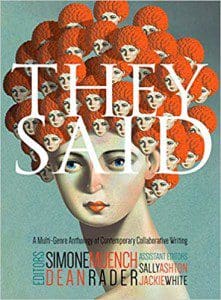

They Said: A Multi-Genre Anthology of Contemporary Collaborative Writing (535 pages; Black Lawrence Press), edited by Simone Muench and Dean Rader, is an ambitious, immersive collection that challenges readers and writers alike. Breaking out of traditional ideas of authorship, the book gathers hundreds of pieces of multi-author writing that span multiple genres and formats. At the end of each work is a blurb written by the authors that describes their unique writing process. In the spirit of the collection, we decided to collaboratively read and review the work in the form of a conversation.

They Said: A Multi-Genre Anthology of Contemporary Collaborative Writing (535 pages; Black Lawrence Press), edited by Simone Muench and Dean Rader, is an ambitious, immersive collection that challenges readers and writers alike. Breaking out of traditional ideas of authorship, the book gathers hundreds of pieces of multi-author writing that span multiple genres and formats. At the end of each work is a blurb written by the authors that describes their unique writing process. In the spirit of the collection, we decided to collaboratively read and review the work in the form of a conversation.

Claire Ogilvie: What stood out most to me about this anthology was the conscious noting of the authors’ writing processes and unintentional similarities of those processes across genres. It was interesting to see that many of the works started off as passion projects, or as a joke between friends, and then morphed into something more meaningful that was later published or performed. Some of the contributors, following the styles of their work, described their writing process similarly, like Maureen Alsop and Hillary Gravendyk who poetically note of their piece “Ballast”: “A mirror shone a refused language, the last moon slipped. As to the dreaming craft lightened one moment then another left.” While I didn’t exactly grasp what this described of their process, it did help me better understand the authors’ thoughts and intentions.

Caleigh Stephens: All of the writing about process definitely adds this extra dimension. I found the writing, and the writing about the writing, to be conversational, which helped illuminate the relationship between the authors outside of the piece. Creative writing is often presented as this isolated and individual art, and They Said functions as a challenge to that. The nature of collaborative writing is that it allows the author, as John F. Buckley and Martin Ott note, to “get out of that ‘I’ voice, that sometimes dark, sometimes limiting well of ego.” There’s a focus on process that underlies the entire collection, and while there are many excellent pieces of writing here, the anthology fundamentally is a work for writers and people fascinated by the craft of writing.

CO: I agree that the informal, candid description of processes enhances the work since it gives more background about the authors themselves and their relationship, or the concept of what they set out to write originally, as well as the often unexpected results. The series of poems that features the “The Sea Witch” by Sarah Blake and Kimberly Quiogue Andrews has one of my favorite process notes because, while some of their poems about the Sea Witch are a little cheeky or even slightly humorous (“The Sea Witch Needs a Mortgage for The Land, If Not for The House of Bones”), the poems had an overall experimental nature that the authors explained as “…a bit like a very friendly tennis match wherein one of us starts by making the ball. One of us will write a draft of a poem, as complete as we can get it, and then we send it to the other, who has free reign to add, cut, rearrange, etc.” Blake and Andrews process was clearly one of friendship and trust, which is reflected in their work.

CS: I also found “The Sea Witch” poems to be interesting due to the range of style and tone. With such an intricate and individual art such as poetry, the meshing of two (or more) voices cultivates an atmosphere of exploration. Some authors choose to write back and forth while others merge into a singular voice, becoming indistinguishable. Some, like the cross-genre piece “The Wide Road” by past ZYZZYVA contributors Carla Harryman and Lyn Hejinian, include both—writing that hovers between poetry and prose, followed by letters written by the authors that are “about our work-in-progress as a part of the work itself.” The collaboration is embedded into the text rather than being something the authors must work around. “The Wide Road” also stands as an example of the experimentation that pervades the collection. Even beyond those pieces labeled “cross-genre,” there’s an interplay of poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction throughout that results in writing that flouts convention.

CO: It all sort of feels cross-genre to me, like some of the fiction could have just as easily fallen into another category. Like Tina Jenkins Bell, Janice Tuck Lively, and Felicia Madlock’s piece, “Looking for the Good Boy Yummy,” which takes the real events of Robert “Yummy” Sandifer’s life and final moments and then fictionalizes them through multiple perspectives and narratives. In their description of their process, they write, “We chose to tell Yummy’s story in the form of a hybrid comprised of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry because so much has been said about him and each form would reflect a different view. We believed the true Yummy was somewhere in the center of all the accounts.” The authors are intentional about mixing genres to better represent the realities of gang violence and poverty. The fictionalization of the story takes it to an interesting, murky, and political place. Which raises the question: when does a fictionalized account become cross-genre?

CS: The beauty of the collection is that although each section is labeled by genre, the works are able to move beyond those confines and tell their stories in the most authentic way possible. Thanks to the collaborative aspect, not in spite of it, the writers feel free to challenge themselves stylistically. Some pieces came out of literary games –– authors adding two sentences at a time or working in “antonymic translation.” On the whole, the stakes don’t feel very high in those examples, and often the works aren’t perfect, but this doesn’t lessen the anthology’s ultimate impact. As Cynthia Arrieu-King and Ariana-Sophia Kartsonis write, “We play and I still feel astonished by what happens when we do.” This is an inspiring collection precisely because it brings up more questions about the nature of writing than it answers.

CO: Yes, the most impressive aspect of this anthology is its commitment to collaboration –– from the editing, to the writing of the introduction, the collaborative reviews of the material inside, and the pieces themselves. It’s collaboration within collaboration, and even if a piece didn’t necessarily resonate with me I always respected the craft of the poem, or story, or genre-breaking-rule-defying piece in front of me. It’s all so thoughtful and intricate. You can tell from the effort shown by the contributors and the editors that it’s a labor of love, and as a writer and reader that’s what interests me.

Caleigh Stephens and Claire Ogilvie on their process: Claire and Caleigh originally (and quite candidly) had no idea how to go about writing a collaborative review of a collaborative anthology. The entire review-writing process was an extended conversation, as they picked out individual sentences and pieces to share with the other while reading.They came to appreciate the art of “collaborative writing” all the more after giving it an honest attempt one Sunday afternoon. Distracted by IKEA locations, yerba mate, and the current state of U.S. politics, they holed up in Claire’s living room and decided that they wanted their review to reflect the ongoing dialogue they had about the work. In short they would describe their own artistic collaborative process as “in cahoots.”