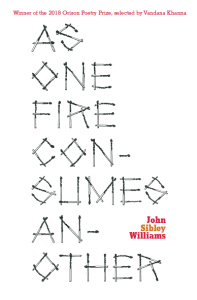

The poems in John Sibley Williams’ latest book, As One Fire Consumes Another (82 pages; Orison Books), are verbs: they implore and demand, they connect and recall, they cry out and they quietly walk away. The collection, winner of the 2018 of the Orison Poetry Prize, maintains a generational sense of story — an understanding of family that is dense in time and broad in scope as it considers both the immediacy of human relationships and the distance of the natural world. Williams is as acutely focused on the wide arcs of historical violence and injustice as he is on everyday detail, lending each poem a sermon-like quality.

The poems in John Sibley Williams’ latest book, As One Fire Consumes Another (82 pages; Orison Books), are verbs: they implore and demand, they connect and recall, they cry out and they quietly walk away. The collection, winner of the 2018 of the Orison Poetry Prize, maintains a generational sense of story — an understanding of family that is dense in time and broad in scope as it considers both the immediacy of human relationships and the distance of the natural world. Williams is as acutely focused on the wide arcs of historical violence and injustice as he is on everyday detail, lending each poem a sermon-like quality.

Williams’ meditations on some of life’s greatest questions take form as he relates honest perceptions of the world around him. There is a sense that the poet is exercising restraint — each poem is something like a paragraph, constrained within margins of identical width. The sentences themselves are spare, presenting each thought without superfluous explanation:

In the dark of a man’s fist pressed to chest.

Couch clothed in ghost-white sheets like a fishing village in winter.

Next time, use a Sharpie when listing your demands to god.

The collection reads as a sort of offering, inviting the reader to find connection and understanding where they might. And there is a sense throughout these poems that fragments form a whole –– in Williams’ frequently staccato use of language, and in his choices to revisit themes from multiple perspectives and leave visible his edits and revisions. Here are some choice examples:

To tell a body you are not my house, then to furnish it with walls & fire anyway

There is a breeze here that carries a hint of smoke from older crosses

Love feels out of context among so many dead & thirsting things.

What he heard reply from deep within the absence the night before he leapt, unbirdlike, isn’t much use to us now, the dead or the living.

In that last fragment, the seemingly despairing sentiment that often permeates this collection is tangible. But it’s not desperation but rather frankness that characterize Williams’ confrontations with death, loss, and communal pain. Moreover, the titles of the three series he divides the collection into –– Harm, Keeping the Old World Lit, and We Can Make a Home of It Still––suggest a possibility of rectification, or at the very least a forward momentum. Like the smoking aftermath of fire, Williams leaves room for renewal. His poetry itself is part of this project. The poem “Fallow as That” begins, We are out divining fish from dried riverbeds again. With this line Williams encapsulates every poet’s task, and in this collection he sets to work.