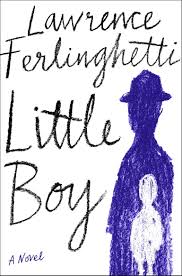

“And so do I return to the monologue of my life seen as an endless novel.” Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Little Boy (179 pages; Doubleday) is aptly self-identified as “unapologetically unclassifiable” on its jacket copy, and the poet Billy Collins called it a “torrent of consciousness” in his own review. Both descriptions are fitting for the short but powerful work by the now 100-year-old Ferlinghetti.

“And so do I return to the monologue of my life seen as an endless novel.” Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Little Boy (179 pages; Doubleday) is aptly self-identified as “unapologetically unclassifiable” on its jacket copy, and the poet Billy Collins called it a “torrent of consciousness” in his own review. Both descriptions are fitting for the short but powerful work by the now 100-year-old Ferlinghetti.

Little Boy begins as a rather fast-paced novel, narrated in the third person, based on Ferlinghetti’s childhood. It tells the story of Little Boy, who was raised by his Aunt Emily, later was moved to an orphanage, and then “adopted” by a wealthy but unaffectionate foster family of sorts. Just as readers settle into the story, the plot unspools into the lengthy monologue of a voice called “me-me-me.” “Me-me-me” becomes Ferlinghetti’s new central character as he transitions into the first person, and represents both Ferlinghetti and society at large, one riddled with narcissism and an obsession with the self. As Ferlinghetti abandons all punctuation and linear narrative structure, the writing reflects on the life he has lived and the world he was born into.

At times, the monologue seems circular as it returns again and again to the same few moments of his childhood, like the “cat’s eyes” tapioca pudding he remembers from the orphanage, or the bearded lover his aunt took when he was young. Among these recollections, readers are swept up in existential questions of agency, modernity, coming of age, and growing old:

I’ve summarized my past by theft and allusion and all I know is that I’ll be taking an escalator soon to the next level of existence or nonexistence and will it be the down-escalator or the up-escalator and thereby hangs the tail of this mutt and he still wagging it And how did he go from a youthful anarchism to humanitarian socialism as a creed to live by And how did he end up a painter and a poet always alienated in one way or another and still claiming that he was never ingested by the dominant culture that ingests so many rebels before they croak

Thoreau, Ginsburg, and other iconic writers are surely present, through both their influence and by reference, in Ferlinghetti’s meditations on the cultural shifts and stagnation he witnessed throughout the 20th century. He pays homage to his past by recounting his memories (he seems to remember everything) whenever they come to mind; it is almost as much a book about the 20th century as it is a book about Ferlinghetti. And since he believes the past informs the future, it is also a book about what is to come. In fewer than 200 pages, Ferlinghetti somehow touches on religion, capitalism, patriotism, sex, trauma, war, love, and more:

and what is the plot of this novel if not the remembrance of things still not past for the past is but a cautious counselor of what has yet to come what has yet to transpire or expire so farewell final albatross as time ticks on and all of us like insects in an anthill seen from space all nebulous figures dancing in a tropic night through the night-mazes singing a lyric escape again then and why not Are we to live in despair all the time thinking only of our certain deaths so why not live the highs and ignore the lows

Eventually, the “novel” settles back into full sentences and revisits the character it began with:

Little Boy grown up dissident romantic or romantic dissident has his youthful vision of living forever, immortal as every youth is, believing his own special identity would never, could never, perish.

Ferlinghetti’s Little Boy truly is a a deluge—not a stream—of thought that allows readers to witness the author as he grapples with the life he has led. It is a privilege to view the world—past, present, and even future—through his weathered, critical, and poetic lens.