This Hasn’t Been a Very Magical Journey So Far (257 pages; Expat Press) is a difficult novel to categorize. It isn’t often that a crushing romantic tragedy unfurls in a universe so absurd. The book’s biting dialogue, irrational laws of physics, and buddy-comedy dynamic recall Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Beneath the story’s self-deprecating charm, however, lies a relationship that, in both its gentle initiation and passionate conclusion, raises questions about caring for one another and caring for oneself at the crossroads of love and mental illness.

This Hasn’t Been a Very Magical Journey So Far (257 pages; Expat Press) is a difficult novel to categorize. It isn’t often that a crushing romantic tragedy unfurls in a universe so absurd. The book’s biting dialogue, irrational laws of physics, and buddy-comedy dynamic recall Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Beneath the story’s self-deprecating charm, however, lies a relationship that, in both its gentle initiation and passionate conclusion, raises questions about caring for one another and caring for oneself at the crossroads of love and mental illness.

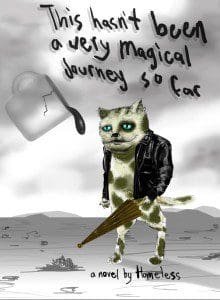

This Hasn’t Been a Very Magical Journey So Far is the first novel from poet and artist Homeless, who displays his work publicly on the streets and subways of New York City. At its center is Hank Williams, who has fallen in love with Patsy Cline, both characters endowed with the names of famed country musicians who died tragically young. Hank Williams leaves a mental hospital with the help of a man-sized cat clad in a leather jacket. The two embark on a destination-less journey as they grapple in tandem with the irreversible reality of romantic partnerships lost.

At times obscene and at others deeply emotional, This Hasn’t Been a Very Magical Journey So Far is a thoroughly surprising read. Homeless talked to ZYZZYVA about the novel.

ZYZZYVA: The characters in This Hasn’t Been a Very Magical Journey So Far range from people to cats to owls to gophers. What inspired you to blend the animal and the human?

Homeless: My initial idea when beginning This Hasn’t Been… was to write a children’s fiction book –– but for adults. To this day, I’m still a huge fan of Roald Dahl, especially James & the Giant Peach (which I give a nod to in my novel), so I wanted to do something like that. I wanted to have a story where a character goes on what’s supposed to be a magical journey with characters that are supposed to be magical. So combining human characters in a world with animal characters was just to give it that children’s fiction feel.

Z: The novel frequently jumps around in time, which I found very engaging. In writing the novel, did you work chronologically? What was your understanding of time within the world you created?

H: Honestly, I was all over the place when writing it. I had no idea where it was going, kind of like the way the characters have a destination in mind but they really have no idea where they’re going. I didn’t do that on purpose, but once I made that correlation I kind of let myself off the hook and just began writing these two separate storylines with no real end in sight. And so then I kept my eye open along the way for chances to connect them. It was an exciting way to write at times when it worked, but also insanely frustrating when it didn’t. I’d probably never it do it that way again.

Z: Reading the novel gave me the feeling of attempting to recall a dream—full of strange detail but often with vague chronology, boundaries, and stakes. Did you attempt in your prose to represent such a dream state –– or perhaps even psychosis?

H: While I don’t try to represent a dream state in all my prose, in this novel specifically I was aiming for a hysterical, fever-like dream, but one that was layered over a vague reality. In my head, Hank Williams actually goes on some kind of journey in the real world, but he’s so consumed with grief that he’s practically lost his mind, and so the way the book reads is how he perceives the world around him during this insanely troubling time in his life.

Z: I adored the romance at the novel’s core, and was both fascinated and frustrated with your depiction of the character Patsy Cline, who Hank Williams is mourning. At times she seems to exist only within Hank Williams’s sense of love and loss, but she can also be read as an autonomous character who makes decisions according to her own needs. Can you help me make sense of her?

H: I’m fascinated with people and characters who are in immense pain from simply being alive. People and characters who seemingly hurt for no reason. It’s like they don’t know how to exist on this planet, like every single moment of their life is a struggle. An example of a couple like that would be Sid and Nancy. And that’s where Patsy Cline came from — a Nancy Spungen type. The idea of this person who is out on control, and who knows they’re out of control, but can’t seem to navigate the pain of living. And people like that can be hard to make sense of. They do what they want to do. They live irrationally. They make drastic decisions. They seem to feel things stronger than most people –– but the appeal to that is, when you’re with them, you also feel things stronger, both good and bad, which is what Hank Williams experiences when he’s with Patsy Cline, and why he’s so desperate to find her after she leaves. I have no idea if I’ve answered your question, but…

Z: What drove your shift from the frank vignettes of your poetry to your first novel?

H: I wrote a novel because I needed to purge myself of a girl who had a hold on me. This book was really just a way of working through that. Poems can help, too, I guess, but only in smaller ways, in little bits and pieces. Whereas dedicating 200+ pages to this loss you’re going through really seems to allow you to work a lot more out. Even find some sense of closure.