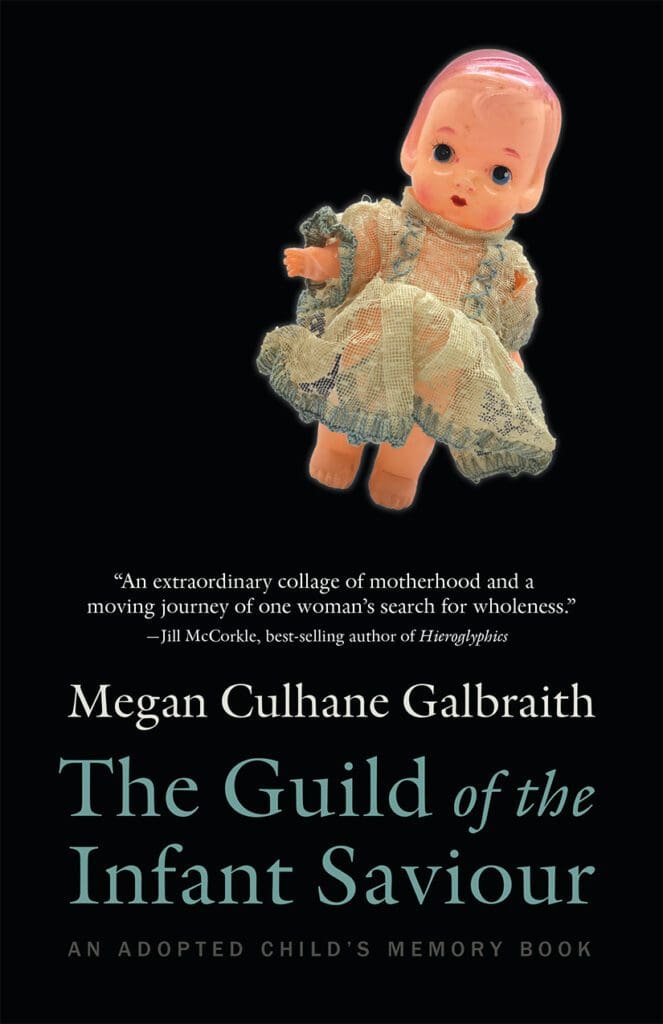

In Megan Culhane Galbraith’s hybrid memoir, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book (288 pages; Mad Creek Books), she investigates our desire for belonging with generosity and an eye for hidden truths. Galbraith was adopted as a baby in the late 1960s, and through a dual lens of subject and observer, she considers this tumultuous period of sexual freedoms for women and its consequences. The book’s unique form bridges the private and historical. Galbraith looks at programs for women and infants that echo an unconscious disregard; Catholic charities claimed to save unwed mothers, a domestic economy curriculum at Cornell borrowed orphaned babies so students could practice motherhood. Her photographs of domestic moments set in dollhouses appear alongside essays, prose poems, and collage.

Over email and a phone call on Mother’s Day—a day resonant with The Guild of the Infant Saviour’s quest and the anniversary of its acceptance for publication—we asked Galbraith about dollhouses, detective stories, and how she uses social history to contextualize gaps in her own past.

ZYZZYVA: The book’s narrative and photographs explore your personal experiences alongside investigation into adoption practices and family history. As the structure took shape, what was the relationship between the dolls, photographs, and writing? And why Memory Book?

Megan Culhane Galbraith: Adoptees have all been settled far away from our homes. I wanted to play with the idea of home and what better way to do that than in a dollhouse? The dolls became a window into my words. They allowed me an angle of removal, a third-person perspective that gave me space to then form questions I hadn’t thought about. Those questions then informed my essays. Art making is the way I tune into my child brain. As children all we know is how to play. As adults we can look back and ask, “Why?” There’s a saying that “children are innocent before they are corrupted by adults.” The photographs in this book represent both that innocence and corruption.

Interrogating my birth mother’s memory and mine is a central theme of the book. My baby book is actually called “An Adopted Child’s Memory Book,” so I began looking deeply at the pictures and asking myself what is it I remember.

Z: Can you speak to the intersections between looking into your memories and researching the history of adoption in New York, where you were born?

MCG: I’m a journalist by training. My birth mother would say “the past is the past; leave it there.” She had a past to leave behind. I had a past to find. When I couldn’t find specifics about my birth because many facts had been erased, I dug into the pasts of my adjacent biological relatives; they had a clearer paper trail. Dead ends and erasure are huge obstacles for adoptees, so I began to look in other places. I sensed the shame and piety in 19th century foundling practices that I imagined my birth mother felt in the 1960s. I understood my attachment issues thanks to the “practice babies” in the Domecon domestic education program at Cornell. My research buoyed and legitimized that I wasn’t alone in the feelings I was having about being adopted.

In exploring the idea of home, I wrote “Other Names for Home,” which is a prose poem curated from various foundling and orphan homes in New York City, where I was born. Its power derives from the baldness of those terrible names, which speak to how adoptees, orphans, and foundlings were objectified rather than humanized. One of the names was Home for Little Wanderers, as if the babies and children had just wandered off on their own accord.

Z: The Guild of the Infant Saviour was the Catholic home where your birth mother spent the last months of her pregnancy. As you say, the names are haunting. Did you find the detective-story aspect of tracing you and your birth mother’s past as having influenced the narrative, the tone, or other elements?

MCG: Adoptee lives are one long detective story with few clues and little truthful information. My narrative had to reflect that fragmentation, the silences and half-truths. The name of the place haunted me for so long. It was always going to be the title of this book. To me it implies a secret society, a Guild of people conspiring to hide women.

As an adoptee you have to turn over these stones in your life and you think, what’s under there, what am I missing? I wanted to take a prismatic look: I’m going to examine this form from all the angles and see what comes out. It was not something I could write as a linear narrative, as memoir. I tried, but the essay form is elastic, and the book is a collage. I’m relying on readers to see between the cracks. There’s a lot that resonates with the silences of the book as much as in what is said.

Z: In examining the missing pieces, you explore the influence of social constructions in women’s roles as daughters, mothers, wives. There’s a recovery of identity, and perhaps a claiming of time?

MCG: As writers we get to reassemble and bend time. There’s immense power in that, isn’t there? I mourn that I didn’t begin the process of finding my birth mother and digging into my past sooner, but we come to things when we come to them: Always on time, never ahead of ourselves. I wanted to honor that idea. Writing has a long shelf life. This book was written over the course of six years, with breaks in between when I put it in a drawer. By the time the reader reads any book, they’re reading about a life that happened years ago. This book is just one piece of me. It’s a slice of my past I wrote down, it transformed me, and I’m along the path to the next thing. All we’ve got is this moment, right? That’s why the last line of the book is important to me. It shows the precarious balance of living in our human bodies and how hard it is to stay present while feeling the future bearing down.