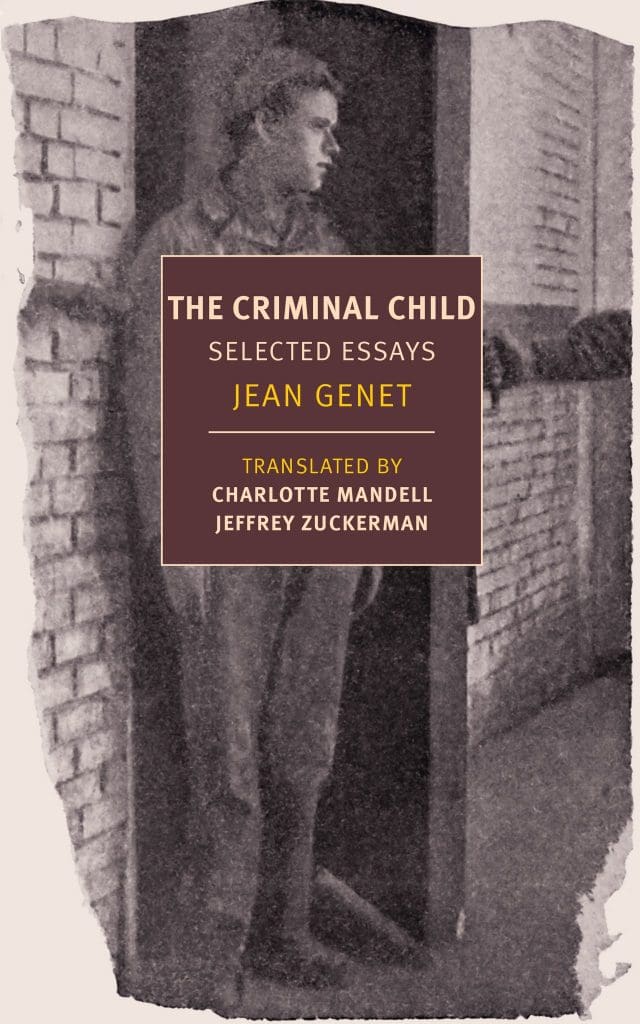

Born in Paris, novelist, poet, and dramatist Jean Genet grew up as a delinquent in state institutions, enduring the horrors of captivity only to later become a famous author and help revolutionize poetry and theatre. In The Criminal Child: Selected Essays (124 pages; NYRB Classics; translated by Charlotte Mandell and Jeffrey Zuckerman), a collection of Genet’s intimate and astounding essays on such themes as homosexuality, trauma, individuality, and the healing potential of creativity, we see how he chooses to view his past experience as a necessary evil on the path to becoming a great artist.

His beautiful, lyrical language is almost like poetry, and never fails to engage as he shares personal stories or observations on culture. In each essay, whether it be about reform school, his study of Alberto Giacometti, the ballet, Jean Cocteau, or tightrope walking, Genet embraces the unconventional and takes pride in his refusal to conform to societal norms.

In the titular essay, Genet expresses no judgment toward children found guilty of crimes. Instead, passion and empathy flows as he spends much of the piece exploring the reasons why children become delinquents. Abandoned by his mother when he was only seven months old, arrested for stealing by the time he was ten, and having spent the majority of his young adult years at the Mettray juvenile penal colony, Genet wants to be their voice:

A romantic fervor drives these children to crime; they project themselves into the most magnificent, daring, and ultimately dangerous lives. I am acting as their translator because they have the right to any language that will allow them to venture . . . where? I don’t know. Neither do they, however precise their fantasies, but it’s nowhere you’d call home. And I wonder if it isn’t perhaps vindictiveness that drives you to pursue them: because they scorn you, because they are leaving you behind.

I implore [criminal children] to feel no shame at what they’ve done and to safeguard the rebelliousness that has given them such beauty.

Though he does not encourage others to become criminals or resort to dangerous lifestyles, he cannot bring himself to regret his past, as it was his rebellious nature that contributed to his sense of individuality. He asks we see the beauty in our mistakes and how we can transform them into something greater.

Throughout these essays, Genet reveals a passionate love for the arts, transitioning from clear, direct prose to sublime lyricism to express his affection for his subjects, each of which, he believed, incentivized him to embrace a spirit of non-conformity. Solitude also played a role in shaping his sensibilities. (In fact, he repeats the word “solitude” quite often.) It’s clear that during his times of isolation, Genet was able to express his creativity and find a peaceful acceptance within himself. In his view, we should not fear or reject periods of loneliness; such moments can be a tool for self-discovery.

Granted, these essays are not meant to educate or persuade others to adopt certain behaviors. But in the final essay, “The Tightrope Walker,” Genet ends with, “It was a question of inflaming you, not teaching you.” His use of the word “inflaming” hints at the possibility of igniting an unknown desire from within. After finishing The Criminal Child, readers might be ignited, suddenly viewing their flaws differently, as inspiration to become something greater.