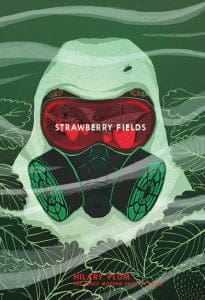

Strawberry Fields (Fence Books; 224 pages), the breathtaking new novel from Hilary Plum, and winner of the Fence Modern Prize in Prose, opens with what might be the common denominator in humanitarian crises around the world: a nameless American at a refugee camp in a nameless country. “The children’s suffering has been unimaginable,” the American begins—as if we did not already know this.

Strawberry Fields (Fence Books; 224 pages), the breathtaking new novel from Hilary Plum, and winner of the Fence Modern Prize in Prose, opens with what might be the common denominator in humanitarian crises around the world: a nameless American at a refugee camp in a nameless country. “The children’s suffering has been unimaginable,” the American begins—as if we did not already know this.

But soon, one of the children is telling the gathered reporters and NGO representatives at the camp what he learned in school: the towns of his country, the names of its leaders, even the locations of rebel supply camps. “Who is your teacher?” the reporters ask, “is she still alive?” The child does not respond. A camp administrator shakes her head. “You don’t think he made her up,” the Swedish journalist says to her, aside. “No,” the administrator says, “but children are easy to fool.”

Within this short scene Strawberry Fields opens its focus, which is not children but adults—namely, journalists, and the virulent scenes of their information. Each three-to-ten-page chapter takes the perspective of a different person reporting on or investigating or sometimes even participating in some event around the world, from the torture of prisoners of war to the calm interior of an eating-disorder clinic. Many of the scenes are tragic, some viscerally so, but none feel out of place. Together they form one of the most astonishing reading experiences to be had in recent years.

Everywhere this book seethes with feeling, with guilt, agony, righteousness, and shame. Many of the reporter-narrators display a Didion-like emotional hardness, but just as many suffer an intense and visible motivation for their work. Each is also, without exception, fully rounded: Plum has an incredible way with characterization and wrings from each chapter a discrete narrator whose experiences we accept not as links in a long chain, but rather more like pieces of color in a brilliant collage. This is partly due to the constantly shifting angle of presentation. One chapter may have someone viewing a video of a car bomb and trying to determine whether or not it is real, while another may be told in a bare-bones Q&A format. Some narrators speak directly to the reader, mourning the death of a friend or sibling; others hide thin as paper behind their subjects, their very questions erased from the page.

The only recurring plot line revolves around a reporter named Alice, who is investigating the apparently random shooting of five veterans who were participants in a PTSD program. (Every other chapter is hers, although they are just as short as the others, and do not necessarily stay in a single timeline.) A detective named Modigliani is investigating the deaths as well. Alice and Modigliani have known one another from the sites of other murders, natural and humanitarian disasters, and their affectless conversations bear traces of a ravaged hardness and pain. It is one of the more delicate questions of the novel: what kind of feeling can be forged over such work, and what is the relation that develops so far outside of friendship or love?

The most immediate issue that Strawberry Fields contends with, however, is our longstanding familiarity with catastrophe, whether received through breaking news or investigative journalism. It is the latest in a long line of attempts to whack us on the head and break our glazed expression: not a call to action, exactly, but an appeal to both reconstruct our forces of empathy and maintain a never-ceasing critical perspective.

Unfortunately, at this point, even the idea of defamiliarization has become familiar. Take, for example, Alfredo Jaar’s 2006 installation The Sound of Silence, which forces a handful of viewers into a small black cube, where a slow and quiet slideshow tells the life of photojournalist Kevin Carter one sentence at a time. Carter’s best-known work is a photograph of a starving Sudanese boy with a vulture in the background, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1994. Three months after receiving the award, Carter killed himself, citing oppressive memories of corpses and pain. When the slideshow reaches this point in Carter’s life story, after five or six minutes of single lines of text going in and out of the dark, it gives off an immense white flash, after which the photograph is slowly revealed.

Images of trauma and horror still play an important role in news coverage, especially where children are involved, but today we are much more likely to read about an event on a device than watch images play out on a large screen. The 2017 Pew Report shows readers moving away from televised news toward digital articles at an increasingly fast pace, especially in younger demographics, and while our complicity in the normalization of tragedy remains a highly relevant issue, it is one that, I would argue, has been submerged into the medium of prose, where it is more difficult to detect and understand.

So does Strawberry Fields succeed in destabilizing our relationship with text journalism? The jacket copy certainly declares it “an antidote to normalization.” But the book is fictional: our empathy is neither demanded nor especially useful. Surely we are better off reading the nonfiction from which Plum gathered her inspiration, the books of authors like Robert Fisk or Jeremy Scahill, or at the very least remaining vigilant readers of The Nation and The Guardian. After all, with so many of the details left out—place names, job titles, policy directives—how can we expect Strawberry Fields to enforce a change in the way we perceive events? As The New York Times has reminded us recently, with all the annoying self-righteousness of an editor-in-chief at a high school newspaper: The Truth Matters.

More than forty years ago, Fredric Jameson asked if the ideals of good news writing—namely, clarity and simplicity of prose—might not be serving a different purpose than the mere distillation of important information. “What if,” he asked, “they were intended to speed the reader across a sentence in such a way that he can salute a readymade idea effortlessly in passing?” He wrote this at a time when some of the most novel forms of journalism were being produced, which says something about the sheer obstinacy of mass media coverage. Today, it could not be plainer that Jameson was correct to ask such a question. Rapidly increasing news biases, metacritical “exposes” and good old-fashioned handwringing in the news industry shows an increasing awareness all around that it is not enough to simply write or read for The Truth. It is no wonder that fiction continues to tackle such issues so eagerly.

But why, precisely, does Strawberry Fields succeed where other novels and projects have failed? Because it does succeed—excessively so. Partly it’s because of Plum’s impressive ability as a writer. Even her occasional awkward sentence seems like something intended to disrupt our all-too-quick perception of subject and object: “Above us the sky the shells traverse does not reveal them: death so quick you see only its shadow.”

The real reason Strawberry Fields succeeds, however, is that it speaks to the recent shifts in how we read. We read news at all hours of day and night, articles scattered across many different outlets, with subjects varying from political to scientific to downright stupid, taking in journalism with all the discrimination of a dog lazily gobbling up scraps of turkey by the fireside. Strawberry Fields evokes this bloated and dreamy news intake in an unprecedented manner. Its range of reference spans the Irish Civil War to the assassination of Osama bin Laden, but nothing is wholly determinate, which means some surely invented chapters have the feeling of actual events. The title chapter, in which an aging reporter covers the outbreak of a deadly toxin in a strawberry field, elicits memories of a huge number of similar articles, like the poisonous drying of Southern California’s lakes, the first major outbreaks of Ebola, or even the events at Standing Rock. It is incredible how much detail the mind will project onto the barest of proper nouns: a British-sounding street, an Arabic name. (At one point I found myself congratulating Plum on her nuanced take on Hurricane Maria, before realizing that such a recent event would not have likely made it in a book published in April.)

All this is to say that Strawberry Fields is postmodern in the best sense of the word. Some experimental fictions can feel, on days when we are perhaps least forgiving of current events, just irrelevant in their airy spheres of language, but Plum fragments her writing to bring in the rest of the world. A line that would be a clichéd nearly anywhere else—“My dreams could have been called nightmares were they not made up of memories”—brings tears. A chapter combining actual apologies offered by American and British officials in response to Abu Ghraib, along with statements made by former prisoners at Guantanamo—mixing them together in a single voice, sometimes even in a single sentence—makes perfect sense. Strawberry Fields exerts power. It takes this literary trend, the transposition of news into fiction, and delivers it with sufficient force to finally meet growing demand. It should not be ignored.