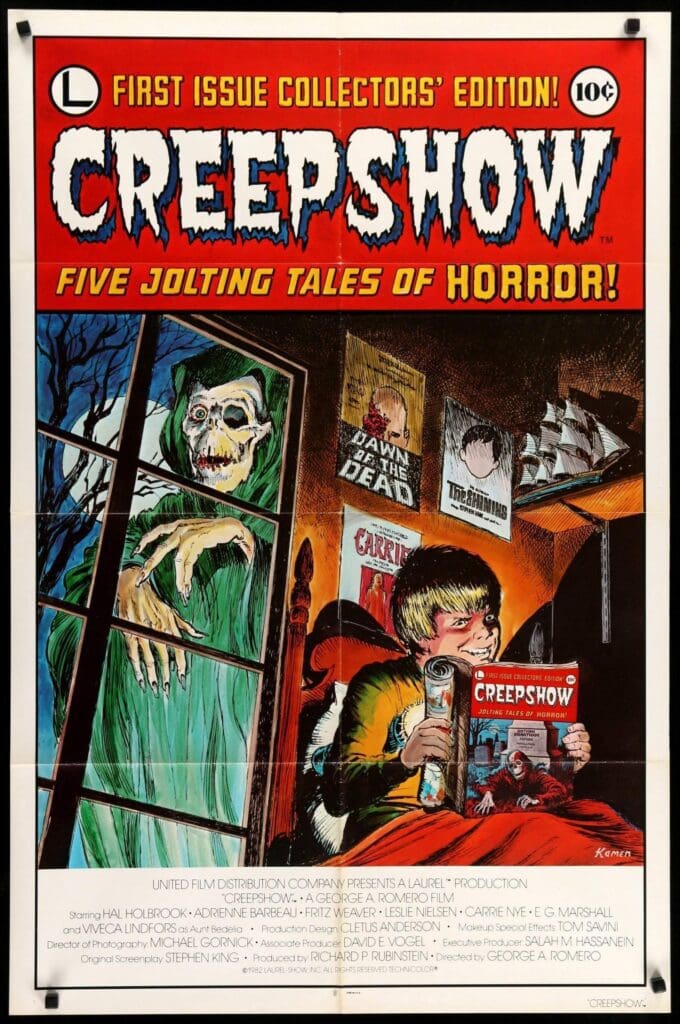

The original Stephen King short story “Weeds” first appeared in the May 1976 issue of the men’s magazine Cavalier (which, for context, featured a half-naked, pearl-strewn woman on the cover alongside the slogan “Alone in bed? Try Cavalier‘s magic potion of hot tales and spicy ‘tails’ to shoot you right off your mattress!”). Its adaptation, “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill,” is one of six segments in the King-penned, Romero-directed omnibus horror film Creepshow, an ode to the morbid, juvenile, and O. Henry-scented world of EC Comics (Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Shock SuspenStories). The film itself, visually and tonally, attempts to recreate the experience of a child reading a forbidden comic book after dark, hiding beneath the covers with a flashlight, fantasizing about mail-order voodoo dolls, X-ray glasses, and ghosts-trapped-in-a-can.

While taking the inspiration for its title from a Bob Dylan song (“The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carrol”), plotwise, “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill” is an obvious pastiche of the popular H.P. Lovecraft story “The Colour Out of Space,” one of the earliest and most lasting influences on King’s work. (When King’s father abandoned him at age two, one of the few items he left behind was an anthology of Lovecraft stories). It seems significant that King chose this particular material for his first and only starring role, in what is, essentially, a one-man show.

Its country superstitions and pastoral setting connect to his real-life uncle Clayton, a ghost story-teller, yarn spinner, alleged water witch, and major figure in King’s childhood. The folksy rural/blue-collar Maine charm recalls his early adulthood, where he and his wife made ends meet with mind-numbing work at industrial laundries, donut shops, and filling stations. (This latter representation may even show King bristling at critical perceptions of his overnight success and accusations of a nouveau riche lifestyle.) Then there’s the matter of the draining, all-consuming vegetation that ultimately destroys Jordy: in retrospect, it bears a resemblance to King’s battles with alcoholism and drug addiction that swallowed up his early 1980s, when the composition of entire novels were barely remembered (Cujo, for one) due to his cocaine habit.

Meanwhile, columnists from publications like Time and The Village Voice had recently deemed him “unoriginal,” “dismissible,” and “post-literate,” with the Voice depicting him, in caricature, as a bearded monster lording over sacks of money. The very tag-line of Creepshow (“The most fun you’ll ever have being scared!”) jabs at those whom King believes equate suffering and “scab-picking” with artistic merit. It’s easy to imagine him jokingly embracing, on-screen, the local yokel they think he is, the creepy backwoods New England rube they want him to be, encountering a meteor (or perhaps a meteoric rise?) and imploding beneath the pressure of forces he cannot understand, all while grasping for consideration from a particularly mocking wing of academia. It’s a parody of how King felt he was perceived by the literary world (and by artists like Stanley Kubrick, who were dismissive of his intellect), a burlesque for those who had never read one of his books, yet viewed him as a vulgarian bumpkin who wrote glorified campfire stories.

While his enduring success likely prevented such grievance-energy from calcifying into true resentment, King continued to grapple with these criticisms. After decades of celebrity, he took pride in debuting new work in literary venues like Ploughshares, Tin House, Virginia Quarterly Review, and The Paris Review (a long way from Cavalier), and found vindication in being awarded the National Medal of Arts from Barack Obama. In an interview with Stephen Colbert (taped the day after the ceremony while he was still wearing the Medal), King joked, “I couldn’t get any respect at all…when I published Carrie, the first book, I was like twenty-six years old, so a lot of the critics who dissed me back in those days are dead” (to which Colbert responded, “And how did they die, Stephen?”).

Maybe there’s a hidden warning in Jordy Verrill—from Stephen King to himself—about meteoric rises and gruesome downfalls, about relying on any single source for validation, about allowing ourselves to be crippled by opinion, about the ways we change when we’re exposed to something vast and intoxicating. Perhaps King’s warning is, though we may play the fool, and though there are cosmic forces beyond our control, we are never mere bystanders to our own self-destruction.

Sean Gill is a writer and filmmaker who won Michigan Quarterly Review‘s 2020 Lawrence Prize, Pleiades’ 2019 Gail B. Crump Prize, and The Cincinnati Review’s 2018 Robert and Adele Schiff Award. He has studied with Werner Herzog, video edited for Netflix’s Queer Eye, and was directed by Martin Scorsese (on HBO’s Vinyl). Other recent writing has been published in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Threepenny Review, and at Epiphany, where he writes the “Lurid Esoterica” column.