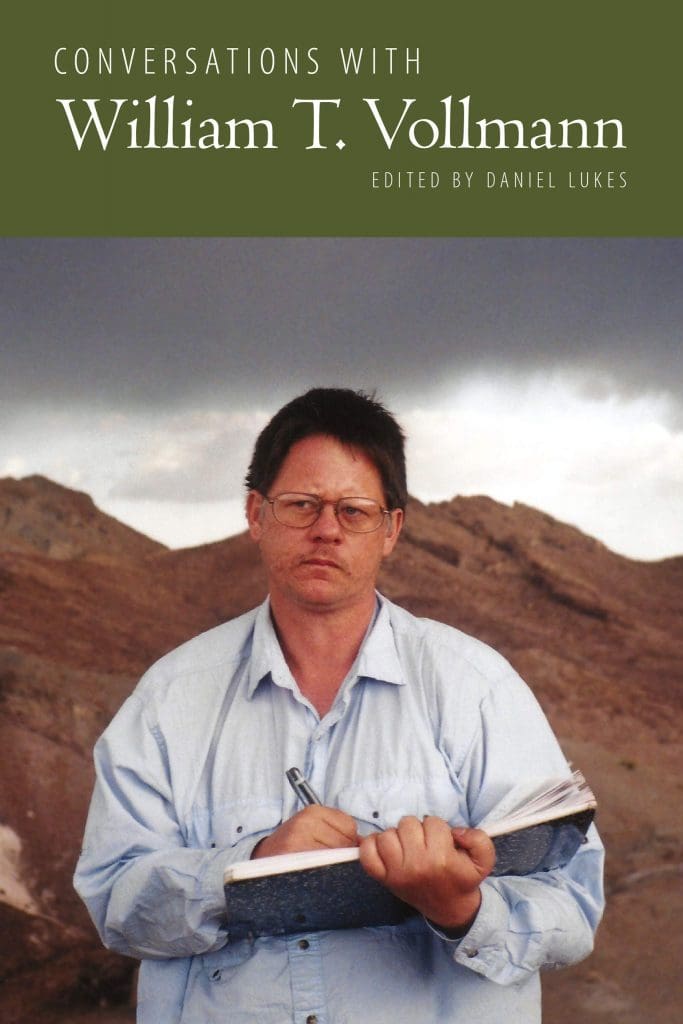

An interview is by definition a species of performance: by the subject, struggling for definition, or invasion; and by the interlocutor, finding his or her own path in a journalistic enterprise perilously akin to speed dating. Conversations with William T. Vollmann (252 pages; University of Mississippi Press), edited by Daniel Lukes as part of the publisher’s “Literary Conversations” series, fulfills both functions.

The incorrigibly ambitious Vollmann is the author of myriad explorations into Western mythologies, European history and literary journalistic inquiries into the roots of violence and environmental dystopia. His latest novel, The Lucky Star, returns to the Tenderloin underbelly he explored in Whores for Gloria, Butterfly Stories and The Royal Family.

As the “Conversations’’ volume documents (and I can attest through personal experience), Vollmann is an enormously entertaining subject (God knows how he finds the time to sit for the sessions) with a Tom Waits-like ability to assume a persona that may or may not resemble the “real’’ Vollmann. He remains a mystery man on offer in the book’s cagily revealing twenty-nine interviews. Someone so direct indisputably has something to hide, if only to protect what is needed for the act of creation.

Lukes inherited the project from the late Michael Hemmingson, the co-editor, with Larry McCaffery, of Expelled from Eden: A William T. Vollmann Reader, but started fresh, purposely excluding better-known interviews by Madison Smartt Bell and Tom Bissell for less widely known material.

Vollmann’s contrarian temperament is apparent in the first interview, by Jonathan Coe for The Guardian. When asked about his then nascent project Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes, he says:

“The first volume, The Ice-Shirt, will re-tell the story of the Norse landings in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. The second, Fathers and Crows, is about French Jesuits in Canada in the seventeenth century. The sixth (which is already well-advanced) will describe what happened when repeating rifles were introduced into the Arctic,” Coe writes. “You will realize by now we’re dealing with an extraordinary and ambitious writer, whose energy and commitment to his work seem boundless. I asked him whether he felt that other writers weren’t a little lazy by comparison.

“‘I think there’s too much easy writing, yes,’ he says gravely. ‘I see a lack of research and also a lack of balance. For instance, in a lot of narratives that are coming out now about Europeans and Indians, just as a hundred years ago such books would have portrayed the Indians as ignorant, bloodthirsty savages, now they’re quick to idealize the Indians and say that Europeans are all imperialists and exploiters. But it’s not that simple, and everyone deserves his chance to be portrayed as an individual as well as a member of a group. Everyone has some virtue as an individual.’”

In a 1992 session with Cary Tennis of the East Bay Monthly, he expands on his reportorial methods, whether talking with prostitutes or skinheads:

“I think the best way is to go into a situation leaving yourself completely vulnerable. Don’t expect to go in there and write about anything the first time. Go in there and try to become these people’s friend. Try and figure out what they’re all about and let them figure out what you’re all about. Then when you know ’em, you can bring your notebook or your tape recorder… And then once you’ve finished, I think it’s very important to show them what you’ve done, and then continue to spend time with them, so they don’t feel that you were just down there exploiting them.”

Although he’s been compared to other maximalists like his friend David Foster Wallace and Thomas Pynchon, Vollmann is not shy about staking out the literary high ground:

“‘I hadn’t read Gravity’s Rainbow until after I’d written You Bright and Risen Angels,’ says Vollmann, ‘and I think that You Bright and Risen Angels is better… I guess I can see the comparison because Pynchon writes long books, the syntax is often involved, but I think that my style is a bit darker than Pynchon’s, I think my sentences are better, and I think that my characters are better.’”

In a bravura 1993 question-and-answer with Tom McIntyre for the San Francisco Examiner’s Image magazine (which duty compels me to note I was editing at the time), Vollmann offers serious reflections on his craft—“I’d like to continue to improve in my depiction of character’’—then turns the tables on McIntyre as the discussion turns to his fictional depiction of sex workers.

“Have you ever slept with a prostitute yourself, Tom?” he asks, turning away questions about speculation that he has other wives, in other countries: “I guess I’ll have to neither confirm or deny this rumor.’’

Talking with Steve Kettmann for Salon in the aftermath of 9/11, Vollmann is judicious about the feverish bin Laden hunt: “The way I look at it, he’s either guilty or he isn’t. If he’s not guilty, we’re definitely doing the wrong thing. If he is guilty, we should be fighting one person instead of a lot of bystanders who are going to take his side if they think he’s innocent.”

A 2004 session by Hemmingson for the San Diego Reader tests the always perilous boundaries between editor and writer; Vollmann is unhappy with the “Expelled From Eden’’ anthology title, catchy as it is, and objects to the possible inclusion of some personal materials.

The interviewer also deconstructs literary fanboyism:

“Of course, I, too, am eager to join Vollmann on his adventures, experience a bit of danger, hang out with questionable women, and foray into the unknown—all the things in his books that have made him a literary cult hero. I’m sure there are many who’d like to be in his company, who pester him about it like groupies to a rock star, so I’m hesitant to bother him. I know that writers need to be alone for their research and work. Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski, and Henry Miller (to name just three) were constantly hounded by fans who camped outside their homes thinking they could party with their idols and become part of their lives.”

Once under suspicion by the FBI under the ludicrous proposition that he might be the Unabomber, Vollmann is open about his politics, but aware of their limitations, telling Andrew Ervin: “I think that if you are called upon to do something that you can do, that will make a difference, you should do it even at the cost of your own life. I don’t think that you should romanticize what you can and can’t actually do.”

He amplifies the point with Donna Seaman for Bookforum: “Nabokov always used to say that any book that tried to teach him something, particularly some sort of political thing, he immediately banished from his bedside. And whether or not he wrote with feeling, I admire his work very much. Of course, he did end up writing in one way or another about dictatorship and exile. To read Nabokov is to think about some of the problems of totalitarianism and the Soviet Union and class privilege. So it’s always there.”

In 2004, in an interview with Lukes, he’s direct, with almost unfathomable detachment, about the health challenges he has faced: “Last week I had, basically, a minor stroke, and I’m fairly young for this to happen. And it was somewhat disturbing and upsetting, and at the same time, I have faced death before in my work, and so I’m basically recovered now, but if this were to happen again and finish me off, I think I’m ready. I think I have thought a lot about what I want to do, and I’m trying to do it, and fear is a very useful goad, it really is there to remind you: I don’t like what it is that I’m fearing: what do I like? What is it I want to be doing?”

Nevertheless, he persists—perhaps out of the conviction that this world of confusing sense-data and impressions is only one of many universes.

Tom McIntyre’s interview closes with a colloquy about one of Vollmann’s semi-fictional characters:

TM: It’s interesting that you used her in both “The Handcuff Manual” where she committed suicide in this allegorical story and yet, in other stories, she’s like a personal friend of yours. You used the same name. Is it the same character?

WV: Yeah, it’s the same character.

TM: Did Elaine Suicide commit suicide?

WV: Well, in one story she did and in another story she didn’t.

TM: In real life?

WV: There’s no such thing, Tom, as real life.

It’s just that conflation of the real and the fictional—sometimes heroic, sometimes self-mocking—that makes Vollmann’s voice so necessary in these seemingly dystopian times. Whatever the challenge, he’s here for it. And you.