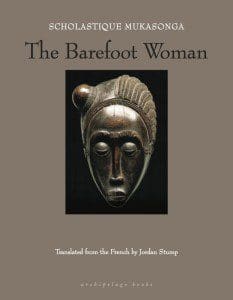

As a one-and-a-half-generation immigrant, I harbor a fair amount of nostalgia for a country I barely know—my native land of Kenya. Reading Scholastique Mukasonga’s memoir, The Barefoot Woman (146 pages; Archipelago Books; translated by Jordan Stump), heightened those feelings of nostalgia like nothing else even though the stories she tells are set in Nyamata, Rwanda. I suspect most Africans who read this book will have a similar response. Each chapter of the book contains a story or stories about Mukasonga’s family and their community of Tutsi refugees. We encounter them living in the aftermath of colonization and gradually embracing “progress,” which many perceive as adopting Western customs, while staying true to their traditions.

As a one-and-a-half-generation immigrant, I harbor a fair amount of nostalgia for a country I barely know—my native land of Kenya. Reading Scholastique Mukasonga’s memoir, The Barefoot Woman (146 pages; Archipelago Books; translated by Jordan Stump), heightened those feelings of nostalgia like nothing else even though the stories she tells are set in Nyamata, Rwanda. I suspect most Africans who read this book will have a similar response. Each chapter of the book contains a story or stories about Mukasonga’s family and their community of Tutsi refugees. We encounter them living in the aftermath of colonization and gradually embracing “progress,” which many perceive as adopting Western customs, while staying true to their traditions.

As charming and funny as these stories often are, they are tinged with a great sadness. We fall in love with Mukasonga’s mother, Stefania, and her community, particularly with the women who are the focus of this narrative, but we cannot forget the genocide on the horizon. Mukasonga keeps at the back of the reader’s mind the horror we know will claim the lives of these vivid, real-life characters—the Tutsis of Mukasonga’s community—whose lives grace the books’ pages. Above all, The Barefoot Woman is a fitting elegy from a daughter to her mother.

There’s a striking emphasis on community in the book. Life in Mukasonga’s childhood revolves around relationships bound by complex social rules that dictate etiquette, marriage, and gender roles. It is not that women have no power. On the contrary, the book is chock-full of powerhouse women, including Stefania, to whom many of the women in the village defer on matters of marriage; Suzanne, who is both scorned for her household’s slovenliness and respected because she plays the important role of giving the girls of the village their prenuptial examinations; and the stylish Kilimadame, a Rwandan woman who is notorious for having borne children by several different men and who is nicknamed “the-woman-of-the-white-people.” The business-savvy Kilimadame opens a shop that is famous for selling bread—a status symbol because it is considered a delicacy brought to Rwanda by white people—and is so successful that she is able to expand her shop into a “hotel” or bar.

Despite the power certain women wield in this community, nearly all of them must operate within traditional boundaries in order to secure husbands. However, to further underscore the agency of women in Mukasonga’s village, it is often the older women who orchestrate the girls’ or young women’s marriages. In a somewhat shocking anecdote, the women of the village trick an older, unmarried man into marrying a young woman who is in danger of becoming an “old maid.”

The narrator also recounts how she would spy on, and later report to her mother about, the young women who were seeking partners by looking them over as they bathed in the river, appraising them based on Rwandan beauty standards (which, at that time, were refreshingly healthy). According to Mukasonga, the girls and women of the village considered some of the following questions when assessing a girl’s beauty and suitability for marriage:

Did her manners and her nature bespeak a good upbringing? Was she a hard worker, unafraid to pick up a hoe? . . . . Did she walk with the grace of a cow, as the songs say? Did her eyes have the incomparable charm of a heifer’s? . . . . Could you hear the quiet rustle of her thighs rubbing together as she walked by? Did she have a delicate network of stretchmarks running over her legs?

Traditional rules not only circumscribed gender roles but also the interactions between women. In the chapter on “Women’s affairs,” a short walk home, for example, is made long by the requirement that Mukasonga and her mother stop and visit each hut on the way. (This is not the chore it would seem since gossip is also a means of finding out about potential dangers—in particular, any signs that the Hutu soldiers, who terrorize the community through plunder, rape, and murder, might be planning an attack.) Mukasonga writes:

That day, Mama might have stopped at Veronika’s house. Veronika was in no hurry to answer. Rwandan etiquette dictates that nothing be done in haste. Even if Veronika had been eagerly waiting for Stefania’s visit, it would have been unseemly to come running to meet her. First she began to make a little noise inside the hut, to show that she’d heard the visitor’s call; then, after a suitable delay, she slowly walked out to the junction of the path and the dirt road, where Mama was waiting. They embraced at length, squeezing each other’s backs and arms, murmuring words of welcome into each other’s ears.

Though this is a community in which many traditions are respected, we also find it grappling with which elements of European culture to embrace as “progress” and which to reject in favor of the old ways. In one example, the community is scandalized when a young woman named Félicité “convince[s] her father to build a little house just for her.” Mukasonga writes:

A girl who wasn’t married—who, if she went on following the weird ideas of the white people, might never marry at all—living alone, sleeping alone, without her sisters, yes without her sisters. People found it shocking, an affront to all our traditions, wanting to sleep alone when she had so many little sisters who naturally had a place beside her on the mat.

What’s more, Félicité even has her father build her an adjoining, smaller house. The village is perplexed and wonders what purpose this smaller house might serve. When they learn what it is—a latrine—they quickly adopt this innovation. “Women talked their husbands into digging new trenches so they could install the same facilities as Marie-Thérèse [the young woman’s mother]. It was progress, amajyambere!” This humorous story takes an unexpected and tragic turn in the next sentence when Mukasonga laments, “How could they have known that many of them were digging their own graves?”

There are numerous twists like this one. You are enjoying a well-written anecdote, laughing out loud in one sentence, only to be quieted by the next sentence. This speaks to Mukasonga’s prowess as a storyteller. More importantly, it causes the reader to reflect on how it might have been for so many of the people in this narrative—the people whose names Mukasonga writes and repeats with reverence—to, all of a sudden, disappear.

The short biography on the back of the book states that Mukasonga lost thirty-seven of her relatives in the 1994 genocide. In 2007–2008, the specter of genocide appeared in Kenya though, as in Rwanda, it had been festering for decades through divisions rooted in the eugenics-based hierarchical categorizations that white colonizers had imposed on various African tribes as part of their “divide-and-rule” strategy—categorizations that socioeconomically elevated some tribes over others. As Mukasonga writes of her community:

The white people had unleashed all the insatiable monsters of nightmares on the Tutsis. They held up the distorting mirrors of their untruths, and in the name of their science and their religion, we were made to see ourselves …

The white people claimed to know better than us who we were, where we came from. They’d examined us, they’d weighed us, they’d measured us. Their conclusions were final…

According to Al-Jazeera’s James Brownsell, approximately 1,400 people were murdered by members of warring tribes in Kenya’s post-election violence in 2007–2008. Since then, the community of Kenyan-Americans of various tribes that I was raised in has fallen apart. And when I meet a Kenyan, even here in the States, I can often tell that she or he is attempting to figure out my tribal affiliation: whether I am friend or foe.

During the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, approximately 800,000 people, most of whom were Tutsi, were massacred. To put this in perspective, more than 70 percent of the Tutsi population in Rwanda was wiped out. (An estimated 30 percent of the indigenous, minority Batwa community was also eradicated.) Since then, Rwanda has undertaken the monumental task of reconciliation, which, by most accounts, has been largely successful. However, one of the great lessons of The Barefoot Woman is that we must never forget what happened in Rwanda. Mukasonga is right to not let us.