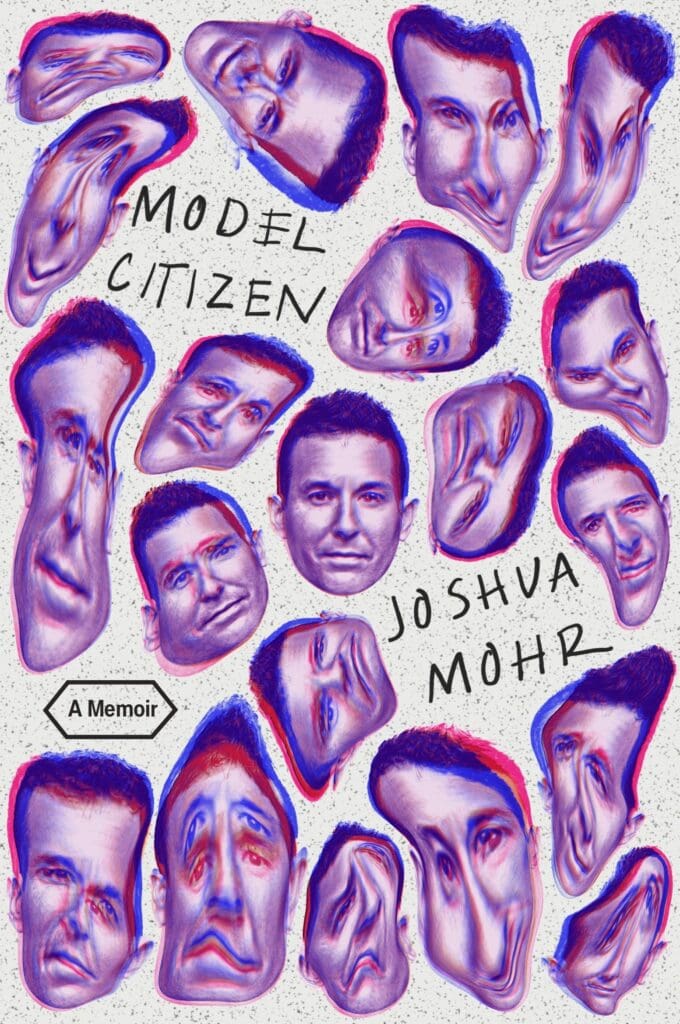

Model Citizen (336 pages; Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is Joshua Mohr’s memoir on addiction, sobriety, and fatherhood. It’s a brutally sincere addition to his repertoire that includes the previous memoir Sirens and five novels. Told in a series of non-chronological vignettes, Model Citizens begins with Mohr’s jagged path to recovery in episodes of self-destruction and regret. We’re pulled so viscerally into San Francisco bars where one drink turns into a blacked-out night that we feel like the gears in Mohr’s brain, trying to make sense of how we got here. We also experience the anguish of recovery and relapse, drawn to compassion at Mohr’s determination to do better.

The fast-paced narrative veers sharply when Mohr suffers from multiple strokes as a result of his long-term drug abuse. Here, the book expands with Mohr’s realization that he has too much to lose to die young. Forgiveness comes, but it is a journey involving his cherished daughter and unconditionally supportive spouse. Mohr dedicates this memoir “To those of us who want to do better,” and by the end of the memoir, we know why: this is the portrait of a former addict who has rebuilt the shame of his past through love and the act of writing.

Mohr, whose essay “San Francisco Loved Us Once” appeared in Issue 112, spoke to ZYZZYVA via email about San Francisco, the emotional reckoning of addiction, and his writing as a legacy to his daughter.

ZYZZYVA: You write about the San Francisco of old in such a way that it made me nostalgic and wistful for the way the city was before the pandemic. Who were some of your literary influences when writing about the city?

JOSHUA MOHR: As a writer, I always seek to aim high, though I’ll probably fall short of those esteemed water marks. So, for Model Citizen, I wanted San Francisco to be a character and attempted to channel authors I admire for their skills capturing place(s). Joan Didion’s Los Angeles, James Baldwin’s Manhattan. And of course, you can’t really think of San Francisco writers without mentioning Armistead Maupin and Richard Brautigan, who both talked about our town with so much heart and cerebral energy. If we do it right, setting has blood in its veins, just like a player.

Z: There are many moments where you address the reader in your writing: “What’s that one thing in your life that you wish to control, yet the compulsion spins constantly, relentlessly? We all have that seductive adversary, the voice in our head calling us to calamity. What’s yours?” You sometimes even give us advice. How did this second person narration help you write about addiction, relapse, and sobriety?

JM: I use these flights of direct address to invite the implied reader into the construction of the book. The best example is early in the narrative, in which I watch my young daughter tumble down the stairs. I render it in excruciating detail, and then after the scene is over, I alert the reader that I had been sitting on those exact stairs when I composed the scene on the page. I want her, the implied reader, complicit, close, feeling the book’s bad breath. That’s what visceral means to me, closing the audience’s proximity so she feels like we are building the book together.

Z: There are many scenes in the book that take place in the hospital, including drug overdoses and your surgery, and I sensed a lot of helplessness written into those passages. Could you talk more about your emotions during those scenes?

JM: It was such a marvelous mind-fuck! Especially once I had the surgery, and they said it was successful, and then only a couple years later, wham, I have another stroke. It was demoralizing, and your right about the audible helplessness in those hospital sequences. But there was another use, too: those feelings of powerlessness created a juxtaposition to my addict brain, which is also helpless to resist the tug of drugs. I wanted to put those potent forces in conversation with each other, dynamically pointing out connections, sure, but also the frictions, the dissonances, the confusions. In fact, I write into the confusion, into the moral mud in my work. I’m not interested in any pat, pre-packaged, or easily digestible answers. That’s not art to me.

Z: I was touched by the way you leave your writing as a legacy for your daughter; it makes your honesty and disclosure in Model Citizen even more resonant. You write: “This book is a plot of earth allowing her to work her dig, so she can form an understanding of me, of our life.” Given this self-appointed responsibility, what was it like to write yourself as a character in this memoir?

JM: It was so hard! It feels important to me to give her this warts-and-all access to my story. I never really knew my father. Sure, I knew his public codes and persona, but not who he actually was, and then he died so young. Of my very complicated life, that’s arguably the biggest tragedy—that he never trusted me with knowing him, truly knowing him. And so, I intentionally over-corrected: if I die young, too, and the reader(s) learn in the book that it’s a cogent possibility that I might not make it out of my forties, Ava has this unvarnished, no airbrushed account of her old man. For better or worse. At least, I got to write her a love letter on my way out.